Panelists Dan Schrag (from left), John Holdren, Terry Tempest Williams, and Jim Stock debated the challenges that could undermine today’s efforts to fight climate change.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Way forward on climate change

Panel looks at success, failures since 1st Earth Day in 1970, challenges such as Ukraine, U.S. political divisiveness ahead

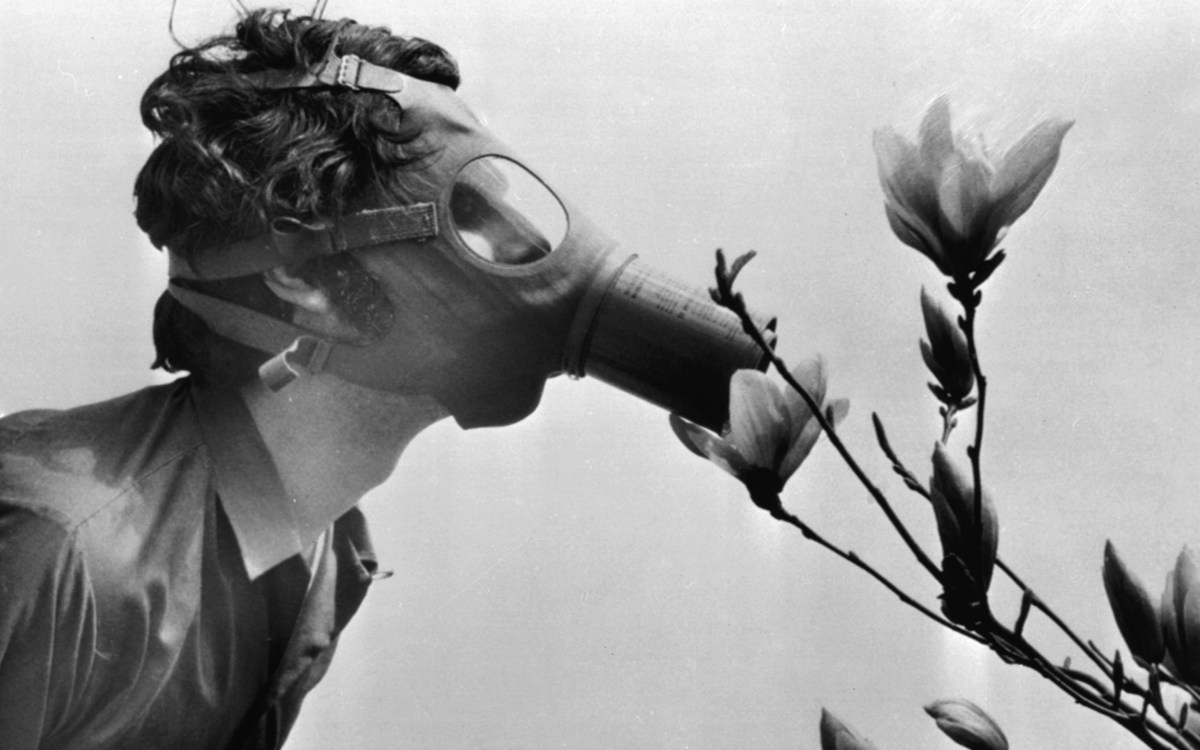

John Holdren took his wife and kids, both still toddlers in strollers, to the first Earth Day celebration in California in 1970. At the time, Holdren recalled, most people were worried about air and water pollution and urban smog.

“Today, of course, climate change looms very large in the constellation of environmental challenges,” said Holdren, the Teresa and John Heinz Research Professor of Environmental Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School, during a panel on Thursday, the eve of Earth Day.

Hosted by the Harvard University Center for the Environment and the Office of the Vice Provost for Climate and Sustainability, the group of experts discussed progress scientists and policy makers have made — and, more critically, failed to make — since that first Earth Day. They also debated the challenges that could undermine today’s efforts to fight climate change, including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a divisive political climate that includes some who either deny the existence of the problem or believe the severity is overblown.

“I don’t see grief as the opposite of hope,” said Terry Tempest Williams, writer-in-residence at the Harvard Divinity School and environmental author and advocate, referring to the sense of loss shared by some over the damage already done. “But if we acknowledge the world is dying then we can move past the depression and do something.”

In 2016 Williams and her husband tried to do something big in Utah: They paid to lease about 1,120 acres of public land reserved for oil and gas drilling, planning to keep it dormant. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management subsequently canceled the lease. Williams’ state is experiencing some of the worst consequences of climate change, including bigger and more frequent wildfires, like the 2020 East Fork Wildfire, which burned an area of close to 90,000 acres (about 3½ times the size of New York City). Floods and mudslides rage through the fires’ burn areas. Birds have fled. People aren’t concerned about policy, Williams said; they worry whether they’ll have enough water (levels of both Great Salt Lake and Colorado River are plummeting due to diversion), if their house will burn, or what the whirling dust will do to their lungs.

Even the Arctic tundra is burning, said Holdren, who was also a science adviser to President Barack Obama. Wildfires, extreme storms, droughts, vector-borne diseases — like malaria — are all spreading and getting worse. “We haven’t avoided the worst impact,” he said, thinking back to when he attended the signing of the Paris Agreement in 2015 during which 196 countries agreed to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Another 2015 attendee asked him whether he was happy with the agreement. “I would have been happy 20 years ago,” he responded.

“The eyes of the future are looking back at us, and they are praying for us to see beyond our own time. Wild mercy is in our hands.”

Terry Tempest Williams, “Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place”

Today, climate change is already affecting people where they live and work. Even for those it does not directly affect, they can watch its impacts on screens. In the 1990s, these visuals didn’t exist yet to motivate people to act — and that inaction hurts today’s most vulnerable communities, like Indigenous Alaskan tribes, Holdren said. “People who have done the least to create the problem are suffering the worst impacts.”

“Our generation has really screwed up,” said Jim Stock, vice provost for climate and sustainability, who also served in Obama’s White House. While some progress has been made, especially to reduce smog and grow the wind and solar energy industries, “We should have done far more in the 1990s,” he said. “We allowed a political system to hold the science hostage.”

Today, Stock said, individuals can still make changes, like insulating their attics or eating less meat, but sparking systemic changes, like teaching climate change in public schools and putting pressure on institutions and politicians to live up to their promises, can be more impactful. As vice provost, Stock’s responsibilities include working with faculty, students, staff, and academic leadership from across the University to guide and further develop Harvard’s strategies for advancing climate research and its global impact.

Broader changes on a national or international scale are still hard to make, especially when other pressing challenges, like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, demand immediate global attention. The recent energy crisis, a result of Europe’s dependence on Russian natural gas, points to a pattern, Stock said, where national security concerns often follow fossil fuels. The dependence makes us vulnerable, he continued, but while some see this as an opportunity to shift to more stable renewable energy sources, like wind and solar, others say it’s a reason to start more drilling.

“I think we’re in a terrible cycle. A lack of leadership, a lack of will,” Williams said.

But Dan Schrag, the director of the Harvard University Center for the Environment who moderated the discussion, sees room for hope — if not in his own generation, then in the next, which is far more engaged in climate change activism. “It’s never too late to keep fighting. If we can’t keep it to 1.5, let’s try for 2. If not 2, then 3,” he said, referring the Paris Agreement goal.

To conclude, Schrag asked Williams to read an excerpt from her essay “Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place.”

“The eyes of the future are looking back at us, and they are praying for us to see beyond our own time,” Williams read. “Wild mercy is in our hands.”