Looking at how ‘Hair’ works

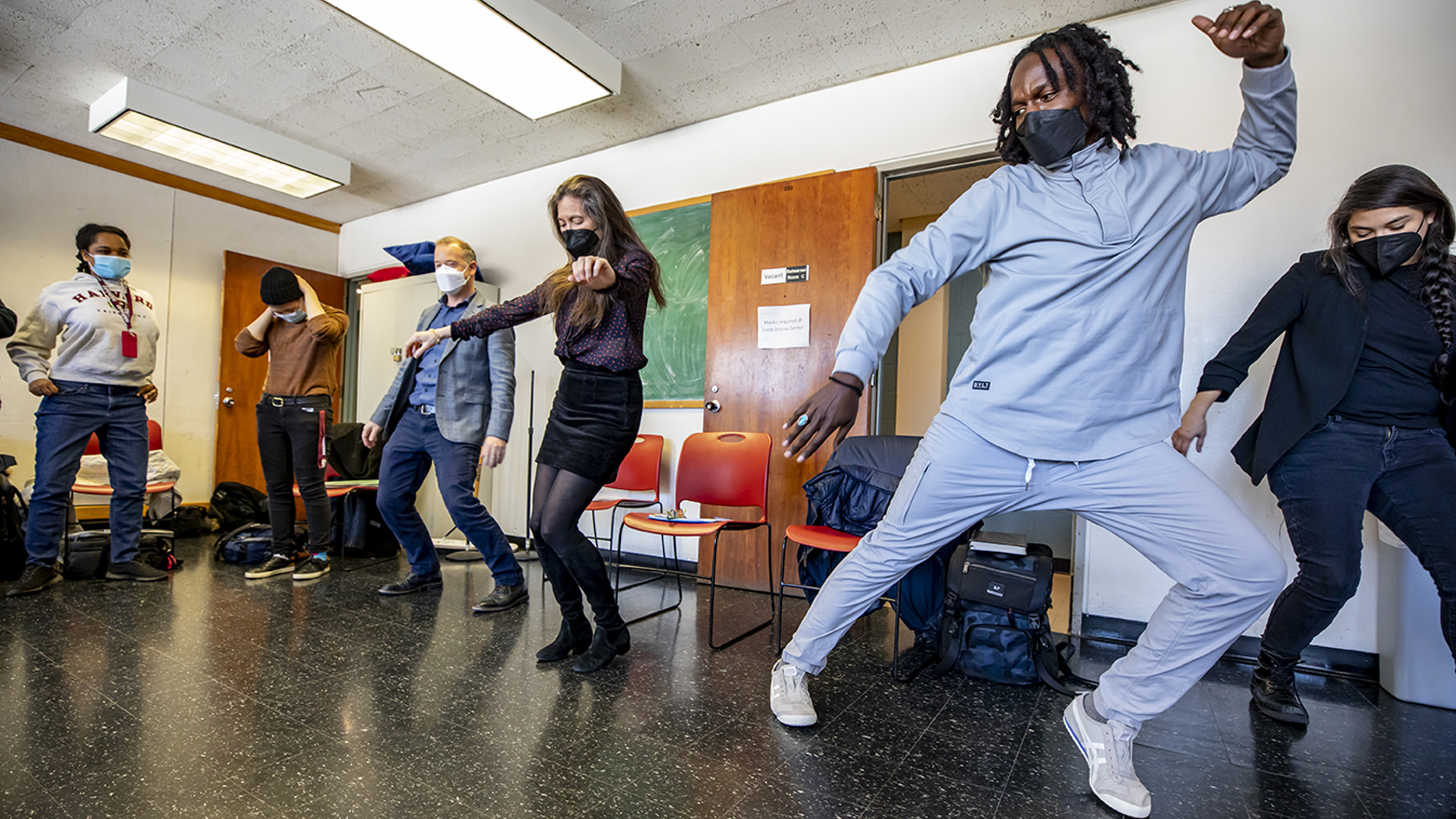

Students improvise a scene in the Theater, Dance & Media class “The Power and Relevance of the American Musical.”

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Theater, Dance & Media course — part theory and part hands-on — examines medium, message of musical theater

The musical “Hair” debuted on Broadway in 1968 and shocked the theater establishment. It wasn’t so much the story — a young man who is part of a “tribe” of hippies must decide whether to resist the Vietnam draft. But “Hair” gloried in its explicitly sexual and political song lyrics, rock music score, onstage nudity, and audience interaction, all of it a rejection of the traditional musical and a reflection of the show’s defiant ethos as well as the popular and social consciousness of the time.

The new modes of storytelling and staging that “Hair” brought to American theater were topics in the spring Theater, Dance & Media course “The Power and Relevance of the American Musical: ‘1776’ and Other Musicals.” The course is taught by Diane Paulus, Terrie and Bradley Bloom Artistic Director of the American Repertory Theater; Ryan McKittrick, A.R.T. director of artistic programs and dramaturg; and Jeffrey L. Page, lecturer in TDM.

Students studied the uses of music, lyrics, choreography, and stage design as tools to convey messages and intentions of creators. Topics include song as a dramatic tool in “Dreamgirls,” the power of adaptation and representation in “The Wiz,” and humor as a vehicle for information in “Hamilton.” Students create short pieces in class and instructors provide the intellectual framework for their analysis and stage work lessons for their time behind the curtain.

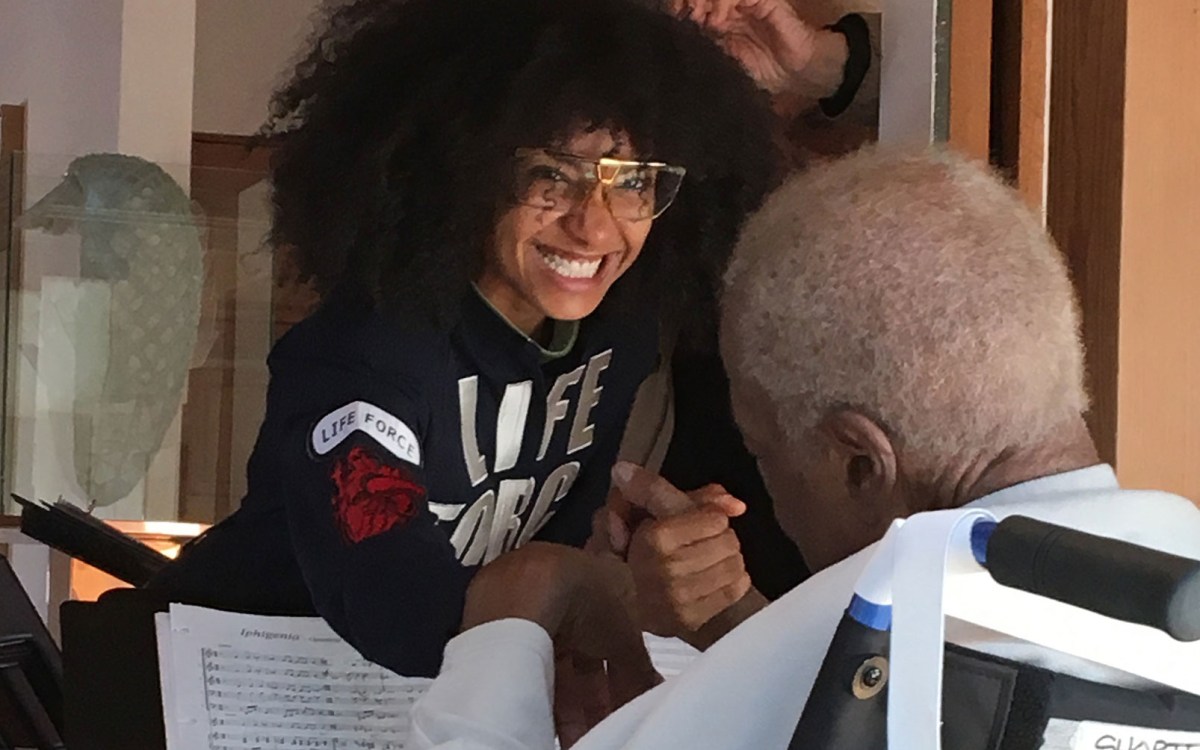

Course instructors Ryan McKittrick (from left), Diane Paulus, and Jeffrey L. Page lead an exercise.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

“This is an analytical class on the American musical that is being offered by three instructors who work in a professional theater,” said Paulus. “To show that what we do inside the theater has a rigor and has inquiry — and to share that aspect of the arts with students is very important.”

During a recent unit on art as protest, students listened to Paulus take apart how elements of form came together to make “Hair” a cultural landmark on its debut. Paulus also shared experiences of directing the most recent “Hair” revival, which received a 2009 Tony award for Best Revival (and was lauded in The New York Times for “defying expectations” by rediscovering at its heart the energy and poignance of “the waning days of … adolescence”).

She told of the choice to hold open-call auditions for the first iteration of the revival — a concert in Central Park — to bring in a range of talent, and recalled seeing a Vietnam war veteran in the audience be overcome with emotion.

“A show can have different meanings across generations and socio-political contexts,” she told the students. “‘Hair’ was theater of the moment in 1968. Forty years later, we asked: What’s the intention behind that? And what does a revival mean in its time?”

The question wasn’t abstract for Paulus. She and Page are co-directors (and Page is the choreographer) of a new revival of “1776,” the 1969 musical about the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The show will premiere at the A.R.T. in May after a two-year delay due to the pandemic.

Students Jade Woods (from left), David Moberg, Anna Blanchfield, and Amelie Julicher collaborate.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

“1776” acts as a kind of throughline for the semester. Students began the course by analyzing the form and original performance context of the show. Paulus and Page shared their research process, which included theoretical work on theater and the study of U.S. history.

“1776” was an unconventional show at the time; it was a historical costume drama with fewer songs than its contemporaries and lacked a traditional female chorus. It was also the first Broadway show to be performed at the White House. The A.R.T. revival features a diverse cast representing many genders, races, and ethnicities.

As live theater and its artists recover from financial, mental, and physical blows taken during the COVID-19 outbreak, McKittrick was also excited for the course’s first fully in-person semester since lockdown and the chance for students to experience theater work in person.

“We talk a lot about how theater is an event that takes place in space and time. There is a lot that can be done on Zoom, but it’s different in person,” said McKittrick.

Warming up.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

The instructors also wanted students to experience that energy and feel empowered to pursue creative projects, regardless of concentration or background in theater. The final assignment is a creative pitch for a new musical or revival on any subject.

Chinaza Asiegbu ’22, a history concentrator, welcomed the chance to use her academic work on African liberation and postcolonial history as a foundation for hers. Though she hasn’t decided on a pitch yet, “a work that represents those issues would be so powerful in the theater,” said Asiegbu. “This class has taught me that theater is for everyone. It’s an ongoing, inclusive conversation. So someone like me who does research on history has a vital place in the theater and that story to tell.”

“The purpose of a liberal arts university like Harvard is to expose every student to the humanities,” added Paulus. “It’s been my dream that every student at Harvard graduates with an experience of the arts. This class is one opportunity for students to approach their learning from an artistic point of view.”