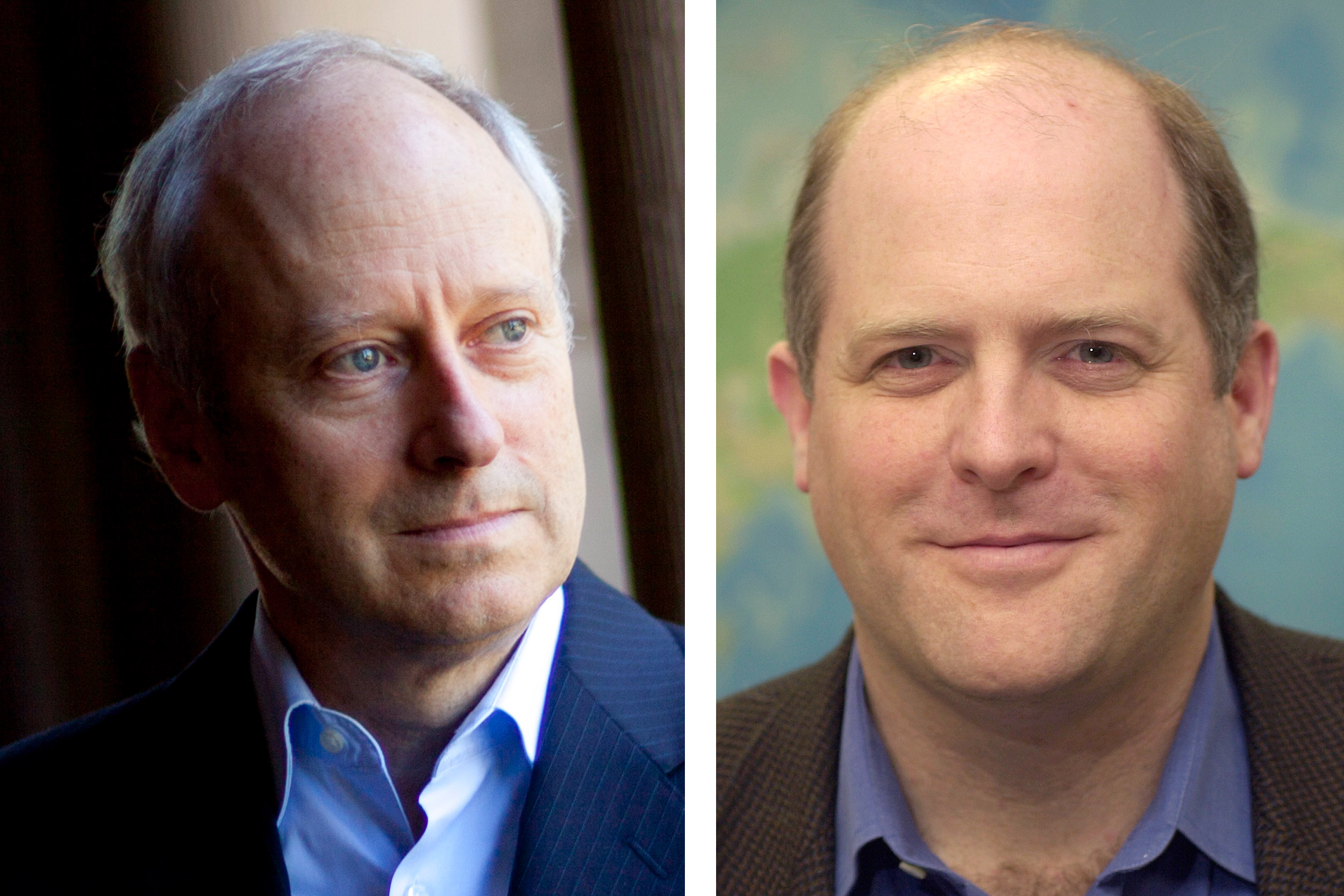

Michael Sandel (left) and Daniel Schrag will teach two University-wide courses using their “One Harvard, One Online Classroom” model.

File photos by Stephanie Mitchell and Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographers

Two online classes aim to bridge all Harvard students, Schools

Sandel on ethics in era of pandemic and racial reckoning, and Schrag on climate change

Two prominent professors are inviting all Harvard degree students to join in two University-wide courses this fall designed to spark conversation and mutual learning across the campuses. Michael Sandel, Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Government, will offer “Justice: Ethics in an Age of Pandemic and Racial Reckoning,” and Daniel Schrag, Sturgis Hooper Professor of Geology and Professor of Environmental Science and Engineering, will teach “Confronting Climate Change: A Foundation in Science, Technology, and Policy.” Every Harvard undergraduate, graduate, and professional school student can enroll in these online courses. The Gazette spoke with Sandel and Schrag to learn about their “One Harvard, One Online Classroom” offerings and how they hope to take advantage of a virtual setting to bring together people who otherwise might not have the chance to learn from each other.

Q&A

Michael Sandel and Daniel Schrag

GAZETTE: How did you both begin to put together courses for this spring that are available to students across the Schools? And how did the University’s shift to virtual learning affect your preparation?

SCHRAG: For me, Michael’s course with Doug Melton on “Tech Ethics,” which debuted last fall, provided the proof that this kind of University-wide course could be successful. This spring, I went for a long walk with Vice Provost for Advances in Learning Bharat Anand, and using Michael and Doug’s course as an example, he said we really should have a similar University-wide course model on climate change as well. And the idea just seemed so obviously a good one. For more than a decade now, I’ve also been talking about how climate change is something that touches every School at Harvard, and requires input from every corner of the University.

Last fall, Michael successfully pulled off his course in person at Klarman Hall at the Business School, and he and Doug did so without a platform such as Zoom, which is extraordinary. Being thrust into remote learning this past March taught all of us that there are some opportunities and advantages of Zoom over conventional teaching: frankly, getting people from the Medical School, and the School of Public Health, and the Business School, and the Divinity School, and the College, and the Design School, and the School of Education all together at the same time, every week.

SANDEL: Climate change is a course that is ideally suited to being a University course; it will be exciting to bring students from across the University into a common conversation from their various disciplinary perspectives about climate change. I’m delighted to be in partnership with Dan in this “One Harvard, One Online Classroom” experiment this coming semester.

When Bharat, Doug, and I discussed our course on tech ethics prior to last fall, we quickly realized that it would lend itself to a University-wide discussion, because it draws on elements of ethics in the humanities, but also in the sciences, medicine, law, public policy, public health, education, and even spiritual matters.

We decided to hold the course in Klarman Hall at HBS, which is a new, stunning, high-tech version of Sanders Theater. We didn’t know whether students from the College would cross the river to attend. But they did. We had about 720 students in total; 600 from Harvard College, and another 120 from the various professional Schools. We did realize, though, that it was harder for students from the Schools on the Longwood campus to attend. I hope the new virtual model will make it easier for them to join us.

GAZETTE: What are your expectations for your courses this semester?

SCHRAG: We’ll have to see how this semester goes and how effective the Zoom platform is for running these courses. I think of my wife, who’s a physician, and since March has been seeing many patients by video. It will be interesting to see if telemedicine becomes a kind of standard for our health care because, boy, it’s a lot easier than going in and waiting in line and parking and all the rest of it to go see your doctor for 20 minutes. I wonder if the same is true for us. I don’t think we’ll go to teaching by Zoom permanently; I think that would be a tragedy because there’s so much advantage to seeing people in person, but I do wonder if selective use of this technology going forward will allow us to teach these kinds of courses more permanently, and if it will have a lasting, positive effect on our work.

SANDEL: I think these are great questions. Dan, you highlight the hopeful side of what has become for us a necessity, this experiment in remote teaching. It will be interesting to see what we learn from it and what educational advantages may come with it.

This semester I’m teaching “Justice: Ethics in an Age of Pandemic and Racial Reckoning.” I’m quite optimistic that the Zoom platform will enable robust, engaged discussion. The questions we explore in “Justice” are our questions about values, including disagreements about values. One of the aims of the course is to invite students to reflect critically on their own moral and political convictions — to reason and argue effectively, to persuade, and be persuaded by, those with whom they disagree. These are the kinds of discussions we’ve traditionally had with students present to one another, in Sanders Theater or Klarman Hall. The challenge will be to see whether this vigorous dialogue, which is a central dimension of the course, can succeed online. I believe it can. There may even be some unexpected advantages.

More like this

SCHRAG: Michael, I’ve watched some of your “Justice” course when it was conducted in person in Sanders Theater, and I must say, I’m absolutely in awe of the way you engage students in the most respectful way, through these debates. I know you must have strong feelings one way or another sometimes yourself, but you treat students respectfully and engage them, challenge them in a very open, encouraging way. My plan for this semester is to break my class up into smaller discussion groups, giving many more people a chance to speak because they will be in groups of six to eight students. The downside of that is I won’t be there as a moderator. And I’m curious about how you’re thinking about that.

SANDEL: I’m still puzzling my way through this. Thank you for the generous question; I consider that we are engaged in this experiment together, notwithstanding the different subject matters of our courses.

I’m trying to strike that balance by combining discussion with the entire class with small breakout group discussions, moving back and forth between the large setting and the small. Some students are comfortable contributing to a large group discussion, while others find it easier to speak up in smaller settings. Reconvening the full class after a breakout session may enable some students who contributed to the small group discussion to feel empowered to speak before the larger group of their classmates. That’s one format we’ll use. On other days, we’re going to use prepared video excerpts of lectures about some of the philosophers, such as Aristotle, Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill, for example, and then have small group discussions led by teaching fellows.

How similar or how different is that from the kind of breakout sessions that that you are planning?

SCHRAG: There’s a huge amount of similarity, I think, in general approach. I’ve prepared the core science and technology content for students to access through about 60 eight- to 10-minute videos, which I liken to mini science documentaries more than lectures. They delve into the basic physics of climate change. How does sea level rise work? What were climates like in the Pleistocene epoch, or the Eocene epoch, 40 million years ago? And how does that relate to global warming today? How are storms being affected by climate change? There’s a lot of information transfer, a little bit like your discussion of the philosophers, through these videos.

Students will watch three or four of these videos each week, but these videos will not be the main focus for the small group conversations. My plan is to spend maybe the first 10 minutes reviewing the major take-home messages from those videos, you know, the absolute essential points that I want everybody to understand. But then I want to transition the class and bring in a voice from the outside. So, for example, yesterday, I recorded our colleague Naomi Oreskes from History of Science talking about climate skeptics. She’s written three books on the subject.

So, the first class, we’re going to listen to Naomi and talk about climate skeptics in a conversation with me, on Zoom, for 10 minutes. We will then go into breakout groups to digest some of the questions that are raised, and then come back to the main group, in a way that is very much similar to what you’re doing. And then use the sections taught by teaching fellows to allow the students to get into the nitty-gritty detail of what was in those video documentaries.

GAZETTE: There’s been a lot of conversation in the field of higher education about how to balance the need for asynchronous content, especially for students who may be living in a time zone far away from their college or university, with synchronous content that brings people together in conversation. It sounds as if you’ve thought of how to provide a balance of both.

SANDEL: I’ve been wrestling with the question of whether to post a full video library right from the start of the semester, and say, if you want to binge watch, racing ahead, you can. The drawback of the binge-watching approach is that it makes it harder for students to absorb and discuss this material with me, with their teaching fellows, and with their classmates.

SCHRAG: I have another question for Michael. One of the key parts of my class is a project, which this year, because of the virtual format, will be done in small groups. This project is a very practical one: It’s designing a zero-carbon economy, and it forces students to think about this problem in a way that goes way beyond just a lecture, and into experiential learning. I’m curious how that’s going to work out in this virtual semester, but I’m hoping it’s going to be effective. Is there anything comparable in your class?

SANDEL: I’ve also been trying to think about this; how to encourage students to work together, while still giving students the option of doing and submitting their own work for evaluation. We’re offering two options. One track is the traditional paper option: three short papers on a range of topics about ethical questions. This is designed to equip students to write a clear, analytic, persuasive argument about an ethical question, drawing where relevant on the philosophers, but making an argument in their own voice. The other track is one traditional paper, and a project that culminates in a podcast, or a video, that develops a persuasive argument about an ethical question.

The team of former teaching fellows who helped me develop this course over the summer made the point that if we’re teaching students to reason in public about hard ethical questions, we should give them the option of creating something that could actually be posted online as a contribution to public debate. They encouraged me to add the podcast option. Like a traditional paper, it would analyze the ethical dimensions of a contemporary issue. But it would be in a format that could be made available online, if the student wanted to. We are also giving students the option to work in pairs, especially if they want to do the podcast as a kind of dialogue or debate, with arguments and counter arguments.

GAZETTE: The courses both sound fascinating. Best of luck in this new virtual learning model. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

SCHRAG: I regret to say that in the 23 years that I’ve been at Harvard, I have never sat through a College course in its entirety. And, honestly, watching parts of Michael’s course that are available online, I wish that I had the discipline to make the time to take it in, in its entirety, because it makes you appreciate the incredible wealth of knowledge that exists around this University. I’m hopeful that our “One Harvard, One Online Classroom” offerings will bring together some of the brilliant, diverse minds that make Harvard what it is, and might never meet in our normal mode of teaching.

SANDEL: I feel the same way, and would love to sign up for “Climate Change.” It’s going to be a wonderful course.

Students who would like more information on either course can find it here, on Canvas:

GENED 1171 Justice: Ethics in an Age of Pandemic and Racial Reckoning;

GENED 1094 Confronting Climate Change: A Foundation in Science, Technology and Policy.