A Pace College student in a gas mask “smells” a magnolia blossom in New York City on Earth Day, 1970.

AP file photo

The culture of Earth Day

How the event moved environmentalism into legislatures, the boardroom, and the living room

When Earth Day began on April 22, 1970, many people wondered if the end might be near. Concern was fervent enough, in fact, that 20 million Americans — 10 percent of the population — packed demonstrations and teach-ins in cities and towns around the nation.

Nobel-winning Harvard biochemist George Wald articulated the fears in a speech later that year at the University of Rhode Island, warning that civilization would end within 15 to 30 years unless immediate action were taken against threats facing mankind, including pollution, overpopulation, and potential nuclear war.

As it turns 50, Earth Day is widely recognized as having ignited the modern environmental movement and brought those concerns into classrooms, legislatures, courtrooms, boardrooms, and living rooms, often borne along by popular culture.

It was largely triggered by the Santa Barbara oil spill of January 1969, an environmental disaster that dumped the equivalent of 100,000 barrels of crude into Santa Barbara Channel, killing thousands of sea birds and mammals. This coincided with other disturbances around that time: the burning of the fouled, fuel-slicked Cuyahoga River, the near-death of Lake Erie, and the near-extinction of the bald eagle. These events crystallized a concern about the environment that had been growing for decades.

According to Harvard Department of History research associate Alexander More, the roots of environmentalism go back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the Sierra Club was founded and conservationist President Theodore Roosevelt oversaw the establishment of a number of the early national parks, several bird and game preserves, and 150 national forests. “Roosevelt always emphasized the importance of spending time in the wilderness in order to forge your character.”

Nuclear tests in 1954‒55 caused worries about fallout, and Rachel Carson’s 1962 book “Silent Spring” raised concern about the dangers of pesticides, selling a million copies over its first two years and leading to a ban on DDT. But it wasn’t until decade’s end that the concerns coalesced into a movement, joining Civil Rights and the Vietnam War as the issues at the top of college students’ minds.

“No one even used the phrase ‘environmental movement’ until around 1970,” said Adam Rome, professor of environment and sustainability at the University at Buffalo. “There was activism around certain issues — air pollution, people trying to outmode DDT or to save certain lakes. But there was no sense yet that all this was part of some huge issue, which people started calling the environmental crisis. By 1970 it is evident that this is of more concern to Americans than it’s ever been before.”

Earth Day was created by Democratic Sen. Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, who initially conceived it as a “National Environmental Teach-In” — billing that organizers hoped would ensure its reception on college campuses. April 22 was chosen as a college-friendly day: a safe enough distance from both winter and finals, and a Wednesday, when students wouldn’t be away for the weekend.

“It was bipartisan to an extent that would not be fathomable today. A lot of conservatives as well as liberals agreed that it was a pressing issue.”

Adam Rome, Professor of Environment and Sustainability at the University of Buffalo

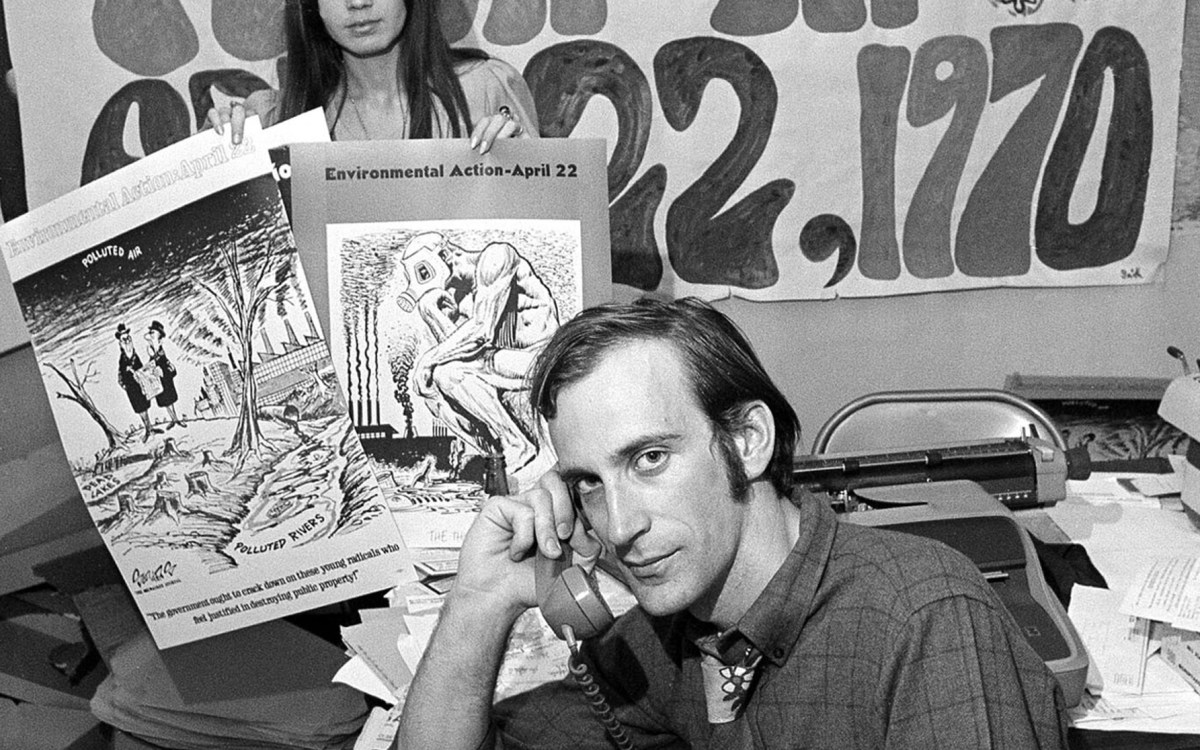

Nelson’s office was itself a hotbed of college-aged political activists. Chief among them was Denis Hayes, then a student at the Kennedy School of Government — at 25, the most senior member of Nelson’s paid staff (which would add two other Harvard students, Steven Cotton and Andrew Garling). Hayes was largely responsible for building momentum for the event, linking it with the social upheaval of the era. The name Earth Day ultimately was chosen when a “progressive advertising guy” came by the office offering help, Hayes told Time magazine last year. “Youthful vitality and passion form the engine of these things,” he said.

The success of Earth Day went well beyond expectations. More than 2,000 colleges took part, along with thousands of primary and secondary schools and communities large and small. Fifth Avenue in New York was closed, and Congress shut down as two-thirds of its members spoke at events. “It was bipartisan to an extent that would not be fathomable today,” Rome said. “A lot of conservatives as well as liberals agreed that it was a pressing issue.”

Earth Day had an unlikely ally in President Richard Nixon, who planted a tree on the White House lawn to commemorate it. The sincerity of Nixon’s commitment has long been debated, but he did seem convinced for a time that environmentalism would be part of his legacy. On New Year’s Day 1970 he signed the National Environmental Policy Act, a symbolic launching of an environmentally focused decade, and he put it into action by creating the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in September. George H.W. Bush was on the original short list of EPA heads, but was passed over because of his oil connections. The job instead went to William Ruckelshaus, who successfully both banned DDT and implemented the 1970 Clean Air Act, before resigning in a dispute with Nixon over Watergate.

“I don’t believe that Nixon was personally committed,” said Rome. “But he was reacting. He knew, among other things, that his next opponent would be a Democrat who cared a lot about environmental issues. And the first heads he appointed to the EPA were pretty radical. The idea was that the EPA wouldn’t worry about economics or politics, that it would be the voice of the environment.”

According to More, the aide who persuaded Nixon to embrace environmentalism was another future Watergate figure, White House counsel John Ehrlichman. “He was the guy who started it all, a really cunning political mind. He saw the same thing that Gaylord Nelson saw, that young and even middle-aged people were mobilizing. So why not harness this very strong social activism? He saw an opportunity not to be missed, to increase the popularity of Richard Nixon.”

“People are seeing what is happening now and saying ‘OK, we are surviving. So can we reset our economy in ways that we can learn from this crisis, find the silver lining and pollute less?’”

Alexander More, Harvard Department of History research associate

To a large extent, the 1970s really did become an environmental decade. After the first Earth Day, the ecology became a fixture in hit songs (Joni Mitchell’s “Big Yellow Taxi” in 1970 and Marvin Gaye’s “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” a year later) and movies (1973’s dystopian “Soylent Green” and, most famously, 1979’s antinuke “The China Syndrome”). Then there were best-selling books, including “The Environmental Handbook: Prepared for the First Environmental Teach-In,” edited by Garrett De Bell, 1970; “Diet for a Small Planet” by Frances Moore Lappé, 1971; and for children, “The Lorax” by Dr. Seuss, also in 1971.

In time for Earth Day 1971, the Keep America Beautiful nonprofit commissioned a widely viewed and remembered TV commercial showing a polluted landscape surveyed by a tearful Native American elder (played, in a bit of whitewashed casting, by “Iron Eyes” Cody, a Sicilian-American actor). In 1976 the country got one of its most environmentally active presidents, Jimmy Carter, who oversaw passage of the Soil and Water Conservation Act, along with fuel-efficiency standards for cars — though these would be significantly relaxed under President Ronald Reagan, as would the regulatory power of the EPA.

Even though the string of cultural products has been unbroken, recent legal and regulatory prospects for the environment may seem bleaker as the Trump administration campaigns to roll back protections. But, Rome noted, it is worthwhile recalling all the progress that has been made over the years. For one thing, he said, you didn’t find environmental reporters at newspapers or environmental studies programs at universities in 1970; both developed in Earth Day’s wake. He added that the planet is less polluted now than it was 50 years ago — and if Earth Day hadn’t been canceled due to the pandemic, participants undoubtedly would have celebrated the legal victory in late March by the Sioux Tribe, which is seeking to halt the Dakota Access Pipeline

More hopes that this Earth Day can prompt a hard look at a wide range of current issues, including the future of wet markets, which sell fresh produce and often live animals. The coronavirus is thought to have originated in one. “Maybe this tragedy can give us a license to think about the 50 years of progress we have made. People are seeing what is happening now and saying ‘OK, we are surviving. So can we reset our economy in ways that we can learn from this crisis, find the silver lining and pollute less?’”