Former White House aide Cassidy Hutchinson provided detailed testimony Tuesday as the House Select Committee continued its investigation of the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol.

AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin

Should Trump be charged in Capitol attack?

Government scholar says new disclosures make clear that refraining from action carries greatest risks to future of republic

What did the president know and when did he know it? Those were key questions during the Watergate hearings 50 years ago when investigators were looking into a cover-up of the infamous hotel break-in. These questions were again relevant when Cassidy Hutchinson, an assistant to Mark Meadows, former President Donald Trump’s chief of staff, testified Tuesday on the Jan. 6 Capitol attack. Hutchinson told members of the House Select Committee that Trump not only knew in advance that the crowd was armed and could turn violent but that he intended to participate in the attack.

Alexander Keyssar ’69, Ph.D. ’77, is the Matthew W. Stirling Jr. Professor of History and Social Policy at Harvard Kennedy School and author of “Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College?” (Harvard Univ. Press, 2020). Keyssar spoke to the Gazette about what the former president and his inner circle allegedly knew and did in the run-up to and on the day of the attack. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Alexander Keyssar

GAZETTE: Your reaction to what was revealed during Tuesday’s hearing — what stood out to you most?

KEYSSAR: There were several things that stood out to me. One was the revelation that there were a lot of people in the crowd who were armed, and the government knew that they were armed, and the White House knew that they were armed. That changes the complexion of the event. It doesn’t quite look like “peaceful protesters wandering around the Capitol but then it got out of hand.” I mean, that was always an implausible scenario anyway. But the people around the rally were armed and that was OK with the Trump administration. That was pretty striking.

I also found it striking and surprising that Trump wanted to go down to the Capitol. I think the image that most of us had [of him] until yesterday was, “Let me get these people stirred up and go down there and let them create havoc, but I’m going back home to be more comfortable and safe.” So, the notion that he wanted to go changes the complexion of the story. It’s very puzzling about what it was he thought he would do once he got there. I look forward to finding out, if we ever find out, which may be unlikely, what he thought he would do once he got there.

A lot of the rest struck me as filling in with some detail, and colorful details, things we knew or semi-knew or presumed were true. For example, that the White House was a cauldron of conflict and confusion and that the former president was in a rage. We have details about that now that make it vivid, but I don’t think that’s really new.

The last thing that I would say is that it focuses the spotlight on Mark Meadows. It’s not clear to what extent he was confused or playing a double game. He certainly seemed to be suggesting to people like White House counsel Pat Cipollone that he was doing his best to keep the president from escalating things. But then again, he called into the Willard Hotel meeting the night before and seems to be coordinating with the people who were trying to make it big. So, it focuses a spotlight on Meadows, but what we’re seeing is still a little blurry.

“There is a political risk in charging the former president because we don’t know how it will come out,” said Alexander Keyssar. “It will surely help to mobilize his base, and there would be harsh partisan rhetoric around it.”

Harvard file photo

GAZETTE: Violence is not new in American political history, but is there anything comparable to the allegations that a president was either interested in joining an armed mob that was about to sack Congress or in favor of having his own vice president attacked?

KEYSSAR: There was violence on the floor of the Senate in the 1850s, and there was violence out in Kansas of an extreme sort, and the history of Reconstruction, and the reversal of Reconstruction, is a story filled with violence in the South and elsewhere. But nothing is quite comparable to what we’ve been seeing.

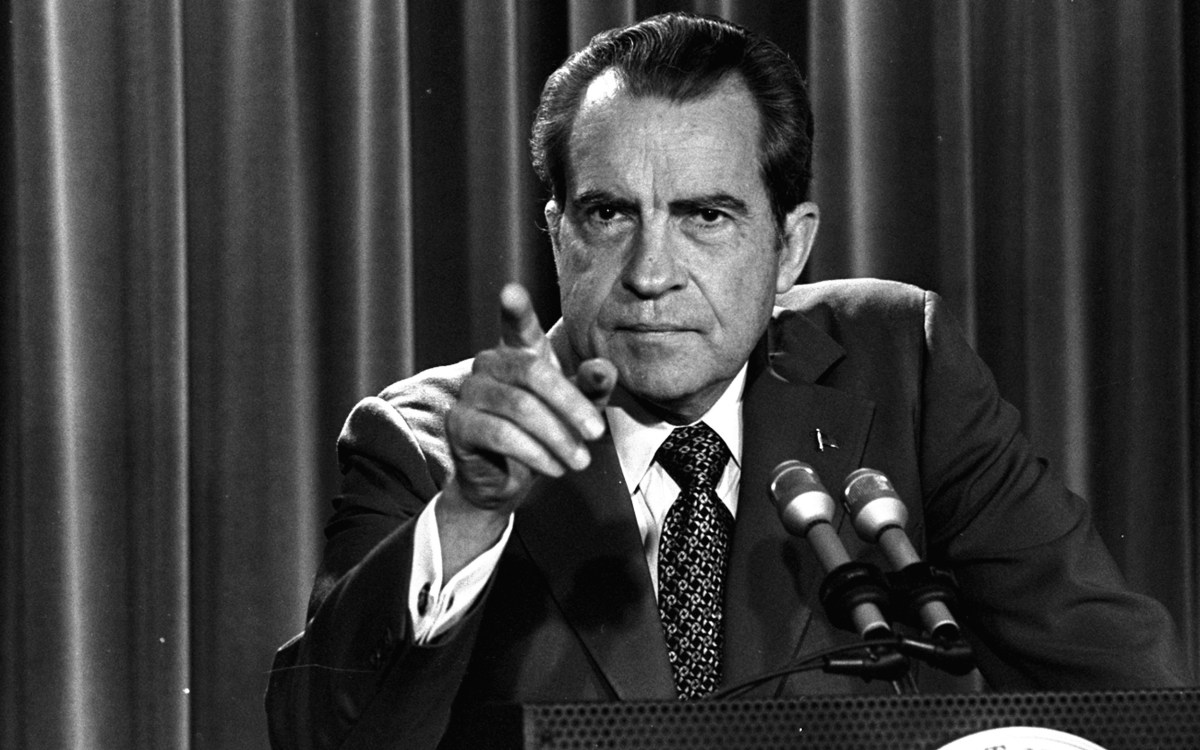

GAZETTE: Many are comparing Hutchinson’s allegations of malfeasance by a U.S. president and his top aides to John Dean’s revelations during the Watergate hearings 50 years ago. Is that a valid comparison given what we’ve learned?

KEYSSAR: I think we’re beyond John Dean territory. I don’t want to minimize Nixon’s offenses, and I don’t want to call them garden-variety. But basically, it was about the cover-up of an illegal break-in and the use of bribery to keep people silent, and then lying about it. This is a different story because when you put the whole story together here, all the pieces that we have, it does increasingly look like an attempted coup d’état. In some sense, it was a poorly organized and very incomplete attempt, but it was an attempt to alter the transfer of power from one presidential administration to another.

There was some image in Trump’s mind, and probably in the minds of the people who were over at the Willard Hotel, and God knows who in the White House. There was some image of violence or the threat of the use of violence or armed conflict, that would promote the cause of stopping the certification of electoral votes. That’s a pretty big deal.

GAZETTE: Many believe that politics will factor into Attorney General Merrick Garland’s decision about whether to charge the former president for his actions related to Jan. 6. His perceived dilemma is that he risks further polarizing the country and reinforces the perception that the DOJ is political by moving forward. But if he doesn’t, he also risks polarizing the country and reinforces a perception that the powerful are above the law. How do you see this debate?

KEYSSAR: There is a political risk in charging the former president because we don’t know how it will come out. It will surely help to mobilize his base, and there would be harsh partisan rhetoric around it. Democrats will be blamed for doing something that was extremely partisan.

On the other hand, and I think this is something that Tuesday’s hearing just brought home or put in Technicolor, is what would it mean to let somebody who engaged in those activities escape any sanction or even attempted sanction? Especially as somebody who is actively considering trying to become president again. So, in my mind, the risk of not taking legal action for the health of the republic is greater than the risk of taking action.

GAZETTE: If someone broke the law, should it matter whether the person was a president at one time? Should the Department of Justice be factoring politics into this?

KEYSSAR: I gather from my friends who are lawyers that that’s actually a tricky question. I’m comfortable saying it shouldn’t matter who committed the crime. But what I hear from lawyers is that prosecutors consider all the time what the likely outcomes might be if they bring a case, so it wouldn’t be stepping outside of normal practice as I understand it as a non-lawyer.

History is replete with examples of decisions made or actions taken based on gauging political impact, and gauging it wrongly, and making a mistake. It’s very hard to predict what impacts will look like in the future, not just two years from now, but 10 years from now. It’s very hard to predict or control those outcomes. Given that, to not take action would be to license any future inhabitants of the White House to engage in efforts to stay in office and sponsor acts of violence in order to stay in office.