A musical duo of mythic power

Harvard’s Spalding helps jazz legend Wayne Shorter turn ‘Iphigenia’ into opera

The source material may be ancient, but jazz legend Wayne Shorter’s new opera, written in collaboration with Esperanza Spalding, a Harvard professor and Grammy-winning bassist-singer, looks to the future, not the past.

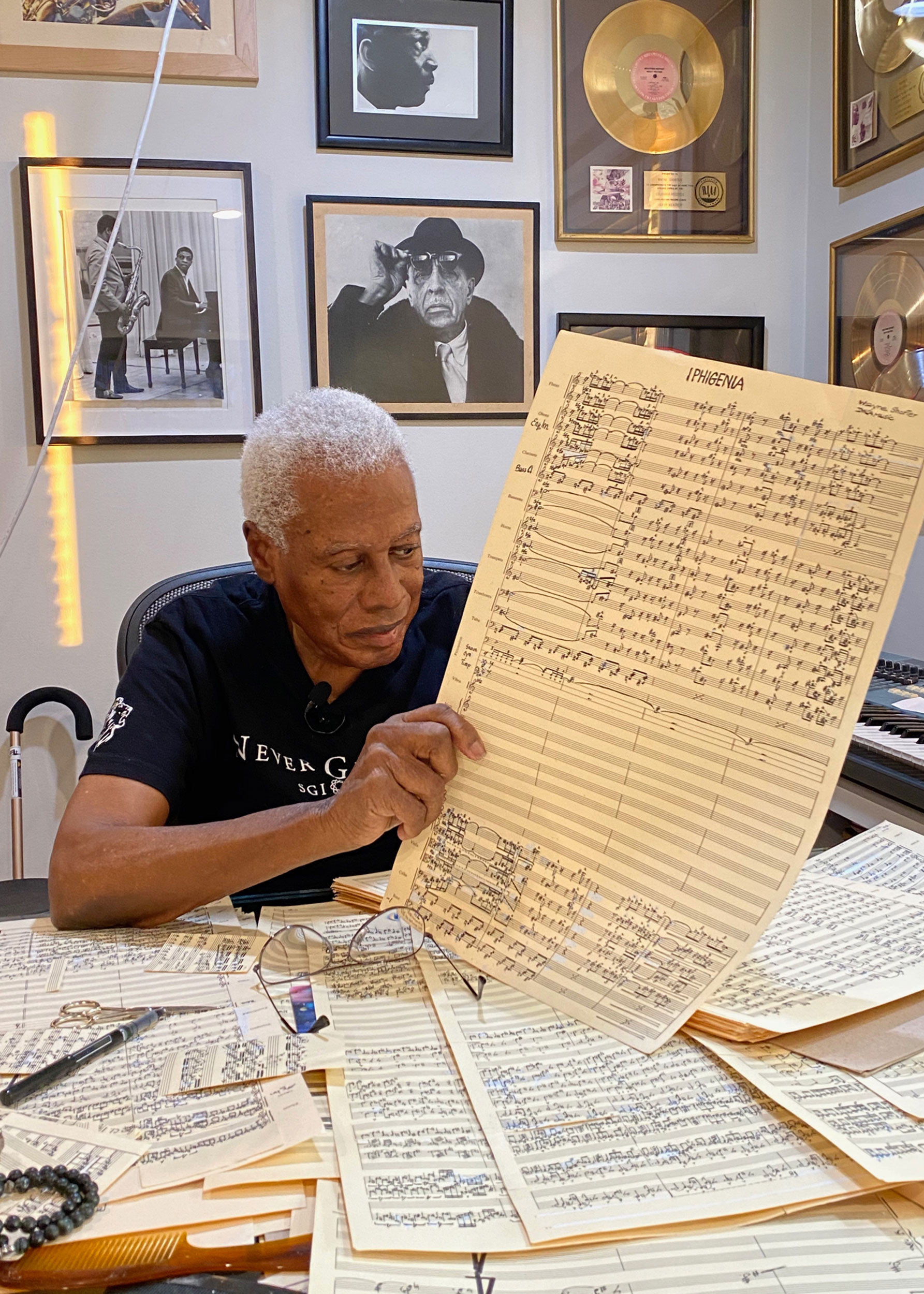

“Iphigenia,” a project Shorter began thinking about in the 1950s, is a bold reimagining of the classical figure, daughter of King Agamemnon and Queen Clytemnestra. Spalding wrote the libretto for the show and is performing in it. The renowned architect Frank Gehry, who has studied and taught at Harvard, designed the sets. Eight years in the making, the opera made its worldwide debut Nov. 12 in Boston.

Shorter, 88, is a trailblazing composer and saxophonist who first made his name as principal songwriter for Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers in the 1950s and played in Miles Davis’ second classic quintet. In 1971, he formed Weather Report, which pioneered the avant-garde style known as jazz fusion.

Shorter and Spalding spoke to the Gazette about their collaboration. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Wayne Shorter and Esperanza Spalding

GAZETTE: What made you decide to finally take this project up after so many years?

SHORTER: It was always in the back of my mind. I don’t like things undone. And especially with this, it’s like a road sign in my life. It’s a road sign about what encompasses my mission for living while living. What is the mission? What’s involved with my mission?

GAZETTE: What inspired you to get on board with this project? Did you find the prospect of writing the libretto to an opera Shorter has been thinking about for 60-plus years at all daunting?

SPALDING: In terms of living up to, I had to put that down a long time ago. The music itself, and just Wayne’s mysticism and spirit and creatorship — it’s so profound. He’s an anomaly. So, I think those of us who get the privilege of working with him, we give up the idea of “matching.” It’s more like, how can I be reflective to the majesty and the beauty of what he’s offering?

In this case, I wasn’t originally slated to be librettist. I was just helping Wayne connect with people that I thought could help get his opera made. Over time, I became a part of the producing team and was looking at other writers, thinking about who could be a good fit for him, people who understood the significance of him as a creator. Then his partner, she kept telling me “Wayne really wants you to write it.” I was like, “Oh, no, no, no. No way.” I guess I just gave in. I was like, “Well, I have to trust his opinion.”

I’m blessed by the work, blessed by this opportunity. But it is really daunting to craft narrative shape when the music already exists. He had written all of the music, so it was a really a dance of learning to surrender what I thought it was going to say next, and hearing what the music seemed to be saying or portraying, and letting that inform how the narrative unfolded. I will say that the way that our story moves is totally informed by the way Wayne wrote. Since this is the music, what story is being told here in this context of Iphigenia? That’s really how the narrative arc took shape.

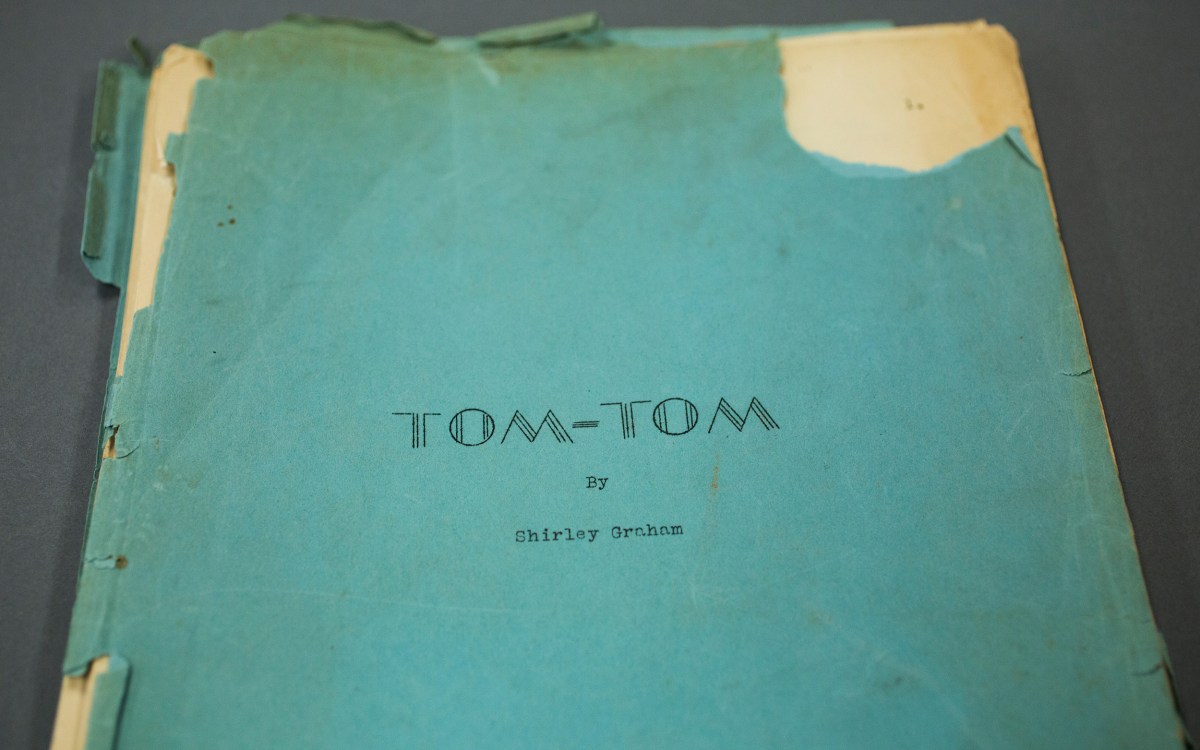

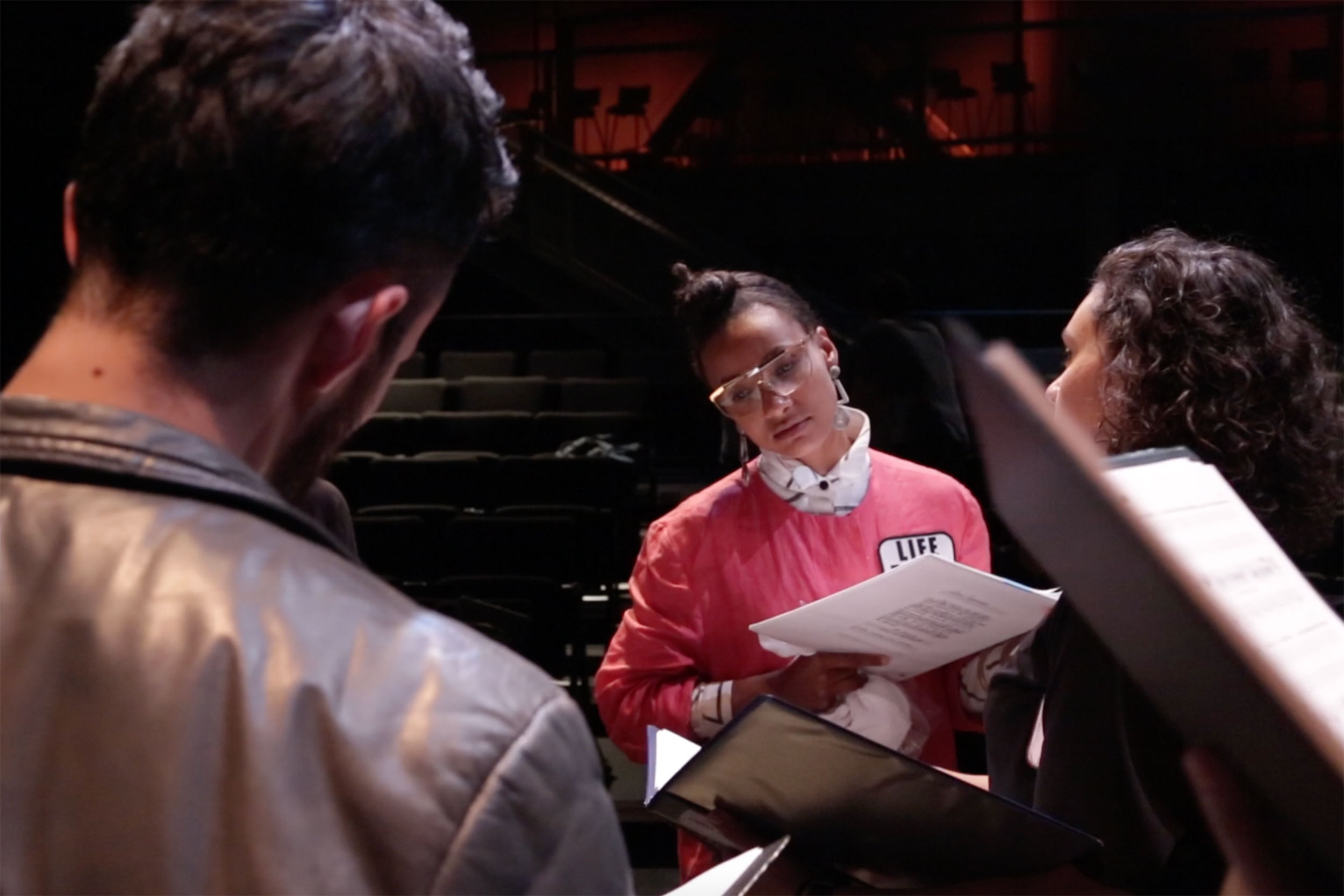

Wayne Shorter with the score for “Iphigenia,” and Esperanza Spalding in a huddle.

hoto of Shorter by Jeff Tang; photo of Spalding courtesy of Real Magic

GAZETTE: How familiar were you with the Iphigenia story?

SPALDING: I didn’t know or care about Iphigenia. And then, of course, the way that Wayne pitched it, the way that he spoke about the character, I was like, “Damn, she sounds interesting.” So I started reading translations and analyses. I’m not finding the character, but feeling little hints, little allusions to what this character signifies. And then, one day, I was like, “Oh, these stories were all written by men about this woman figure.” So, of course, she’s eluding the grasp of my appeal to connect with her and meet her because she doesn’t exist! She’s a character, she’s an expression of the human psyche as understood by the men who’ve been writing her throughout history. In recent years, there have been more iterations and translations of her, but we have to remember that she’s traveled on through history predominantly through the minds and mouths and hands of men.

GAZETTE: You workshopped some of the libretto at Harvard with the musicologist Carolyn Abbate. Tell me about that.

SPALDING: First of all, I was like, “How am I going to really bring forth this libretto and give it the energy that it needs right now and teach two courses?” I was kind of in crisis mode leaning into spring 2020. And I had been sitting in on Carolyn Abbate’s lectures about opera and just sitting with her to discuss the project itself and share with her where I was at and the concept. Then it just kind of struck me and I pitched this idea to her: What if we make a lab that invites students who are passionate about opera, who are passionate about theater and writing, to dive into a process with the same basic ingredients that I am confronted with, and I can share with them how my development process is taking shape, and reflect on and be like a co-explorer as they take a similar journey. And she thought it was a cool idea and then we co-led or — I don’t like the word teach — but we co-curated that lab and through the course of that lab, I was able to finish the libretto. There really was something about dissolving the “I’m a singular writer voice holed up in my little writer’s room trying to solve this.”

“It was like kids on the playground; finding a lot of gratitude within each other for doing what we’re doing, doing it sort of fearlessly and not getting in the way of the discovery.”

Wayne Shorter

GAZETTE: You’ve worked with Esperanza before, but this project took eight years to complete. Tell me about this collaboration. For some of it, you were both living at architect Frank Gehry’s home in Santa Monica, and for other parts, you were on different coasts. What made it work so well?

SHORTER: We didn’t come together with the idea of assessing if something worked, if it had worked. We both shy away from that word “work.” It’s kind of mechanical. It’s some sort of gamble where you negate yourself completely from what’s going to transpire. So, we would say, “Let’s see what happens.” We’re still in charge of “what happens.” Not in charge, but we have some say in it.

It was like kids on the playground; finding a lot of gratitude within each other for doing what we’re doing, doing it sort of fearlessly and not getting in the way of the discovery.

GAZETTE: What are you hoping audiences will take away from the show?

SHORTER: It would be nice if the audience would consider themselves to be enfolded in an unfolding and welcomed.

SPALDING: I feel that all of this work is really just to make a kind of portal or access point to the music that Wayne wrote. And if we do our job well, everyone in the room, or anyone who wants to have that kind of experience, will feel their own sense capacity for beauty and death and poetry activated and titillated and stretched. I feel that’s really the purpose of the work. Everything that could be said has already been said at some point along the way on this human journey. So it’s not about “Oh, I want them to get the message” or “I think we nailed it.” It’s more like, “I want this to be radiated into the world and, and made available for people to experience.” And I know that’s gonna happen, so I feel we’re already moving in the right direction.