Their assignment? Design a more equitable future

Students reimagine uses for public land after Biden vows funds to redress harms done to urban areas when highway system was built

Students in Daniel D’Oca’s fall studio examined injustices created by U.S. interstate highway system.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

The assignment wasn’t simple, but it was relevant: Find ways to help communities around the country address racial injustice created by the nation’s biggest infrastructure project — the U.S. interstate highway system.

“No other policy shaped the built environment in the U.S. more than the Interstate Highway System. I’m in awe of it in many ways. But its influence wasn’t all, or even mostly, good,” said Daniel D’Oca, an urban planner and associate professor in practice of urban design at Harvard Graduate School of Design, who led a fall studio for students to reimagine how public land might be used if the highways were removed or relocated. The exercise was inspired by President Biden’s pledge to set aside funds from the Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act to redress the harm done to communities of color by federal public works projects.

Launched during the Eisenhower administration, the U.S. interstate highway initiative added close to 50,000 miles of new roads in about two decades, speeding travel and the transport of goods, boosting auto sales, and ushering in the era of suburbia. But it came at great cost to the environment, to public health, and to Black, Latino, Indigenous, and low-income neighborhoods that were targeted for clearance or split by highway planners.

Residents lost homes and businesses, churches, and parks to freeway bulldozers. Neighborhoods were divided or sheared off from the surrounding community by multilane highways, decks, and ramps, further depressing property values. The roads meant more people spent more time in cars, releasing more pollutants into the environment and worsening asthma and other negative health effects, particularly for those who remained in more congested urban neighborhoods.

Working with liaisons in a dozen U.S. cities, students reimagined how sections of the interstate system that had been a source of harm could become a community benefit. Students engaged with neighborhood, community, and civic groups, along with city and state officials, to anchor the designs in local priorities and better grasp the complexities of public works funding.

In addition the class visited several cities, including Boston and Portland, Maine, to examine projects underway and learn how local officials had resolved various challenges. Students toured a local success in Jamaica Plain with community advocates — the restoration of part of famed landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace of parks and greenways and reconfiguration of the crossroads at Forest Hills that followed the state’s removal of the Monsignor William J. Casey overpass in 2015.

Students visit Boston to study a finished redesign project, the removal of the Casey overpass at Forest Hills.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

In December, students presented their designs to a 14-member panel of academic critics.

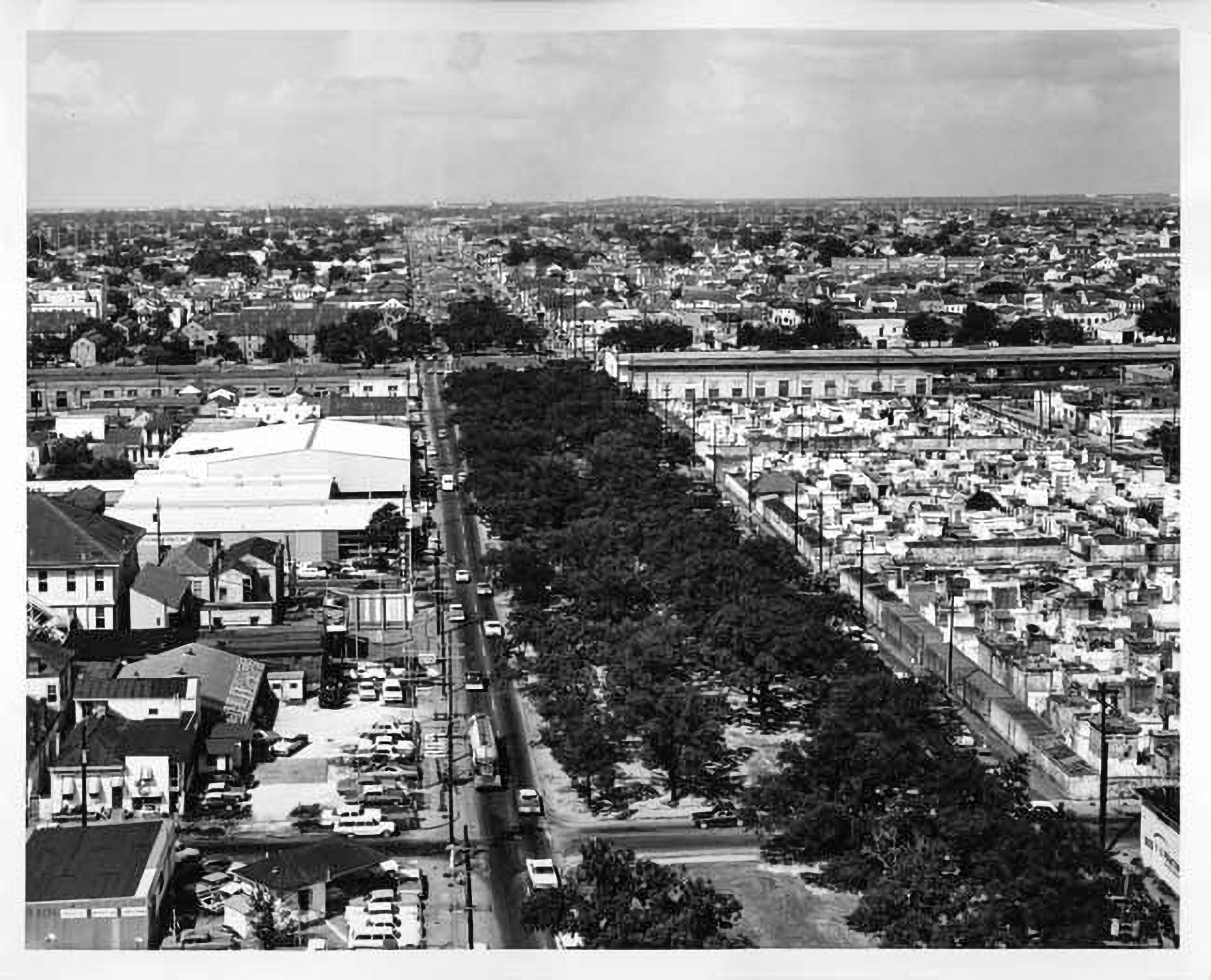

One involved Interstate 10, which ripped through the heart of New Orleans’ historic Tremé district when it was constructed in the late 1950s. Singled out by Biden, it’s perhaps the best-known example of the discriminatory effects of many public works projects. The highway deck was erected over Claiborne Avenue, Tremé’s main thoroughfare and a once-thriving Black neighborhood and commercial center with a rich musical and cultural legacy that was mere feet from homes and businesses. The deck was built with little regard for the damage it would do to the community and its residents.

Photo from 1968 shows Claiborne Avenue before expressway was built over it, ripping up oak trees and tearing apart the thoroughfare sometimes called the “Main Street of Black New Orleans.”

Courtesy of the New Orleans Public Library/Photograph by Joseph C. Davi; AP file Photo/Gerald Herbert

“So much of our project was thinking about how the highway can mediate the different memories associated with it, the trauma associated with the highway, and also trying to use that infrastructure as healing,” said Darien Carr ’17, M.Arch I ’23, and Marina DeFrates, ’17, M.Arch I ’23.

For years, debate roiled over what to do about the rusted-out highway deck, pitting residents against political and business interests and resulting in little except hard feelings. But its poor condition, the danger it poses to drivers who have nowhere to pull over safely during a breakdown or traffic stop, and the prevalence of drive-by shootings, along with the draconian eminent domain takings that repairing the deck would require, turned public sentiment in favor of removal.

Much of the students’ research and work with liaison Amy Stelly of the Claiborne Avenue Alliance involved understanding the area’s complicated history and culture so their proposal, which they called “Thirdline” as a playful nod to New Orleans’ famous parade tradition known as the Second Line was grounded in the community’s priorities.

“Culture, regardless of whether you’re in New Orleans or New York, has to be fundamental to the idea. It has to be a big consideration. Otherwise, it’s not going to be accepted.”

Amy Stelly of the Claiborne Avenue Alliance, a community organization pushing for removal of I-10 overpass in New Orleans

“Culture, regardless of whether you’re in New Orleans or New York, has to be fundamental to the idea. It has to be a big consideration. Otherwise, it’s not going to be accepted,” said Stelly.

Despite near-consensus that the interstate deck no longer served the city well, Carr and DeFrates could see that with politically connected development interests sited along the deck and many buskers and Carnival krewes assembling under it because it follows the Mardi Gras parade route, simply proposing a removal was not necessarily the best approach.

Instead, they offered several proposals, ranging from completely removing the deck to keeping fragments as historic markers or repurposing them, and then recycling demolished materials into community amenities like multi-use paths with permeable paving.

“I think for Marina and I, it was important that we were engaging and that this didn’t become a project that was just an architecture project about the aesthetic and design, but was rooted in these very real concerns of memory, but also feasibility and the real-life context,” said Carr.

Sai Joshi (far right) pivoted from highway removal and redesign to climate-resiliency planning while rethinking Interstate 35 in Duluth, Minnesota.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Seeing the challenges that climate change presents to urban planners, Sai Joshi MAUD ’22, was intrigued by Interstate 35 in Duluth, Minnesota. With its proximity to Lake Superior and low population density, Duluth has attracted media attention in recent years for what some believe is its potential as a refuge from rising temperatures brought about by climate change.

The highway cuts through the downtown, adding heavy emissions and traffic to Duluth’s most populous area, and residents say it forms a physical and psychological barrier that makes it more difficult to navigate around the city and limits access to the lake, Joshi said.

While there was general support for removing the highway deck, several obstacles soon emerged. Local transportation officials worried that redirecting vehicles through the city would create traffic volume; the land where the deck once stood would require significant rezoning before it could be redeveloped; and most troubling, frequent stormwater surges from Lake Superior sometimes caused flooding.

Joshi had to pivot from highway removal and redesign to a reconsideration of the city grid and its relationship to the lake — in effect climate-resiliency planning.

“All of this land … is suddenly going to be filled with water. What is that going to look like? How do I make these connections? That is still a challenge,” she said.

It’s something Joshi wants to continue exploring in the future. “I think so many cities, especially coastal cities across the world, are going to face this challenge. Living with water is going to be one of the many realities that require restorative solutions for mitigation or adaptation.”

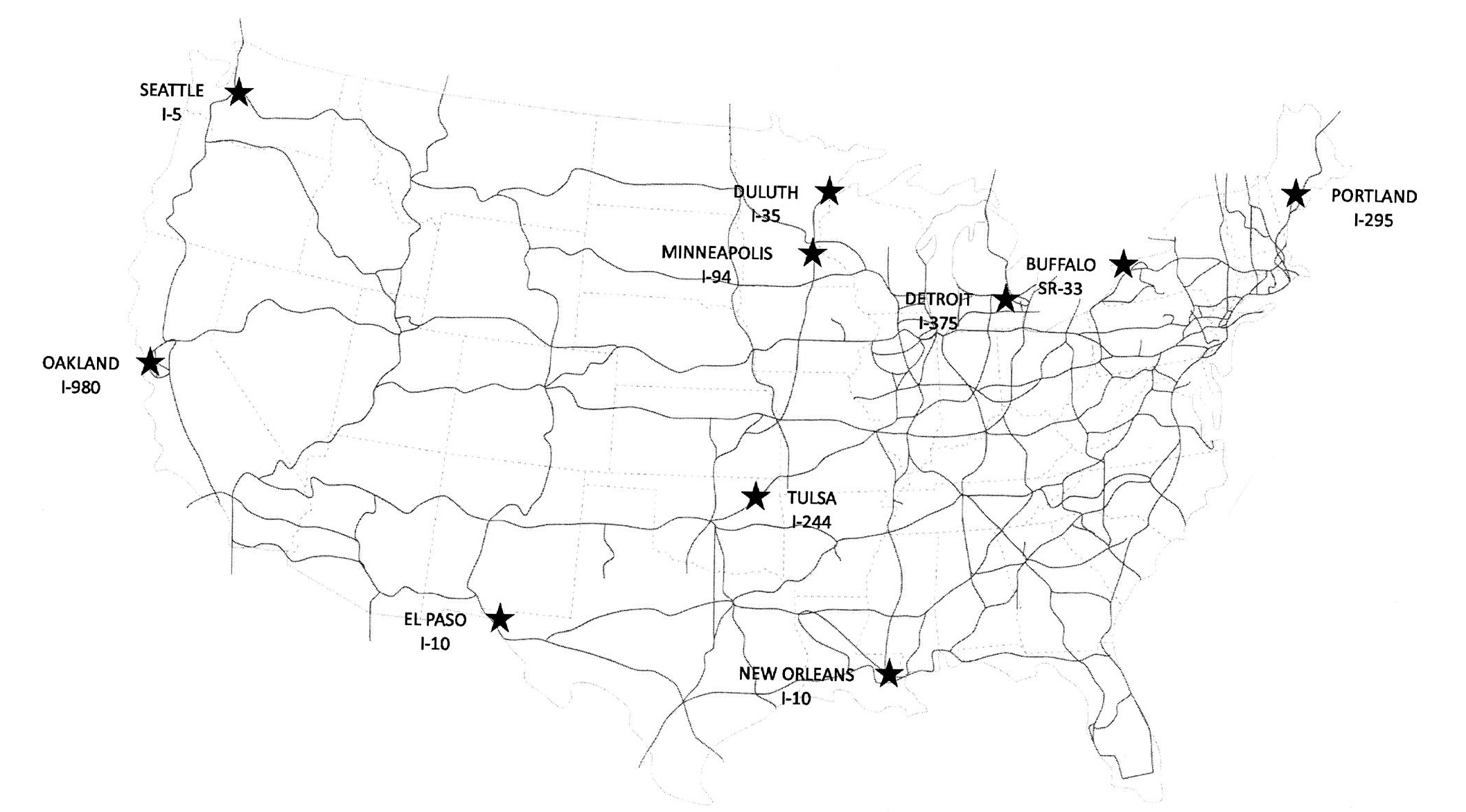

The class reimagined highways in 10 cities.

Courtesy of Daniel D’Oca

When New York state highway 33 was built between 1957 and 1971, it divided downtown Buffalo in two, separating the city’s largely Black population on the east side from its predominantly white residents on the more affluent west side. The project forced 600 Black families out of their homes and paved over a historically significant green space designed by Olmsted and his partner, Calvert Vaux, in the late 1800s.

The highway project not only seized property by eminent domain, greatly reducing what displaced owners were paid in exchange, it eliminated much-needed housing for thousands of Black residents who had few places to go because of redlining, limited economic resources, and job mobility.

Though New York state allocated $6 million for an initial study and site design in 2016 to consider redirecting the highway, which is in a below-grade, open-air trench, or putting a cap over it, Xiaoji Zhou, MLA II/MDes ’22, said it’s not clear how much work has been completed.

But Zhou said it became very clear in talking to different constituencies that no consensus had yet developed on what should be done with the 14 acres of former green space. The most organized and vocal advocates were pushing to restore Olmsted’s tree-lined lawn, but the cost and geography limitations, regulatory requirements, and civic obligation to serve a diverse array of modern uses makes a true Olmsted restoration unlikely.

Locals involved for decades told Zhou how difficult it has been to reach out to the broader community to build support for various ideas.

“Even though they’re making progress, a lot of people — like those born after the expressway had been completed — had no vision for what a parkway could be, so it was hard for them to envision why we need to put it back,” she said.

To overcome this common planning hurdle, Zhou designed and built a community engagement tool where, like a game board, stakeholders can assemble and reassemble color-coded blocks that represent different elements of a potential project. The city of Buffalo plans to use Zhou’s tool for its continuing work on the highway project.

“As designers and planners, we too often assume that creativity and reality are at odds … I think these students demonstrated that this isn’t the case,” D’Oca said.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The project also brought forward issues Zhou hadn’t anticipated. Some members of the community, including the Black American Chamber of Commerce, were in favor of restoring the Olmsted parkway in hopes that it would raise property values and benefit homeowners who have had to live for decades with a highway 200 feet from their front doors. Given the park’s important legacy, restoring it seemed like the obvious, most desirable outcome, at first.

But it could lead to the negative effects of gentrification, as research shows that sharply rising property values often make an area prohibitively expensive for Black homeowners and residents, forcing them to sell or move, Zhou noted.

“But then I realized it’s not only about bringing back part of the history,” she said. “It’s more about, how do you really strengthen a community nowadays?”

For D’Oca, the students successfully generated ideas that were “big, bold, and long-term,” but also “sensitive and responsive” to a community’s needs.

“As designers and planners, we too often assume that creativity and reality are at odds: that accommodating community preferences restrains creativity and undermines good design” he said. “I think these students demonstrated that this isn’t the case. I was really impressed with their ability to digest the sometimes-conflicting feedback they received … and create visions that are enticing to people in and out of Gund Hall.”