Study authors Brennan Klein (from left) and Elizabeth Hinton with Brandon Terry, co-director of the Institute on Policing, Incarceration & Public Safety.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

COVID prison releases expose key driver of racial inequity

As incarcerated population dropped overall, proportion of Black prisoners rose. Researchers point to unequal sentencing.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. experienced a historic reduction in prison population as admissions declined and many incarcerated people were released — both routinely and as part of state and federal public health strategies to decrease spread of the virus.

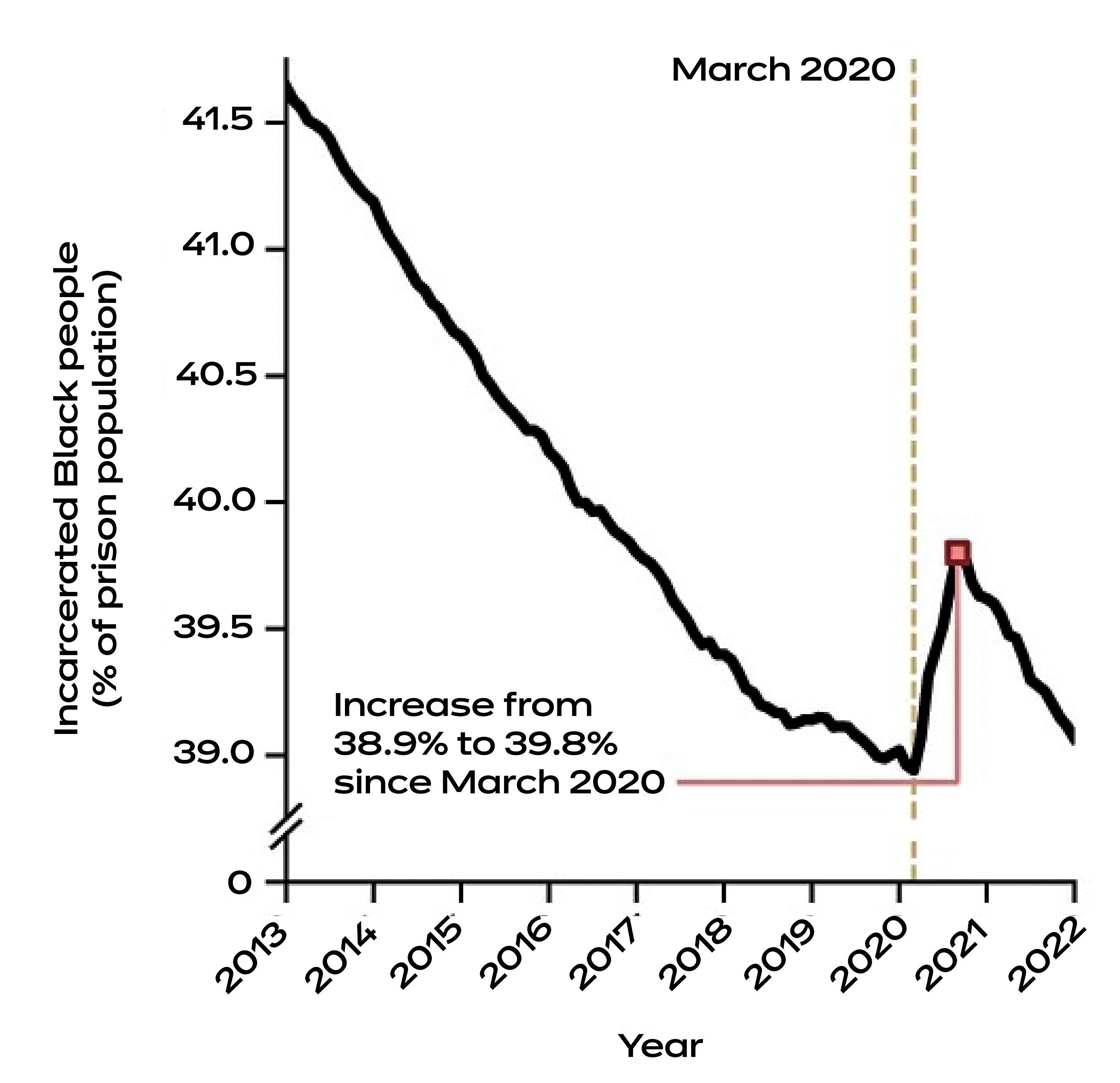

But as the overall prison population fell, the proportion of Black incarcerated people increased, according to data compiled by researchers at Harvard’s new Institute on Policing, Incarceration & Public Safety (IPIPS) at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research. Researchers attribute this finding to racial disparities in sentence length: Those with shorter sentences were released early, those with longer sentences remained locked up.

“This provides a very strong quantitative case that sentencing is the key mechanism of racial disparities in the system,” said Elizabeth Hinton, co-director of the Institute and lead author of the study along with Data for Justice Fellow Brennan Klein. On average, Black people are given sentences that are 20 percent longer than white people for committing the same crimes, according to a 2017 study by the U.S. Sentencing Commission.

Hinton and Klein’s paper, “COVID-19 amplified racial disparities in the US criminal legal system,” was published recently in the journal Nature.

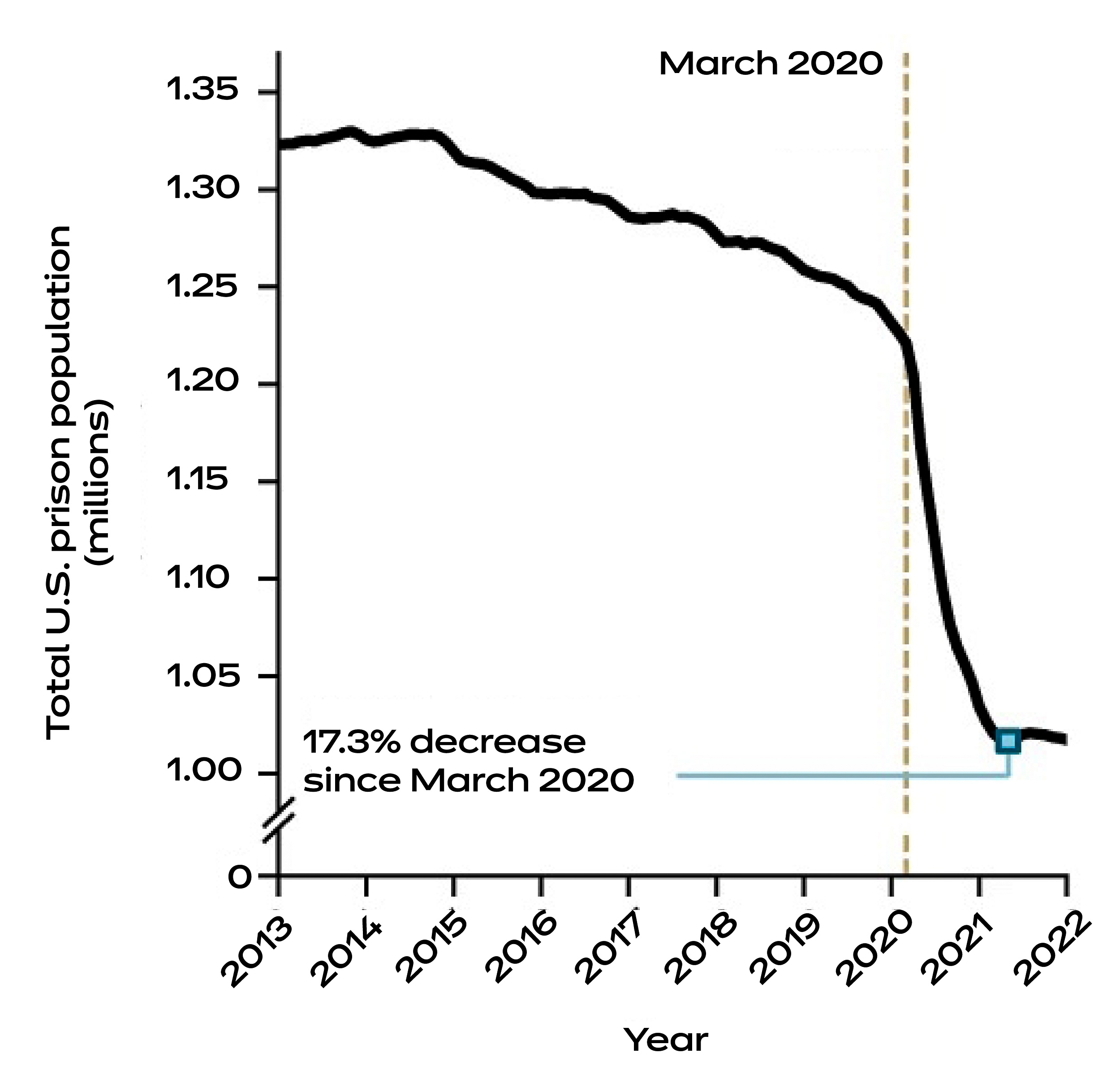

Between 2020 and 2021, the overall prison population decreased by 17.3 percent yet the proportion of incarcerated Black people rose by 0.9 percent.

Source: “COVID-19 amplified racial disparities in the US criminal legal system,” by Brennan Klein, C. Brandon Ogbunugafor, Benjamin J. Schafer, Zarana Bhadricha, Preeti Kori, Jim Sheldon, Nitish Kaza, Arush Sharma, Emily A. Wang, Tina Eliassi-Rad, Samuel V. Scarpino, and Elizabeth Hinton; via Nature

The project began when the researchers started looking at COVID cases and hospitalization rates within the U.S. prison population and realized an essential piece of information — the total number of incarcerated people in each state, broken down by race and sex — did not exist. They compiled a new original dataset showing racial demographics of U.S. prisons from 2013 to 2022, with help from other experts including C. Brandon Ogbunu, assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Yale, and Sam Scarpino, professor at the Institute for Experiential AI at Northeastern University.

“It turned out to not be a trivial thing to access,” Klein said. “The more we tried to actually get system-level data about the total number of people incarcerated, separated out by race and, in some cases, sex, we couldn’t find it.”

The researchers collected and analyzed data from every state, as well as the District of Columbia and the federal prison system, to get a better understanding of the demographics of the U.S. prison population over time.

Information gathering varied dramatically by state. Some corrections department websites provided easily accessible data, but Klein said the researchers had to scrape old data from some state websites that didn’t maintain a historic backlog. In other cases, they had to submit Freedom of Information Act requests if states didn’t have the information available to the public.

The trend consistently showed that while the overall prison population decreased by 17.3 percent between 2020 and 2021, the proportion of Black people in the prison population increased by 0.9 percent between March and November 2020. Klein said another way of thinking about the statistic is that on any given day if an incarcerated person is being released under normal procedures, they are more likely to be white.

“The phenomenon we observe is driven by two key ingredients: differences in average sentence lengths by race and a sudden drop in admissions,” Klein said. “If there is a prison system with these two factors, you’ll always find that this spike will occur.”

The authors referred to the COVID period as a “stress test,” which offers useful information on the criminal system and for studying decarceration and prison reform.

The authors also ruled out, through case study, any theory that the disparities were due to an increase in the severity of crimes committed by Black or Latino people during the pandemic.

“That was a possibility that we explored and found out that intake did not shape the result at all. It wasn’t about who was coming into prison; it was about who remained in prison, who was not getting released,” said Hinton, an associate professor of history and African American studies at Yale University and Yale Law professor.

The Institute on Policing, Incarceration & Public Safety launched in 2022 with a goal of advancing the understanding of systems and practices that inform the criminal legal system and public safety. In its inaugural year, it has also hosted panel discussions on a book about prison abolition and on the language of drill music.

“We’re really trying to start new conversations and get better scholarship out there to understand how we might reconceive ideas about public safety and think about how we can address some of these disparities that we see in both policing and incarceration,” said Hinton, a former Harvard professor. “As a thoroughly interdisciplinary institute taking a collaborative approach to the problem, we’re trying to provide not only scholars, but policymakers, practitioners, nonprofit organizations, and activists new tools to be able to address and confront the problem of mass criminalization, which is one of the biggest domestic problems facing American society today.”