When trash becomes a universe

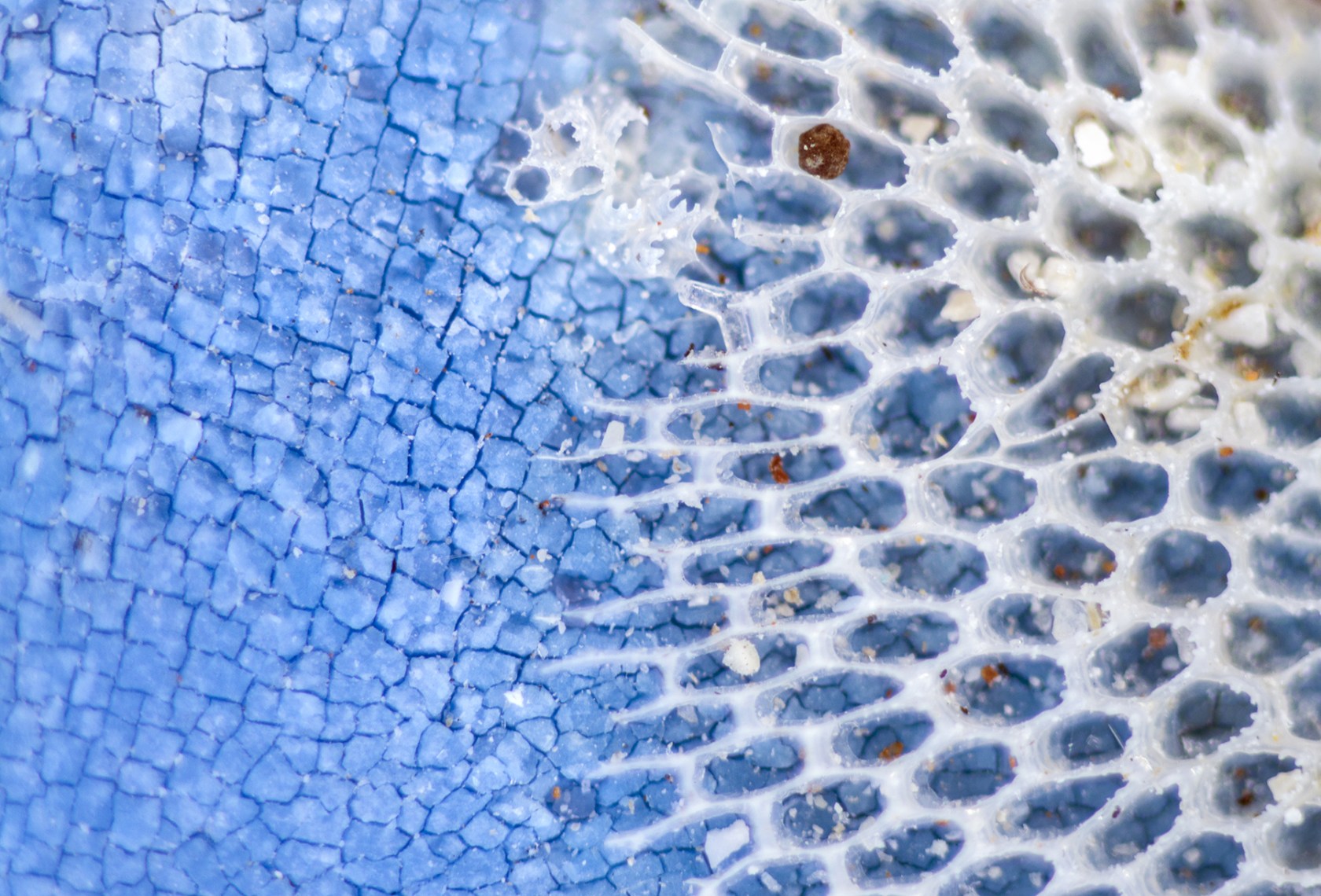

Bottle caps found on the Australian coast.

© TRES [ilana boltvinik + rodrigo viñas], photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard staff

Artist collective brings ‘intraterrestrial’ worlds to Peabody Museum

The bottle caps washed up along the beaches of Australia looking almost like miniature planets. Some looked like flat, hard planets made of marble; others looked watery and remarkably like Earth. Many of them had been colonized and transformed by aquatic invertebrates called bryozoans.

The peculiar sea trash caught the imagination of the art collective TRES and formed the backbone of their exhibit, “Castaway: The Afterlife of Plastic,” now on display at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology. Over a 2½-month road trip in a Toyota camper van, the Mexico City-based duo Ilana Boltvinik and Rodrigo Viñas photographed the bottle caps — as well as soda cans, shoe leather, plastic doll parts, deodorant containers, and rubber gloves — they found washed up along the Australian coast.

“Even our debris has become a platform for other types of life.”

– Ilana Boltvinik

TRES is not new to finding beauty in what others might overlook: Previous projects have featured used chewing gum scraped off the streets of Mexico City, cigarette butts, and even found bottles full of urine. “One of our main concerns is to try to offer a different perspective on trash,” said Viñas. “We’re proposing a more intimate relationship with our residues.”

The inspiration for “Castaway” came during a previous project, “Ubiquitous Trash,” which collected and examined trash collected in Hong Kong. They found bottle caps printed with the image of the Hong Kong actor and celebrity chef Nicholas Tse, but that type of bottle was only available in mainland China, Boltvinik said.

“One of the questions we had at the beginning, because we like following the traces of things, was, ‘OK, this is the bottle cap, where is the rest of the bottle?’ They’re probably at the bottom of the ocean. That made us think of bottle caps as the tips of icebergs that are a small part of a very large story.”

Calcium deposits are visible in this bottle cap in “From the Future to the Present.”

© TRES [iIana boltvinik + rodrigo viñas]

The pair expected to find beautiful bottle caps on their Australian road trip, but they were surprised by the strange, coral-like substance they found growing on and inside them. The substance sometimes carved holes in the plastic or turned its surface into entirely new shapes and textures that looked like the surfaces of alien worlds. They consulted Paul Taylor, an invertebrate paleontologist and bryozoologist at the Natural History Museum in London, who identified the growths as the calcium deposits of jellyella eburnea, a species in the phylum Bryozoa.

Bryozoans are microscopic invertebrates that work together to build the elaborate calcium-based structures that TRES encountered. Bryozoans are known for the division of labor within their colonies. Some of them filter water; others specialize in reproduction; still others construct their homes.

“It’s another universe, it’s amazing,” Boltvinik said.

Trees in Yallingup Beach, Western Australia, resemble found rope in “Parallel Lives I.”

© TRES [ilana boltvinik + rodrigo viñas]

Found plastic rope resembles a tree in Yallingup Beach, Western Australia, in “Parallel Lives II.”

© TRES [ilana boltvinik + rodrigo viñas]

The exhibit invites viewers to break down the barriers between natural and unnatural, valuable and disposable, good and bad. After all, plastic has become new home worlds for an “intraterrestrial” life form, as TRES put it, and that life form has terraformed those worlds in its image.

The exhibit is the result of the Robert Gardner Fellowship in Photography, a Peabody Museum effort that funds established artists to create and publish a major work of photography “on the human condition anywhere in the world.” TRES received the fellowship in 2016.

Ilisa Barbash, curator of visual anthropology at the Peabody Museum and the curator of “Castaway,” said the pieces raise a question that often comes up in her field.

“It’s always a problem in anthropology, the aesthetics, especially when you’re dealing with difficult topics — trauma or war or garbage. What if the pictures are beautiful?”

“Intraterrestial Aliens: Forgotten Smell.”

© TRES [ilana boltvinik + rodrigo viñas]

“Things in a Forgotten Map I.”

© TRES [ilana boltvinik + rodrigo viñas]

The exhibition also draws connections to Harvard’s scientific history. Alexander Agassiz, son of Louis Agassiz, who founded Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, led expeditions to Australia in the same region that TRES explored. The Peabody Museum collaborated with the Museum of Comparative Zoology’s Ernst Mayr Library to include actual jellyella eburnea structures from Australia in the exhibit.

“We are not in control of everything,” Boltvinik said. “Even our debris has become a platform for other types of life. It’s not that it was ever designed for something like that, but the world is bigger than humans, and things that happen in the world are bigger than humans.”

Ilana Boltvinik (left) and Rodrigo Viñas.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Castaway: The Afterlife of Plastic” is on display through April 6 at the Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology.