The life and legacy of RBG

Harvard community reflects on Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a trailblazing, tireless fighter for rights

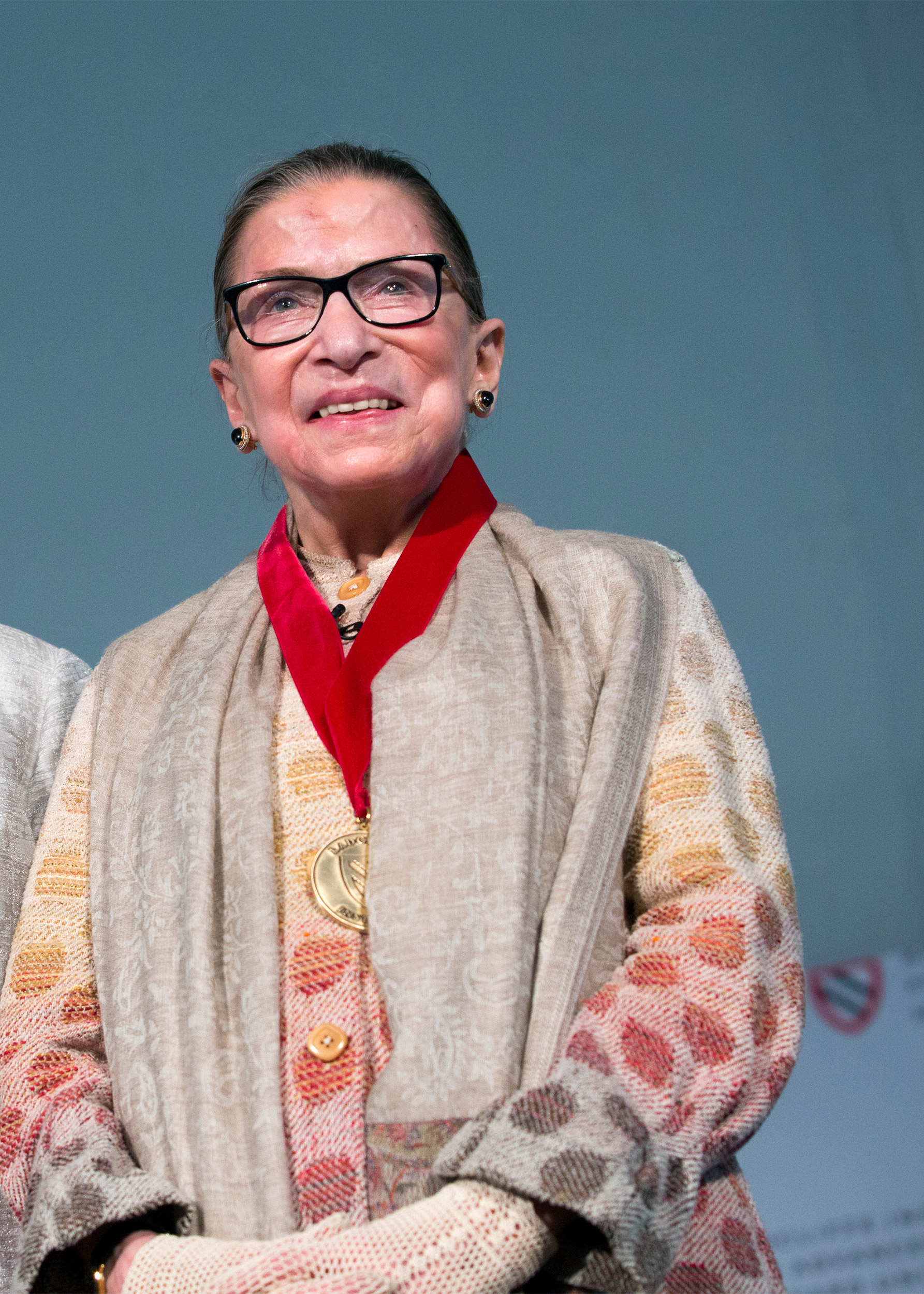

Ruth Bader Ginsburg was awarded the Radcliffe Medal in 2015.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

A champion of race and gender equality. A pioneering lawyer on women’s equality. A civil rights hero. A feminist symbol. A major pop icon. Notorious RBG. A key justice on the nation’s highest court.

As the country grieves the loss of U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who died Friday at 87, thousands gathered near the steps of the Supreme Court building to pay homage to her life and her contributions to American jurisprudence and women’s rights. Ginsburg received an honorary degree from Harvard in 2011 and the Radcliffe Medal in 2015. To understand her legacy better, we asked members of the Harvard community to reflect on what she stood for and how she will be remembered. Here are their thoughts.

Tomiko Brown-Nagin

Dean, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study,

Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law, Harvard Law School

Professor of History, Faculty of Arts and Sciences

Ruth Bader Ginsburg will be remembered as a champion of equality. Well before she ascended to the Supreme Court, Ginsburg had left an indelible mark on law and society. At the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, she was the chief architect of a campaign against sex-role stereotyping in the law, arguing and winning five landmark Supreme Court cases during the 1970s. These decisions established the principle of equal treatment in the law for women as well as men and banished numerous laws that treated men and women differently based on archaic gender stereotypes. Her achievements as a litigator made her, as many have said, the Thurgood Marshall of the women’s rights movement.

As an associate justice on the court, Ginsburg wrote opinions that championed both gender and racial equality. Most notably, in United States v. Virginia — the culmination of her campaign for equal treatment in the law — her majority opinion held unconstitutional the Virginia Military Institute’s practice of excluding qualified women from admission merely because of sex. Her oral dissent in Ledbetter v. Goodyear, which rejected a pay discrimination case on a technicality, pushed Congress to enact and President Barack Obama to sign equal pay legislation in 2009. She defended women’s reproductive freedom in several cases and supported gay marriage. Through her stinging dissent in Shelby County v. Holder, the 2013 decision that gutted the Voting Rights Act of 1965, she captured the imagination of a new generation. Her new admirers, praising her fierceness, deemed her the “Notorious RBG.” In other cases, Ginsburg defended affirmative action against a legal onslaught, and she poignantly noted in interviews that she and many other women had benefited from the practice.

Her legacy, however, goes far beyond what she achieved in court. Ginsburg also should be remembered for her resilience. Personal setbacks animated her quest for social justice. She memorably summed up the connection between her personal losses and her public life at a Federal Judicial Center conference that I attended years ago. Profound challenges — the loss of her mother the day before she graduated from high school, her husband’s struggle with cancer while they were both in law school — fueled her fierce determination to accomplish her dreams and achieve justice for others. “I wasn’t going to just sit in the corner and cry,” I recall Ginsburg defiantly noting during her talk. Those words have stuck with me all these years. Ginsburg’s refusal to crumble into a heap of defeat is a defining and inspiring part of her legacy.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg receiving her honorary degree after Plácido Domingo (right) sang to her at Harvard’s 2011 Commencement.

Brooks Canaday/Harvard file photo

Carol Steiker

Henry J. Friendly Professor of Law

Special Adviser for Public Service, Harvard Law School

Almost a decade ago, Ruth Bader Ginsburg received an honorary degree from Harvard, joining a star-studded list of other luminaries being similarly honored that day. As each honorand was called up to receive a degree from then-President Drew Faust, the crowd responded with warm appreciation. Plácido Domingo, the famed opera singer; Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, president of Liberia and the first woman to lead an African country; Timothy Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web; Dudley Herschbach, winner of the Nobel Prize in chemistry — each received enthusiastic applause and even pockets of standing cheers. But when Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s name was called, the entire Tercentenary Theatre erupted into a massive, thunderous standing ovation. And when Ginsburg descended from the stage at the end of the ceremonies, people scrambled to the aisle to try to snap photos or to touch the sleeve of her robe as she passed.

Many famous and accomplished people have been honored at Harvard’s graduations, including a number of Supreme Court justices. But this was different. Ginsburg would not be dubbed “Notorious RBG” for another two years, but she was already an icon. Why? Not merely for her important work on the nation’s highest court, but also for her trailblazing work in an era when female attorneys and legal rights for women were both depressingly few and far between. The story of Ginsburg’s tremendous successes as a young civil rights attorney who litigated the key cases establishing women’s constitutional right to equal treatment has been well-told in the documentary “RBG” and the biopic “On the Basis of Sex.” But our familiarity with that story does not make it any less amazing or improbable. The world will never be the same.

Martha Minow

300th Anniversary University Professor,

Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor

Member of the Faculty of Education

Very few individuals in history come close to the extraordinary and significant role played by Justice Ginsburg in the pursuit of justice before she joined the bench. She would be a landmark figure just by being the first woman to earn a tenured faculty post at Columbia Law School. And she made history as director of the Women’s Rights Project of the American Civil Liberties Union, argued landmark cases on gender equality before the U.S. Supreme Court — brilliantly crafting successful challenges to the system of legally enforced gender roles that limited opportunities for both women and men. With vision and brilliance, she earned a place in the history books and on the honor roll of civil rights heroes.

Then, as judge on the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, she demonstrated the highest level of legal craft in crucial decisions. And as associate justice of the Supreme Court, she has produced a body of superbly crafted opinions, building on precedent while always demonstrating that law is meant to — and with conscientious work can — serve justice for real people.

When she was a student at Harvard Law School, she faced a class of over 500 men and only seven other women. She juggled her roles as a wife and mother with her work as a law student and faced a dean who chided female students for taking the places of qualified males. She excelled. She joined the Harvard Law Review. When her husband, fellow law student Martin Ginsburg, had to deal with cancer, she took notes for him and helped him recover. And when the Harvard dean refused her request to earn her degree while moving to New York with her family and completing her final year of schooling at Columbia Law School, she transferred there and promptly rose to the top of the class.

She gently but rightly resisted the requests of later Harvard Law School deans to accept a tardy degree from Harvard Law School. Finally, in 2011, she received a Harvard degree — an honorary doctorate, the University’s highest academic honor. In celebration, an opera singer — and fellow honoree — sang for her and the assembled crowd.

I am one of countless people she directly encouraged and deeply inspired to use reason and argument in service of justice and humanity. Justice Ginsburg also showed that it is possible to build deep and meaningful friendships with people despite severe disagreements. At this time of deep social and political divisions, there is much to learn from her life and her commitments. Above all, she changed the lives of millions as a lawyer and as a jurist by dismantling barriers to employment, education, and roles in families and society based solely on gender — and showed how law can, with persistence and vision, be a tool to bend the arc of the moral universe toward justice.

Susan H. Farbstein

Clinical Professor of Law, Harvard Law School

Director, International Human Rights Clinic

Fearless. Brilliant. Resilient. As both an advocate and a jurist, Ruth Bader Ginsburg showed us how to use the law, creatively and strategically, to promote justice. Her legacy, of course, is as a champion for the equality of all people and a hero in the struggle for women’s rights.

Her example has always been an inspiration. As law students, my peers and I wanted to be her, or at least be like her. She was a visionary litigator, a tenacious questioner at oral argument, and a witty storyteller. She personified determination and demonstrated how to fight with grace and an apparently tireless energy. Her intellect, strength, and confidence helped us believe in ourselves, our voices, and our contributions.

But more broadly, her legacy implores us to understand that the role of the Supreme Court — and of the legal system itself — is not to engage in a series of debates about abstract or purely intellectual legal propositions. The law is about people, their lives, and their aspirations. Attorneys who use the law to promote social justice must, like Ruth Bader Ginsburg, be mindful of the fundamentally human aspect of our work.

Justice Ginsburg always recognized those who had paved the way for her, even as she broke new ground for us. Although her accomplishments are singular, her legacy teaches us that upholding justice requires a collective effort. Her life’s work is a reminder of the law’s capacity to transform systems and cultures, and to shift power. So, as we mourn this crushing loss, we must continue her fight for equal rights and sustain her commitment to the rule of law.

John F. Manning

Morgan and Helen Chu Dean and Professor of Law, Harvard Law School

Justice Ginsburg personified the best of what it meant to be a judge. She brought a deep intellectual and personal integrity to everything she did. Her powerful and unyielding commitment to the rule of law and to equal justice under law place her among the great Justices in the annals of the court. She was also one of the most impactful lawyers of the 20th century, whose historic work advocating against gender discrimination and for equal rights for all opened doors for countless people and transformed our society. She was an inspiring and courageous human being. We have lost a giant.

Vicki C. Jackson

Laurence H. Tribe Professor of Constitutional Law, Harvard Law School

Justice Ginsburg’s impact on the law is enormous. The gender equality cases she litigated and won, and the gender equality cases she helped decide in the Supreme Court, including VMI, will continue to shape the law for generations to come. Her commitment to “equal justice under law” was not limited to issues of women’s equality. The opinions she wrote in cases involving efforts to overcome America’s history of racial injustice (for example, in affirmative action in public universities or through the Voting Rights Act), and the opinions she joined in cases extending equality norms to LGBTQ persons, bespoke the breadth and depth of her commitment.

Justice Ginsburg loved the law; she believed in the importance of legal procedures; she had a prodigious memory and broad knowledge, which she continued to refresh through reading and research; and she carefully scrutinized laws that she thought were based on unsupported suppositions or stereotypes. She applied her extraordinary analytical mind not only to large, general issues, but also to protect individuals from unfair application of procedural rules.

Her openness about her own life has allowed others to envision paths that combine rewarding work with loving family life and friendships. As she showed, tradition need not determine family roles; tasks can be allocated based on interest or ability (it was Marty Ginsburg who cooked); and even the most demanding workplaces can accommodate parents with young children.

Justice Ginsburg had a rare combination of brilliance, wisdom, awareness of how law affects actual people, and ability to make lasting human connections — with her clients, her colleagues, her staff and others. Her connections to the lived lives of people is reflected in her judicial decisions; for example, her dissent in Lily Ledbetter’s case described workplace “realities” in which gendered compensation disparities “are often hidden from sight.”

Our world was greatly enhanced by her life. And our world is greatly diminished by her passing. She will be much missed and long remembered.

Daphna Renan

Professor of Law, Harvard Law School

RBG was tenacious, unflappable, and deeply wise. She was a visionary in the fight for women’s equality, and she was a fighter until the end. She was as careful with her drafting as she was brave in her argument and powerful in her reasoning. She was grace and grit combined, and she never lost sight of the impact law can have on people’s lives.