‘The Odyssey’ is having a moment. Again.

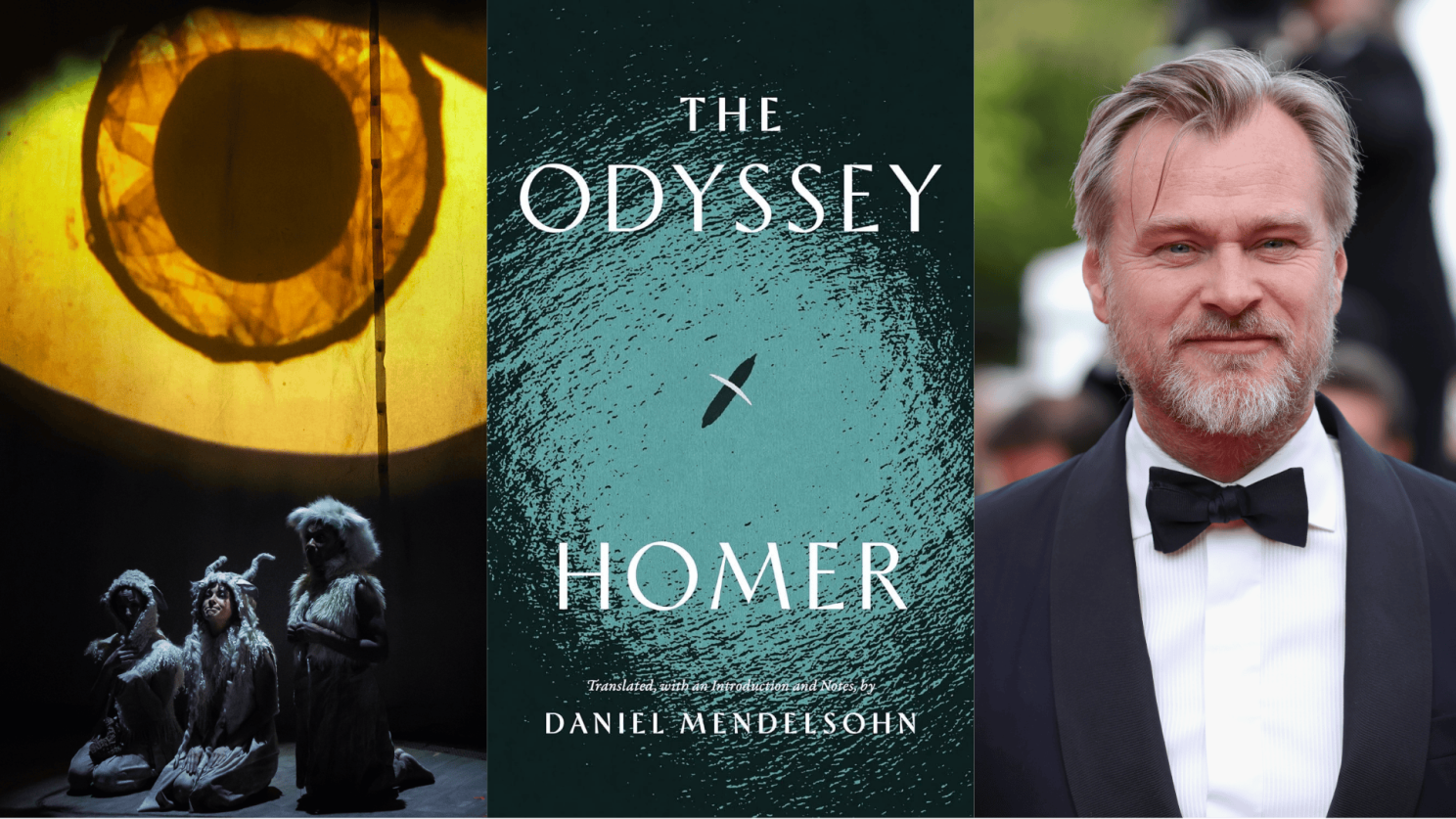

The enduring appeal of the “The Odyssey” can be seen in the A.R.T.’s production; a new translation by Daniel Mendelsohn; and a forthcoming movie from director Christopher Nolan (pictured).

Photos by Nile Scott Studio and Maggie Hall; Andreas Rentz/Getty Images

Classicist Greg Nagy on story’s epic appeal, his favorite translation, and ‘journey of the soul’ that awaits new readers

Homer’s “Odyssey” has captured people’s imaginations for nearly 3,000 years. Testaments to its enduring appeal abound: A recent stage adaptation of the epic poem at the American Repertory Theater; a movie by Oscar-winning director Christopher Nolan is in the works; and a new translation by Bard scholar Daniel Mendelsohn will be published next month.

In this edited interview, Greg Nagy, Francis Jones Professor of Classical Greek Literature and Professor of Comparative Literature, reveals his favorite of the more than 100 translations of the poem, explains the appeal of the “trickster” Odysseus, and more.

What can you tell us about Homer?

There is nothing historical about the person called Homer. However, there’s everything historical about how people who listened to Homeric poetry imagined the poet. Homeric poetry evolved especially in two phases. The earlier phase was in coastal Asia Minor, in territory that now belongs to the modern state of Turkey and in outlying islands that now belong to the modern state of Greece. In these areas, around the late eighth and early seventh centuries B.C.E., there was a confederation of 12 Greek Ionian cities, which is where “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” evolved into the general shape that we have. A second phase took place in preclassical and classical Athens, around the sixth and fifth centuries B.C.E. Before such a later phase, almost anything that was epic could be attributed to this mythologized figure called Homer.

Gregory Nagy.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

There have been more than 100 translations of the poem. Do you have a favorite?

I like the translation by George Chapman, a poet in his own right, who published the first complete translation of “The Odyssey” into English in 1616. There is that famous poem by John Keats (1816), in which he speaks about reading Chapman’s Homer. I also like the translation by Emily Wilson, who was the first female translator of “The Odyssey” (2017) into English.

I also like the translations by Richmond Lattimore and Robert Fitzgerald, both of whom were dear friends. Lattimore was probably one of the most accurate translators of Homeric poetry; he cared about the original Greek text as it was eventually transmitted. He is easy on the eye, but hard on the ear. Fitzgerald is easier on the ear. And then there is Robert Fagles (1996), who has done the most actor-friendly translation.

I like Wilson’s translation very much. She is a great poet; she has a real ear for what’s going on in the minds and hearts of the characters. One of my favorite parts is how Wilson handles the gruesome death of the handmaidens who are not loyal to the household of Odysseus, and their agonizing death is so beautifully treated without any false sympathy.

Novelist Samuel Butler, who was a real romantic of the Victorian sort, wrote the book “The Authoress of ‘The Odyssey,’” where he imagines that the poem is composed not by Homer, but by Homer’s daughter. For her masterful translation, I would say that Wilson could be considered as the daughter of Homer.

Why do we find Odysseus fascinating? He’s cunning, vengeful, and so flawed …

I learned when I was a graduate student at Harvard from my professor, John H. Finley, that Odysseus, whom we all see as an epic hero, gets “a bad press” almost everywhere except in “The Odyssey.” Odysseus is what anthropologists call a trickster — a hero who is not originally an epic hero, but someone who, by way of knowing all the norms of society, can violate every rule, whether it’s a deeply ingrained moral law or whether it’s a matter of etiquette, as in the case of table manners. The value of the trickster is that it teaches us what the rules are because the trickster will show you how every one of them can be violated.

“The value of the trickster is that it teaches us what the rules are because the trickster will show you how every one of them can be violated.”

What we read in the very first line of “The Odyssey” summarizes it: “The man, sing him to me, O Muse, that man of twists and turns …” What can be more fascinating than somebody who has unlimited capacity to shift identities?

Who is your favorite character? Odysseus? Penelope? Telemachus?

Penelope is my favorite character in “The Odyssey” because she’s so smart. I have written a commentary interpreting the dream of Penelope that she narrates to her husband, who is still in disguise. If my interpretation is right, then the deftness of her narration shows that she is even smarter than Odysseus!

Finally, what should readers learn from the poem?

In the Homeric “Odyssey,” the hero experiences a journey of the soul. Reading the epic can lead to the reader’s own journey.