How ‘cult of grit’ masks myths about U.S. society

Emi Nietfeld argues in her new memoir it places all blame for not succeeding on individual, ignores bias, inequities

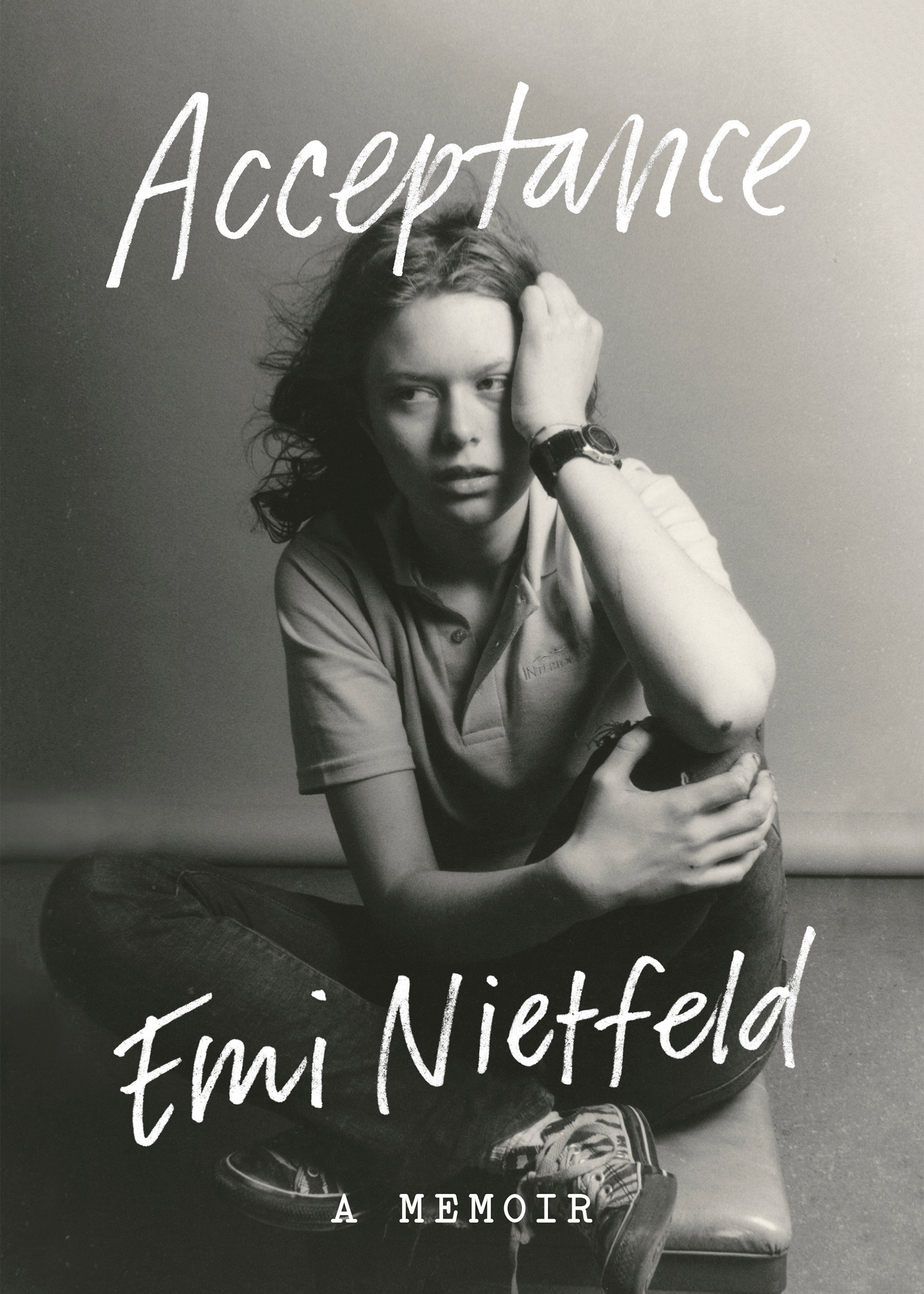

Penguin Press

In her powerful memoir “Acceptance,” Emi Nietfeld ’15 recounts her journey from foster care and homelessness to Harvard and Silicon Valley. The Gazette spoke with Nietfeld about how she learned, from her own experience, about the perils of the “gospel of resilience,” the myth of U.S. meritocracy, and the limits of the bootstrap mentality. Interview was edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Emi Nietfeld

GAZETTE: Your memoir chronicles your long, difficult childhood and youth, and it also questions the idea that to overcome adversity one must be “the perfect overcomer.” What’s problematic about this “gospel of resilience,” as you call it?

NIETFELD: When I was in high school and applying to college, I felt this tremendous pressure to not only tell colleges what had happened in my life, but to prove to them that I was made stronger by being in foster care and sleeping in my car. I felt like I had no room to be affected by these traumas, and it made me feel a lot of shame about the ways in which I was impacted. As I got older, I questioned this gospel of resilience because it meant that I had to show this perfect face to the world and act as if I was not struggling with PTSD.

My biggest problem with the cult of grit is that it takes social problems like racism, child abuse, and violence, and places the responsibility to deal with them onto the backs of individuals. In recent years, it has become a panacea for essentially any issue. Instead of addressing the underlying societal problems, we’ve shifted our focus to encouraging people to have resilience. I argue that it often blames already vulnerable people for bad things that are happening to them and that gets in the way of change taking place. It also strips people of empathy. When you believe that no matter what happens in someone’s life, they should be able to get over it and bounce back, that makes it harder to feel compassion or anger, or advocate on behalf of people who really need advocacy.

GAZETTE: In your own case what other factors helped you along the way?

NIETFELD: I’ve had a lot of things go wrong in my adolescence, from my parents’ mental illnesses to being in the child welfare system and being heavily medicated, but I also had a lot of things go right. And when you look at some of the research on what leads people to be able to cope with stress and trauma, some of the most important things are having a strong attachment to an adult, having a relatively calm early childhood, and feeling like you have a sense of agency in your life. I was lucky because I had all those things. I also had religion; I grew up with a belief that there was a bigger plan for my life and that through my actions I could work hard and do great things. That gave me a sense of control that so many young people who are in these systems lack. I also grew up in a house where going to college was an expectation; both of my parents went to college, and when she was a child my mom had dreamed of going to Stanford. She talked a lot about how her life would have been different if she had been able to go to that elite university. When I was in a dark place and looking for a way out, to me, the Ivy League was a natural target.

GAZETTE: So would you say the desire to reconcile the narrative of the perfect overcomer with your actual life experience played a big part in your decision to write this book?

NIETFELD: I started writing the initial ideas for the book back when I was 17, right after I applied to college. I felt that the experience of having to take my life story and twist it into this narrative that would be considered acceptable was so dehumanizing that it left me wondering who I was. After I graduated from Harvard and was working at Google, I couldn’t stop thinking about both the things that happened in high school and the experience of packaging them. I started writing this book as an attempt to understand those really complicated years, and through the process, I learned all these things I hadn’t known before, about family secrets, the ways that I was treated by medical professionals, and the systems that I was in. I went into writing the book thinking that I needed to write the story about me being this perfect overcomer who had gotten this incredible gift by getting into Harvard and that I was grateful and happy and not haunted. And it just didn’t work. I kept having to revisit the beliefs that I had around overcoming in order to get to the truth of my experience.

GAZETTE: Can you talk a bit more how about the resilience narrative actually hampers individual and societal progress?

NIETFELD: In recent years, as grit has become more and more part of the mainstream, we tend to focus on encouraging people to be resilient instead of addressing underlying problems that are affecting their lives. I wrote about how in Flint, Michigan, in 2015, after the water was found to be contaminated and the municipal government had covered it up, there were behavioral scientists in the schools, teaching young people to have a growth mindset before those kids even had safe drinking water. I think that resilience can be used as a “Get Out of Jail Free” card, where it really prevents us from both empathizing with people who desperately need empathy and making any meaningful changes in society.

GAZETTE: You write that you benefited from being white and pretty, that had you been Black or Latina you would have been placed in the justice system, not in the mental health system. That raises questions about privilege and undercuts claims of the U.S. as a pure meritocracy. How meritocratic is our society in your view?

NIETFELD: I grew up with the idea that America was the place where everyone had a chance; it was this sacred mythology. As I’ve grown up, that story has statistically become less and less true, as wealth and power consolidate and as people who were previously ignorant to racism have become more aware. When I hear the word meritocracy, I think of it as a shield to deflect criticism. Meritocracy can be a great ideal to have, but it’s easy to pretend something is a meritocracy when it’s not. For a long time, people saw my story and they would say, “You worked really hard, and you are proof that anyone can do it.” It’s important for me to point out all of these factors that influenced the way that I was able to get out of the situation and get into Harvard, like race, appearance, and my parents’ education, because otherwise stories like mine are weaponized and used to blame people who didn’t have those same benefits.

GAZETTE: Finally, what do you hope your readers can take away from your book?

NIETFELD: I hope that after reading “Acceptance,” people think critically about what resilience really is. Grit doesn’t come from telling people to be strong and swallow their feelings. Instead, it comes from having dreams that you’re working toward and having support from other people who have your back. I also hope that after reading this book, when readers encounter people who are struggling, instead of turning toward the idea of “What can that person do to be tougher?” they think about what they do in their communities to help people, whether it is as simple as mentoring or being a listening ear. Those small acts really make a difference and are what enable individuals to recover after tragedies.