War-scarred land

Detail of “Dried Pond along the Rio Grande,” Kirsten Luce (October 7, 2014, printed 2021).

© Kirsten Luce; image courtesy of the artist

Harvard curator reflects on photos she selected for award-winning book depicting collateral damage of U.S. military at home

In her recent book and accompanying exhibition, “Devour the Land” — honored at the 2022 PhotoBook Awards — curator Makeda Best considers how photographers have responded to the U.S. military’s impact on the environment since the 1970s.

Below, the Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography at the Harvard Art Museums walks us through a few of the images she selected.

“Mountain Range Surrounding the Nevada Test Site” (November 2017). From the series “Most People Were Silent” by Sim Chi Yin, Singaporean (b. Singapore 1978).

© Sim Chi Yin; image courtesy of the artist

Art and politics: photography as watchdog

In 2017, the Nobel Peace Center commissioned Sim Chi Yin to create a series of photographs related to the work of that year’s Nobel Peace Prize winner, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. Sim focused in part on the Nevada Test Site, northwest of Las Vegas, where 928 nuclear tests occurred above and below ground between 1951 and 1992. Taken at night, “Mountain Range Surrounding the Nevada Test Site” reveals a territory not widely accessible to or often seen by the public. An underlying theme in the exhibition is the lack of the public accessibility, and the “oversight” offered by photography. But the work is also stunningly beautiful, and Sim has spoken of her goal to use beauty as tool to draw in the viewer. This issue of beauty was so important to me as a curator in a different way. I am interested in how audiences could see and appreciate and admire the artistry of these works. People ask me all the time if this kind of photography and these subjects depress me, but they don’t — I look at all of the different approaches and I am inspired by how these artists can create such moving works. If you’ve ever been to any of these places, to the eye of someone who isn’t an artist — it doesn’t exactly look like much.

*

“CAD97012298, Fairchild Semiconductor Corp., San Jose, CA” (2016). From the series “In Plain Site” by Federica Armstrong, Italian (b. Novara 1971).

© Federica Armstrong; image courtesy of the artist

Another side of Silicon Valley

These photos by Federica Armstrong were a surprising discovery. Known for its tech companies today, Silicon Valley has another history that Armstrong surfaces in her images. The U.S. Air Force was one of the first proponents of microelectronics research and development — the technology would support the creation of weapons such as the supersonic B-70 bomber and the Minuteman nuclear missile. Dangerous chemical solvents involved in the making of microelectronics were often disposed of haphazardly: while some companies stored waste underground in containers that later leaked toxins into the groundwater, others did not even attempt such precautions. Armstrong documented these sites, many of which are being used for recreational and commercial purposes despite the fact that cleanup is still underway. She contrasts the ordinary qualities of her subject matter with unsettling information: the titles of the works include the EPA classification numbers that identify these places as Superfund sites, locations in the U.S. that require cleanup due to hazardous contamination. Armstrong is one of a few artists in the exhibition to integrate EPA nomenclature or documentation into their work.

*

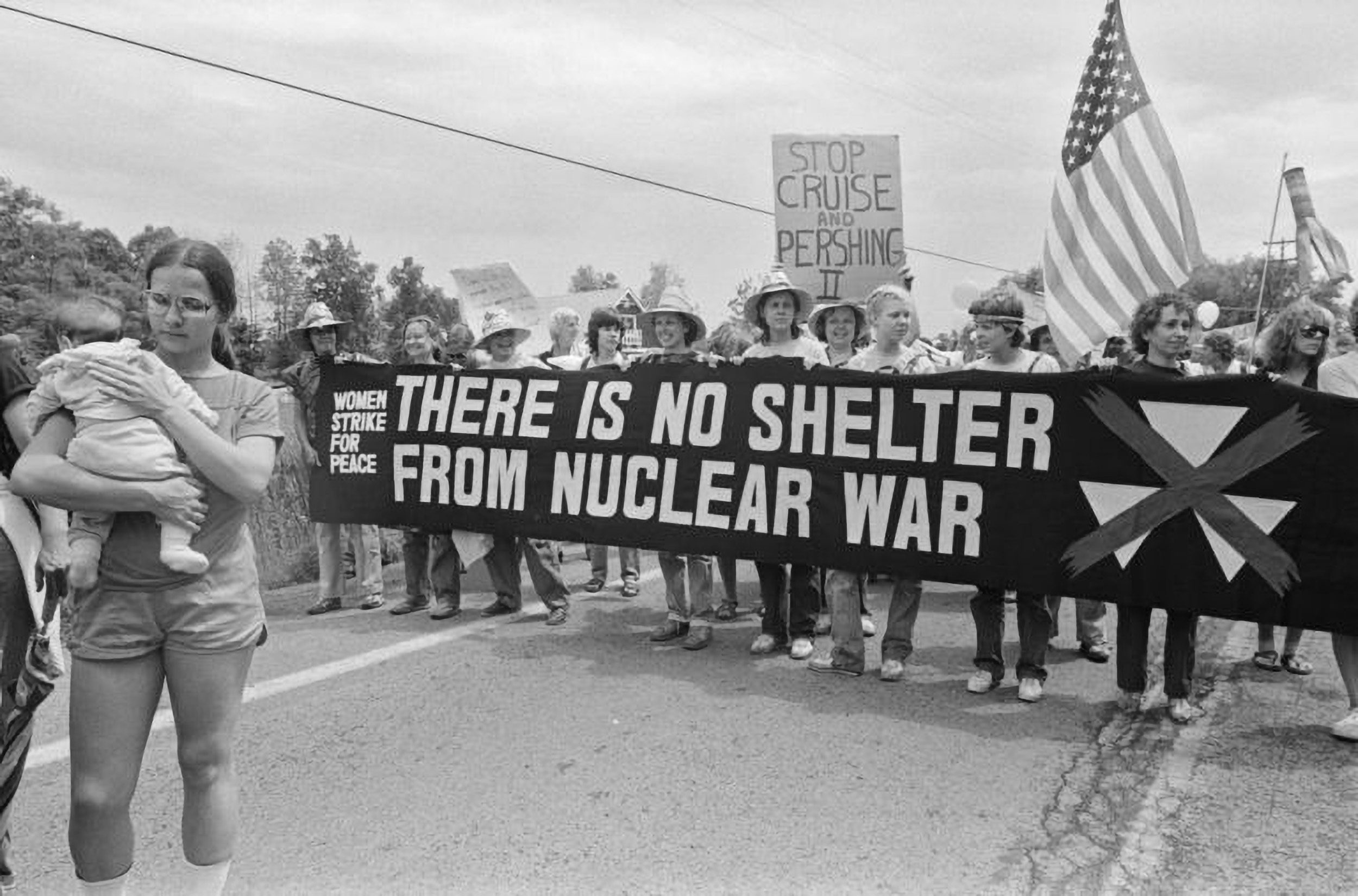

“Performance Art Against Nuclear Annihilation” (August 1983). From the series “Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice protest at the Seneca Army Depot” (Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University) by Mima Cataldo, American (b. New York, N.Y. 1943).

Photo by Mima Cataldo

‘Faced with horror, these women turn to creativity, to dance, to beauty as a form of protest’

I wanted “Devour the Land” to showcase the collection of a university art museum, and university collections. Last I checked, there are 51 repositories of photography at Harvard. We have incredible works that provide insight into photography’s development as a tool of social inquiry and means of personal expression. From the time of the medium’s invention, photography was part of the teaching here, and that commitment is reflected in our collections. At places like the Carpenter Center, Harvard helped to break down barriers between “fine art” and other forms of photography in exhibitions. “Devour the Land” continues this work.

This photograph is from Schlesinger Library. It depicts the Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice, originated at a conference on Global Feminism and Disarmament in June 1982 in New York City. Out of that, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom coordinated a meeting with the Upstate Feminist Peace Alliance to discuss the possibility of initiating a peace camp at the Seneca Army Depot, a storage facility for nuclear weapons, as a demonstration of U.S. opposition to the deployment of nuclear missiles. More women’s groups, some from Boston, too, joined the initiative, and Women’s Encampment for a Future of Peace and Justice was formed. Their encampment opened in July 1983. I find this image so inspirational — faced with horror, these women turn to creativity, to dance, to beauty as a form of protest and as bravery. This is a core idea of the project — what will we create in the face of this? Do we have the courage to confront and to create?

*

“A Housing Development Bordering the Starmet Superfund Site, Concord, Mass., USA” (July 3, 2016) by Nina Berman, American (b. New York, N.Y. 1960).

© Nina Berman; image courtesy of the artist

Just outside Walden Pond, a toxic dump

Nina Berman’s photograph was made in nearby Concord. Made at sites across the country, Berman’s series “Acknowledgment of Danger” takes its title from a waiver visitors must sign before entering the toxic grounds of a former military facility. In Concord, she photographed a new housing development in early morning light. Concord is known for its connections to the Revolutionary War and to the U.S. environmental movement. (The pictured site is six miles from Walden Pond, made famous by Henry David Thoreau’s 19th-century nature writing.) Here, Berman draws out this site’s link to modern warfare: Starmet Corp. (formerly Nuclear Metals Inc.) manufactured products from depleted uranium, primarily for armor-piercing ammunition, among other things. The company discharged toxic waste into an unlined holding basin for nearly 30 years, contaminating the soil and groundwater. In 2001, the facility was placed on the National Priorities List, an EPA registry of the nation’s most hazardous sites.

*

“A Resident Talks to Workers in the Hunter’s Point Neighborhood of San Francisco, Calif., on May 5, 2017.” From the series “Bombs in Our Backyard” by Ashley Gilbertson, Australian (b. Melbourne 1978).

© Ashley Gilbertson/VII; image courtesy of the artist

Story of environmental racism

It was important to me that the exhibition speak to the fact that communities of color are disproportionately impacted by this pollution and toxicity. Ashley Gilbertson made this photograph in a neighborhood in my hometown of San Francisco, called Hunter’s Point. The neighborhood was largely built on a former naval base, today a Superfund site. Growing up, I knew kids who lived here — heard them talk about their eczema and asthma. In 2017-18, Gilbertson, a contributor to the catalog, acclaimed for his photographs of conflict in the Middle East, turned his attention to the U.S., documenting pollution caused by the military for the investigative journalism nonprofit ProPublica. Gilbertson collaborated with journalist Abrahm Lustgarten (another contributor to the catalog) to produce a series of in-depth reports on the pollution from former chemical weapons test sites and the harmful ways the military has chosen to dispose of chemicals and munitions. In his larger series, Gilbertson shows how people and toxins intersect — from illness to activism to labor and daily life in a poisonous environment.

*

“Ellenton: the Last Traces of the Town Destroyed to Build the Savannah River Plant, Savannah River Plant: 300 Square Miles, Aiken, S.C.”

© Barbara Norfleet; image courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

Across America, documenting ‘former military facilities and the pollution left behind’

The story of the exhibition and the catalog is not just the environment, but it’s also about research methodologies and how art can inform and lead research. The curators of the Harvard Art Museums are uniquely committed to creating exhibitions that come out of research in our collections. As a Ph.D. from Harvard’s Department of the History of Art and Architecture, I am intimately familiar with this kind of research practice. Collections-based research led to my dissertation, and to my first book. “Devour the Land” bridges the Museums’ existing collections, as well as my interests in Civil War photography and contemporary documentary. Barbara Norfleet, who is interviewed in the catalog, is not only a dynamic photographer, but she also made a tremendous impact on our collections through her work leading the Carpenter Center decades ago. Today, those collections are the Harvard Art Museums’. Her personal interests were in land use and environmental justice. Because of her, we have works by photographers working on behalf of a group called the Atomic Photographers Guild — a group to which she belongs. The presence of these works in the collection were key to my thinking about “Devour the Land” — key to my argument that there was a parallel interest in photography and militarism. In this historic series, Norfleet traveled the country documenting former military facilities and the pollution left behind.

*

“Dried Pond Along the Rio Grande” (Oct. 7, 2014, printed 2021). From the series “As Above, So Below” by Kirsten Luce, American (b. Hyannis, Mass. 1981).

© Kirsten Luce; image courtesy of the artist

Twin tragedies at U.S. border

One section of the exhibition was titled “Other Battlefields” and it looked at other “wars” that impact our environment. This photograph depicts the U.S. southern border. Footprints in the mud indicate the human traffic through this marshy area, while the aerial perspective references the surveillance gaze of the Border Patrol. But the humanitarian crisis happening at the border is accompanied by an expanding environmental tragedy. The increased danger of crossing into the U.S. has forced people deeper into the surrounding wilderness in an effort to avoid detection and conceal their movements. There, they trample plant life and disrupt animal habitats. Meanwhile, the militarization of the border has introduced heavy equipment into fragile landscapes, where noise and air traffic disturb local fauna. Activists, conservationists, and wildlife managers have argued against plans to expand the border wall, which if continued will affect animal movement, destroy native plants and wildlife sanctuaries, and traverse sacred burial sites.