Julia Child brandishes a saber while preparing Napoleon chicken for a 1970 episode of “The French Chef.”

Photo by Paul Child; courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute

Becoming Julia Child

Culinary expert at Schlesinger Library, which holds celebrity chef’s archival collection, examines her enduring legacy

Nearly 60 years after the woman who was neither French nor a chef first appeared on Boston public television as “The French Chef,” Julia Child is still inspiring home cooks and fascinating TV showrunners and filmmakers.

Most recent is the HBO Max drama series, “Julia,” about her life and beginnings in public TV, a cooking competition, “The Julia Child Challenge” on Discovery Plus, and the 2021 documentary, “Julia,” that debuted last fall.

The Gazette spoke with culinary expert Marylène Altieri, curator of books and printed materials at Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library, which holds the collection of Child’s papers, photographs, audio and video recordings, and private cookbook library. Library staff also consulted with the creators of the “Julia” series and David Hyde Pierce, the actor who plays Paul Child, when the project was in development. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Marylène Altieri

GAZETTE: Why do you think Julia Child remains such an enduring figure of fascination?

ALTIERI: A couple of things are at play. One is just the improbability of her success. Today’s standards of television expectations of how women should look while they’re cooking — the low-cut tight tops, the beautifully arranged hair and makeup — is still a reflection of what was expected of women on television then. There had been women cooking on television already, but they were expected to be very solemn and restrained in their approach. She didn’t look like a glamorous woman, and she didn’t behave like a restrained woman. There’s this incredible personality at work there that somehow, against all odds, succeeds with the public.

And then behind that, there was also the success of her books, particularly “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.” The people in charge had no idea how successful that book was going to be either. They thought it was too long, too complicated. And yet, it became phenomenally successful, too. So, this against-all-odds narrative continues to appeal to people because what we’re fed most of the time on television is perfect-looking television hosts and the cookbooks have to be perfect coffee table books. And her work didn’t fit into either of those categories very neatly. And then, the fact that she was around for such a long time too. She didn’t just do one show and go away. She was in the public eye for years.

“She didn’t look like a glamorous woman, and she didn’t behave like a restrained woman. There’s this incredible personality at work there that somehow, against all odds, succeeds with the public.”

GAZETTE: She’s credited with introducing French cooking to Americans, with revolutionizing cookbook publishing, and popularizing TV cooking shows. In what other ways was she influential?

ALTIERI: Julia comes up at a time when a lot of women aspired to be wonderful cooks, but everyday cooking was drudgery to them. I’ve talked to women who lived in Cambridge at the time that “Mastering” came out. A group of faculty wives and faculty women, some were teaching at Harvard, met at the Wursthaus every week for lunch and went through the book and decided what recipes they were going to cook for their dinners that week.

These were people who had very busy lives and plenty else to do, but they aspired to reach that level of cooking. They wanted to do it and do it well. So, she did inspire a lot of people to want to cook better and went to great efforts to write her recipes in a way that Americans could understand. Julia insisted that it had to be step-by-step and that it had to work with American ingredients.

And then, there were women who wanted to work in restaurants. She never had, herself, but they came to her — Lydia Shire, Jody Adams, Michela Larson — all the different chefs and restaurateurs who have spoken about how inspirational she was. Nina Simonds, for example, who writes books on Chinese cookery, went to Julia Child to ask her how do you go to another country and learn? Julia gave her a lot of advice and recommendations. Nina went on to translate Chinese cookbooks into English and wrote many highly regarded works herself. Julia, famously, was so accessible that she would answer her telephone on Thanksgiving Day and talk to people who were having trouble with their turkey. She just influenced people in so many different ways and was a model for women in general beyond cooking.

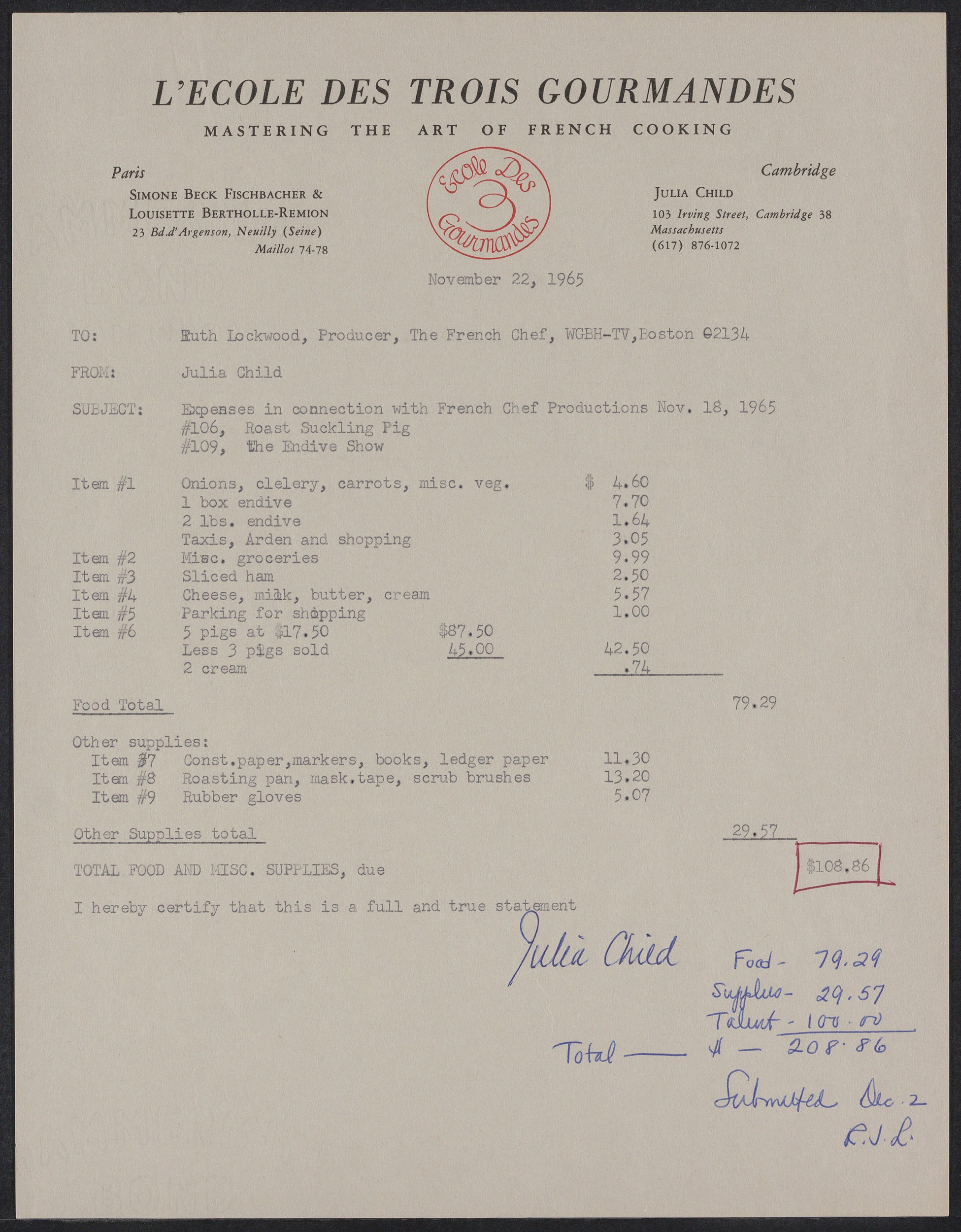

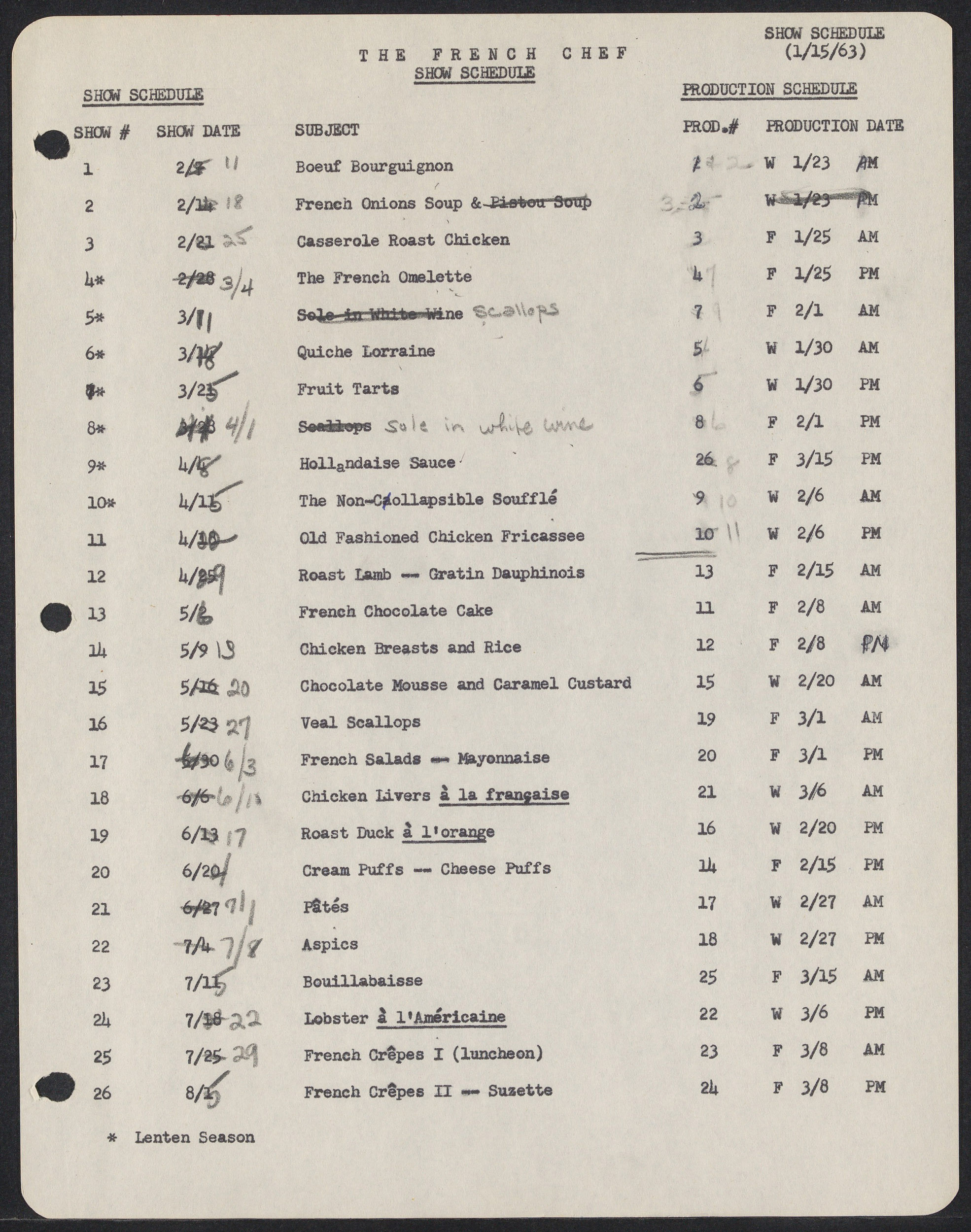

Receipt for reimbursement by WGBH for expenses incurred for episodes on roast suckling pig and “The Endive Show“; production schedule for Child’s first shows in 1963.

Julia Child Materials © 2022 The Julia Child Foundation for Gastronomy and the Culinary Arts; courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute

GAZETTE: What are some of the more unusual items in the collection?

ALTIERI: When the show started at WGBH, there was no studio kitchen. There was no cooking equipment. They had to bring everything in themselves. They would load up their car with pots and pans and all the food that was going to be used. She would have gone shopping and kept all the receipts and stapled all those receipts to a copy of the episode outline because she had to submit those for reimbursement. Her files are a real case study in television history.

It’s really remarkable to see how the show was put together: She and Paul [Child, her husband,] would write up a daily, minute-by-minute plan for the day of shooting. I think they would shoot two episodes on a single day, so there’d be the morning session and the afternoon session. And it’s all in these handwritten lists of things. “9:15: Julia puts on makeup, 9:30: Get in car; go to studio.” It’s all spelled out.

There’s also an instruction sheet for Paul because he would be standing off to the side, off-camera. When the camera wasn’t in his area, he would be slipping things on and off the counter that she was going to need. She’s going to need this cutting board, so he’d put that on and remove the peeler or whatever. There are sketches he made of how the top of the work surface was supposed to be laid out for every episode. The two of them were just phenomenally organized and pretty much had to be to pull this off. It was a real high-wire act.

“Julia, famously, was so accessible that she would answer her telephone on Thanksgiving Day and talk to people who were having trouble with their turkey.“

GAZETTE: Julia graduated from Smith College. How did her cookbooks, letters, papers, and personal photographs end up at Radcliffe and Schlesinger Library?

ALTIERI: Avis De Voto is a key figure. Avis had been a book editor at Houghton Mifflin. Julia Child and her partners first submitted their book idea to Houghton Mifflin and signed a contract to publish that book. But when the manuscript started arriving and was so huge — one chapter was hundreds of pages — Houghton Mifflin pulled out. It was terribly disappointing. Julia had already been working on the book for years.

Bernard De Voto, Avis’ husband, was writing for Harper’s magazine about the declining quality of paring knives. Julia and Paul read that in France. Julia wrote him a letter and offered to send him a French knife. Avis was the one who replied. She found out Julia was writing this book, and said, “Well, I’m a book agent.” They began corresponding and Avis took on the task of landing it with a publisher. But then they started corresponding about all sorts of things.

Eventually, Bernard De Voto died very suddenly, and Avis needed to get a job. The job she got was assistant to the dean at Radcliffe College. Avis persuaded Julia and Paul to move to Cambridge when Paul retired from overseas service. Avis was working in Fay House and got to know Schlesinger Library, which collected the correspondence of women. After she and Julia had been corresponding for over a decade, she said to Julia, “We’ve got these great letters. We should offer them to Schlesinger Library. And, by the way, the library has a cookbook collection too.”

We already had the collection of Samuel and Narcisse Chamberlain, famous gastronomic writers; the etiquette books of Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger were here; suffrage cookbooks, fund-raising cookbooks, and other domestic manuals that had to do with cookery. When Julia saw this, she decided not only to give the letters, but to give her papers and her personal library. She committed in the late ’60s to giving all her material eventually to Schlesinger Library.

Julia then went to town on helping the library raise funds to acquire more culinary material because that was not a budget line back then. Julia did all these cooking demonstrations here at the library and she persuaded other people to come. Jacques Pepin, Craig Claiborne, and Pierre Franey, all sorts of people did cooking demonstrations here to raise money for the collection. Everyone here had known her. That I use her first name all the time is an indication of how familiar we all feel with her, not a sign of disrespect. She was, and remains, Our Julia.