File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

More than kind of blue

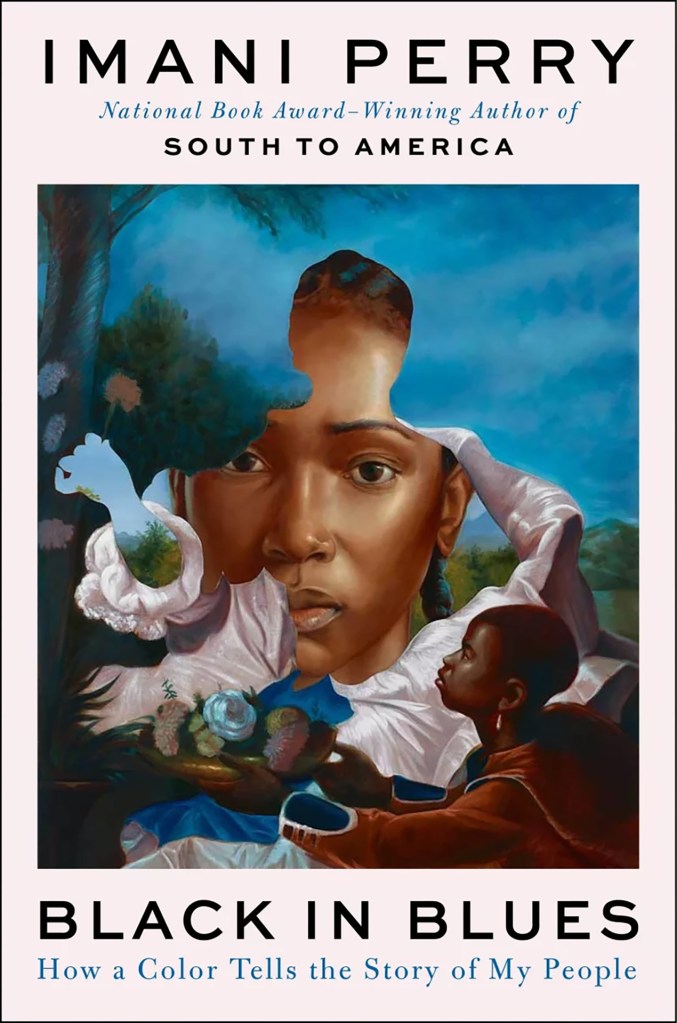

Imani Perry’s lyrical new book weaves memoir, history to consider central place of a color in Black America

Imani Perry often slept in her grandmother’s bedroom as a child. The walls were grayish, a tile missing in the ceiling, which had been dropped to save on heat. Through that gap, she could see the room’s original color, a bright blue “like the sky in August.”

In her latest book, “Black in Blues,” the National Book Award-winning author reimagines the gap as a “portal” to consider the significance of the vibrant color within Black history and culture. Perry weaves memoir and history to consider shades of blue from Africa, across the Atlantic, and to the Americas through the eyes of the Black diaspora.

The Gazette spoke with Perry, the Henry A. Morss Jr. and Elisabeth W. Morss Professor of Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality and of African and African American Studies, and Carol K. Pforzheimer Professor at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute, about her new book, the first since her 2022 bestseller “South to America.” This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What was the writing process like for “Black in Blues”?

I was really inspired by African American artist Romare Bearden. There’s this article where music critic and novelist Albert Murray describes Romare Bearden’s process of making collages. You look at the painting, and you see an image of something, but each of the pieces he’s cut out are in and of themselves art pieces.

Trying to put them all together to make a picture in a way that coheres or that makes sense was, for Bearden, the way that the aesthetics of [classical jazz] made their way into his visual work. For me, that’s how both make their way into my written work. Trying to get that compositional piece that I am so inspired by both visual arts and music.

The book reads as both a memoir and a lesson in Black history and culture. Why was it so important for you to weave in your personal experiences and connections to the color blue into this project?

Much of what I was sensing my way toward — and I mean sensing on not just an emotional level, but an emotional, intellectual, and spiritual level — was rooted in experiences and encounters with blue. So, that piece was important.

The relationship I felt to blue that came about as a result of sleeping in my grandmother’s bedroom was important. In some ways, I treat this missing tile and her ceiling as the portal that becomes this pathway for me to think about — not just why it produced this feeling and why I was seeing all these things, but then figuring out how to tell a story about that.

Your book underscores the fact that blue is often written about and explored by Black writers, scholars, and artists. Why do you think that is?

On one level, it’s because of the universality of blue. That is to say, blue is cherished the world over, and you can find references to blue in every tradition.

There’s something, in particular, that takes shape in Black life that is a result of the reality of the transatlantic slave trade and our relationship to ports. These were places that were nurturing and of worship and reflection that become places of devastation. That is part of why I say that Black life is a water epic. That crossroad of the site of the disaster, but also these places where people continuously go to have kind of spiritual encounters.

I try to make clear at the beginning of the book this idea of Black people as relatively new in human history. People were all these other things. It is a concept that comes about through empire and the disasters of empire, but people make something meaningful of it.

That also has to do with the color blue. I think that’s why the music became known as blues music. Blue is contrapuntal. It’s both a color of sorrow and joy. It’s the color of the water as terror, but also as possibility.

“Blue is contrapuntal. It’s both a color of sorrow and joy. It’s the color of the water as terror, but also as possibility.”

Early on in “Black in Blues” you write: “Black was a hard-earned love. But through it all, the blue blues — the certainly of the brilliant sky, deep water, and melancholy — have never left us … the blue in Black is nothing less than truth before trope. Everybody loves blue. It is human as can be. But everybody doesn’t love Black — many have hated it — and that is inhumane.” Can you delve into that powerful passage?

At the core I want to make clear that there’s this color that captivates people because it’s a universal human experience. We see the waters, and we see the sky. And it does this work upon us.

Then you have this categorization of human beings that’s meant as degradation and insult. But because we are human, we make something meaningful — even out of that condition — and create culture and art. All of these things are at once an insistence upon the fullness of the humanity of Black people and also an engagement with this universally captivating color.

You later discuss the revival of the blues and the renaissance of writing by Black women in the 1970s and 1980s. Why do you feel like this was such a distinct period for the color, sound, and artistry of blue?

In a sense, the mainstream Civil Rights Movement is an olive branch. It’s an insistence upon rights, but it’s also an olive branch to the larger society, from Black Americans, that is met with some legal gains, but also in many instances, with hostility, whether it’s white flight or the backlash against civil rights. Then there’s a moment of turning inward in Black communities. There’s this extraordinary bubbling up of artistic production.

For Black women, this also becomes particularly important, because we had the women’s movement, the beginnings of the gay rights movement, as well as Black Power. All these movements are people who have been on the margins, finding voice and space.

In this combination of the power of the freedom, you get this beautiful outpouring of creative production and access to mainstream publishing houses for the first time. For me, that work was being made literally as I was coming of age. I was born in 1972 and all of that work of the ’70s was all around me. It was an inheritance that I feel very passionate about.

What are you hoping readers take away from this latest project?

I always think of my books as artifacts, and I hope people find them interesting and pleasurable, or at least moving. But more than anything, I think of them as offerings that are companion pieces to living and to other work. I hope my readers will read a passage and then they’ll go out in the world, and something will resonate in the way that they encounter blue, and it will spur ideas, or become somehow nurturing, healing, or inspiring.

With all of my books — and my work in the classroom — I’m always both standing in a tradition and in a conversation. I’m always sort of trying to emphasize these threads of connection with other people, present and past and future. I want to make an invitation to the people who read the book to be in conversation with me.