The Center for American Political Studies’ post-election round-up included Harvey Mansfield with wife Anna, (clockwise from upper left), Jim Ceaser, William Galston, and Bill Kristol.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Could a divided government be what the voters want?

Speakers at events suggest it could lead to more constructive balance of power

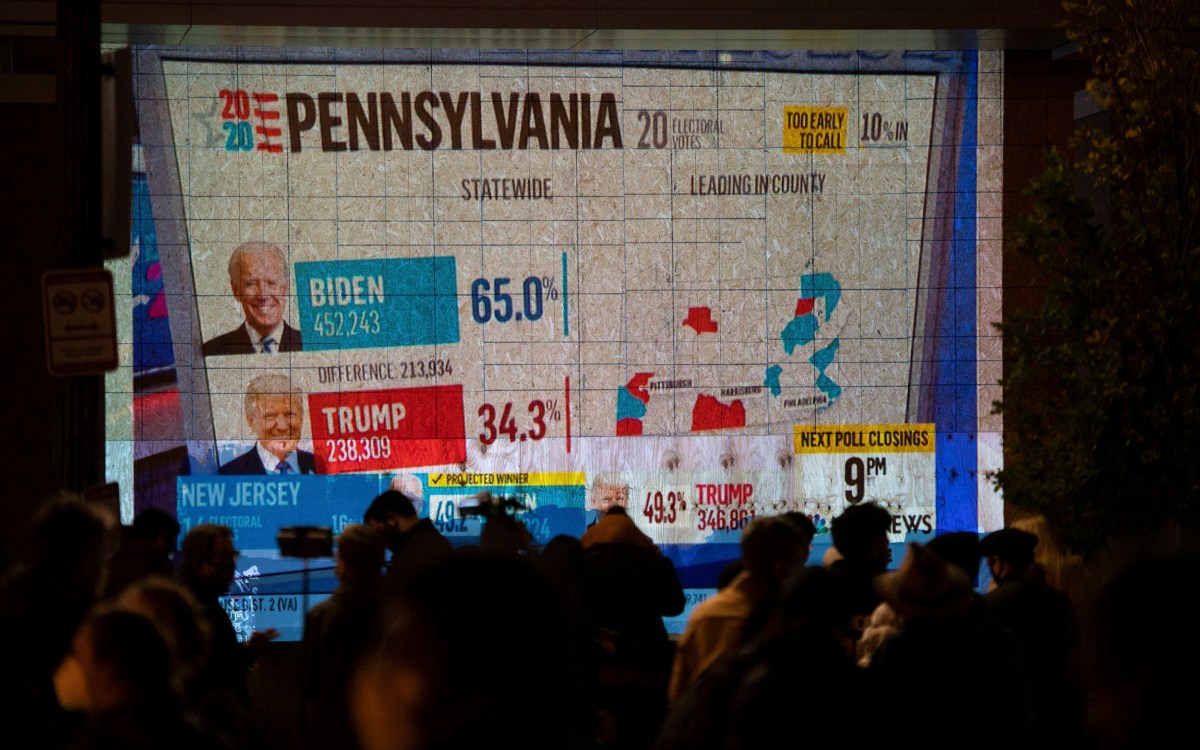

It was a hotly contested election that went down to the wire and produced a shift at the top, with Democratic former Vice President Joe Biden as the president-elect and the historic selection of Senator Kamala Harris as the first woman and first woman of color to be vice president-elect. But it was apparent fairly soon after Election Day that the results would fall short of the takeover the Democrats sought, and some pollsters predicted. The party kept control of the House of Representatives but lost a number of seats, and it posted gains but failed to win a majority in the Senate. Overall, arguably closer to status quo than resounding repudiation.

The mixed results, however, may signal a desire by Americans for a more constructive balance of power and cooperation in government, hinted panelists at events on the lessons from the election held by the Center for American Political Studies (CAPS) at Harvard University and the Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics (IOP) on Thursday evening. Many of the speakers, drawn from both sides of the aisle, offered hope that the two parties could find more areas of common ground in the future.

Those ideas emerged from some unlikely allies. Speaking at the CAPS round-up were William Kristol, a conservative pundit and former Vice President Dan Quayle’s chief of staff, and William A. Galston, a top aide to former President Bill Clinton. Both agreed that as a personable moderate, Biden represented the Democrats’ best chance to win the presidential race, offering an acceptable option to Republicans seeking an alternative to the divisive President Trump and the overall promise of greater unity to a nation grown weary of winner-take-all politics.

Kristol, editor-at large of The Bulwark, was the first to air this opinion at the event, which was sponsored by the Program on Constitutional Government. But during his opening remarks in the 15th biennial election debate between the two, Galston, who served as a deputy assistant for domestic policy to Clinton and is currently the Ezra K. Zilkha chair and senior fellow of the Brookings Institution, repeated it — and noted that he had made the same pronouncement verbatim on a podcast earlier in the day.

Bill Kristol was the first to air his opinion at the Center for American Political Studies event. Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photogra

For much of the 2½-hour event, the longtime sparring partners seemed to agree more than disagree. In fact, the strongest opposing view was taken by the panel’s third speaker, University of Virginia Harry F. Byrd Professor of Politics James W. Ceaser, Ph.D. ’76.

Despite their traditional, if friendly, antagonism, Kristol and Galston both saw the selection of Biden as a positive move. Kristol called the president “a demagogue,” noting “demagogues are dangerous,” while Galston called for the return of “a great American middle.”

“The literal Trump position is ‘Stop the count,’” referring to one of the president’s tweets. “That’s an astonishing view for a politician, more astonishing still for a president.”

William Kristol, editor-at large of The Bulwark

In regard to the mixed elections results, Kristol observed, “The public reacts against overreaching by putting the other party in control of whatever branch. They have a chance to do the House or the Senate or sometimes the presidency.”

Ceaser, on the other hand, took a much harder line, noting what he called “the outbreak of chaos in the streets,” referring to violence that erupted at some Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of a series of high-profile police killings of African Americans earlier this year.

“What centrist Democrat has had the courage to speak out against it? Trump at least is taking a stand in protection of law and order,” he said.

Kristol rebutted that view. The founder of the now-defunct Weekly Standard said Biden had, in fact, spoken out against violence, including the looting that followed some of the demonstrations. This was in stark juxtaposition, he said, to Trump’s failure to denounce “threats of violence and acts of violence on his side.”

“I’m looking forward to all the conservatives being equally concerned about two [newly elected] Republican members of Congress, fostering QAnon conspiracies and unhealthy growth of conspiracies and bigotry,” he said.

Kristol also differentiated between Trump’s call last week to stop tallying votes and the GOP’s call to end the recounts in Florida during the 2000 George W. Bush-Al Gore election, which he called “defensible.”

“The literal Trump position is ‘Stop the count,’” he said, referring to one of the president’s tweets. “That’s an astonishing view for a politician, more astonishing still for a president.”

The “radio silence” of the majority of GOP legislators at this Trump demand “raises the question of where the party goes after Trump,” said Kristol.

He asked: “Once he’s out of office, how strong is he?” Kristol answered his own question by noting Trump’s prevailing influence on down-ballot races and musing on how it is likely to diminish over time.

The Institute of Politics hosted a virtual panel of top political strategists including Mark D. Gearan ’78 (clockwise from top left), moderated the discussion among Scott Jennings, Maya Rupert, Karen Finney, and Robby Mook. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard University

More like this

Among the changes the election has brought, said Galston, is the national picture. “The rumors of rising Democratic competitiveness in the South and Southwest were not exaggerated. Changing demography has a lot to do with that,” he said, even as he noted, “Texas is still several political cycles away from real competitiveness.”

Both Galston and Kristol agreed that the federal government has ceased to function as it was designed to, with too many decisions made by presidential executive order. “Politics, like nature, abhors a vacuum,” said Galston. The situation won’t be remedied, he said, “until we have a functioning Congress again.” Kristol agreed, “We don’t have budgets; we don’t have hearings. That horse-trading was necessary.”

Ceaser, meanwhile, argued that intolerance on the left bore some responsibility for the country’s divisiveness. “At the university level you see a systematic denial of liberal values,” said Ceaser, citing “relentless attacks on liberalism from the left” and left-wing “armed mobs.”

His co-panelists held much more measured views of both sides. More hopeful ones, too. “Maybe with Trump removed you can have more ferment in the Republican party,” said Kristol. “Biden and [Senate Majority Leader] Mitch McConnell have worked together,” he added, with guarded optimism. “They’re old pros. Maybe we see them compromising.”

A similarly optimistic note was sounded by Galston, as he answered a question about how Florida could both vote for Trump and approve raising the minimum wage to $15. “There is an American center, an American majority, that has a sense of equilibrium,” he said.

Political rivals also found common ground at the IOP panel “Election 2020: What Just Happened?” Moderated by IOP Director Mark D. Gearan ’78, the hour emphasized ways that the two parties might go forward.

“I’ve heard people say that we are more divided than ever,” said Scott Jennings, McConnell’s senior adviser, Zooming in from Kentucky. “But maybe this election is exactly what voters demanded, with neither party having too much control. Maybe we’re actually more united, in that we want to see the two parties working together. Regardless of our battle scars, maybe this is a way to reshape what we’re doing.”

Biden’s supporters, he said, could learn from gains Trump made during his presidency. “If you look at the Republican policy agenda under Trump, it wasn’t all that unpopular,” Jennings said. “We’re now seeing the repudiation of a messenger, but not the repudiation of an agenda.

“[Republicans] have far more African Americans and more Hispanics than we had in 2016. One thing you may see as an outgrowth of Trump is that the Republicans bill themselves as the party of the working class and run against Democrats as the party of the ruling class.

“What we needed was more people engaged in democracy, and we got that. What we need to learn now is acceptance: There were a lot of people who never accepted Donald Trump. And now there are people who have to learn to accept Joe Biden.”

Karen Finney, who was senior adviser for communications and political outreach for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign, concurred that Trump’s campaign was connecting in Black strongholds, and credited Biden with toughening up his message accordingly.

“One thing I’ll give the Biden team credit for: They picked up sooner than we were able to that … with Black men, part of what was resonating about Trump … was an issue around taxes. And sort of what I would call ‘toxic masculinity,’” Finney said. “He doesn’t take any guff, and he says what he means. They caught onto this early enough to make some shifts in their messaging and to really speak to Black men.”

Finney said that a divided government may indeed present possibilities for more bipartisanship. But that puts a greater onus on voters. “We have to hold them accountable. We have to ask for the receipts next time the election comes to say, ‘Did you get done what I elected you to do?’ And I think that in this kind of divided government this outside pressure from a lot of organizations can be very important to create the pressure on members of Congress of both parties.”

Robby Mook, the campaign manager for Clinton’s 2016 campaign, said one of the takeaways from this election involves the loyalty Trump seems to command. “The more I do this, the more I think that this stuff is personality-driven. Ideology matters, but look at Trump: He is ideologically all over the place, but people were still drawn to his personality. So the real question in the next presidential election may not be about policy, but who do people want to rally around as a person?”

Mook also named a notable similarity in the 2020 and 2016 elections: In both years, the polls proved unreliable. “Watching the results come in, it was really feeling like déjà vu all over again. As we begin to strategize for the midterms, it may be time to look at the toolbox we have and whether it’s really working or not.”

Although Thursday’s panels were scheduled for nearly 48 hours after polls had closed, they still had to contend with the absence of definitive results. As Maya Rupert, campaign manager for Julián Castro’s 2020 presidential campaign, noted at the IOP event, this kind of uncertainty is something to which voters must begin to accustom themselves.

“That’s my big takeaway: The country is past the point where election night is going to bring that moment of certainty,” she said. “It is dangerous for us to continue to have that expectation.

“We need to wrap our heads around seeing election night as the start, not the finish.”