In a warming world, New England’s trees are storing more carbon

Unprecedented 25-year study traced forest carbon through air, trees, soil, and water

The world’s longest-running eddy-flux tower, the Harvard Forest Environmental Measurements Station, measures atmospheric carbon dioxide entering and leaving an oak-maple forest.

Photo by David Foster

Climate change has increased the productivity of forests, according to a new study that synthesizes hundreds of thousands of carbon observations collected over the last quarter century at the Harvard Forest Long-Term Ecological Research site, one of the most intensively studied forests in the world.

The study, published today in Ecological Monographs, reveals that the rate at which carbon is captured from the atmosphere at Harvard Forest nearly doubled between 1992 and 2015. The scientists attribute much of the increase in storage capacity to the growth of 100-year-old oak trees, still vigorously rebounding from colonial-era land clearing, intensive timber harvest, and the 1938 Hurricane — and bolstered more recently by increasing temperatures and a longer growing season due to climate change. Trees have also been growing faster due to regional increases in precipitation and atmospheric carbon dioxide, while decreases in atmospheric pollutants such as ozone, sulfur, and nitrogen have reduced forest stress.

“It is remarkable that changes in climate and atmospheric chemistry within our own lifetimes have accelerated the rate at which forest are capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere,” says Adrien Finzi, professor of biology at Boston University and a co-lead author of the study.

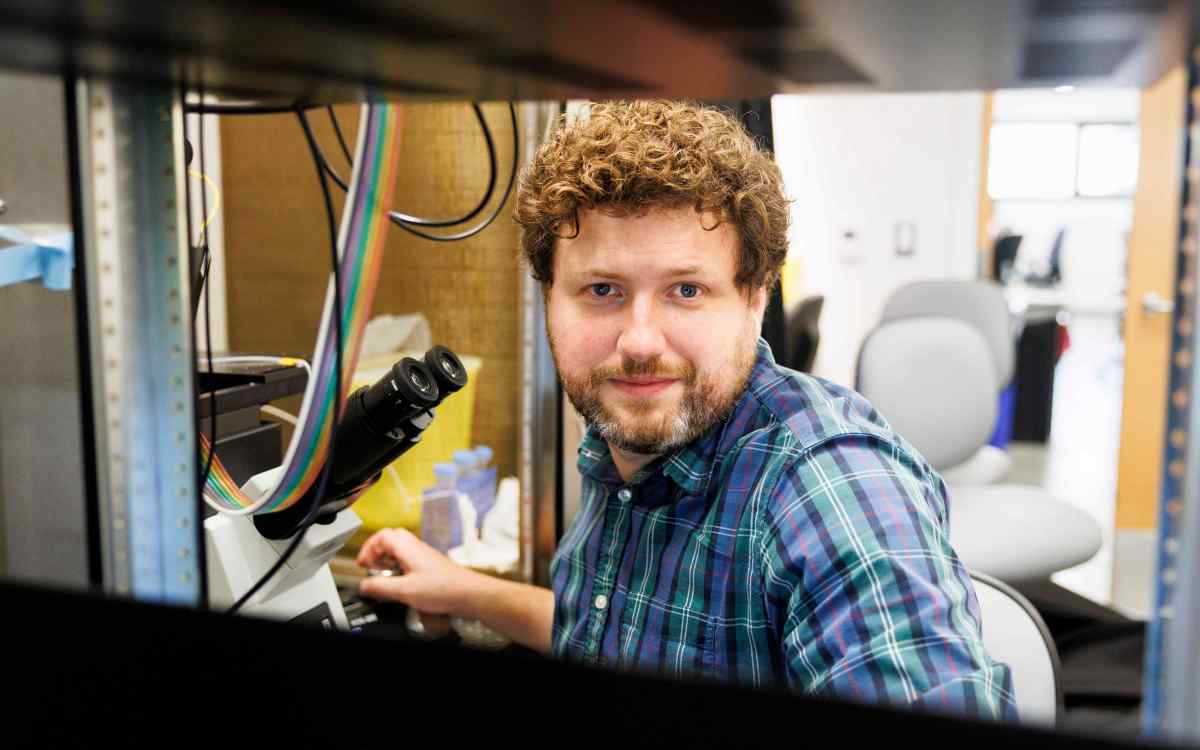

An automated soil respiration chamber measures carbon dioxide emitted by the soil as plant roots and microscopic organisms use energy. Postdoctoral fellow Tim Rademacher and student researcher Kyle Wyche measure the respiration of an oak tree at Harvard Forest.

Photos by Marc-Andre Giasson and Sara Plisinski

The volume of data brought together for the analysis — by two dozen scientists from 11 institutions — is unprecedented, as is the consistency of the results. Carbon measurements taken in air, soil, water, and trees are notoriously difficult to reconcile, in part because of the different timescales on which the processes operate. But when viewed together, a nearly complete carbon budget — one of the holy grails of ecology — emerges, documenting the flow of carbon through the forest in a complex, multi-decadal circuit.

“Our data show that the growth of trees is the engine that drives carbon storage in this forest ecosystem,” says Audrey Barker Plotkin, senior ecologist at Harvard Forest and a co-lead author of the study. “Soils contain a lot of the forest’s carbon — about half of the total — but that storage hasn’t changed much in the past quarter-century.”

The trees show no signs of slowing their growth, even as they come into their second century of life. But the scientists note that what we see today may not be the forest’s future. “It’s entirely possible that other forest development processes like tree age may dampen or reverse the pattern we’ve observed,” says Finzi.

The study revealed other seeds of vulnerability resulting from climate change and human activity, such as the spread of invasive insects.

More like this

At Harvard Forest, hemlock-dominated forests were accumulating carbon at similar rates to hardwood forests until the arrival of the hemlock woolly adelgid, an invasive insect, in the early 2000s. In 2014, as more trees began to die, the hemlock forest switched from a carbon “sink,” which stores carbon, to a carbon “source,” which releases more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere than it captures.

The research team also points to extreme storms, suburbanization, and the recent relaxation of federal air and water quality standards as pressures that could reverse the gains forests have made.

“Witnessing in real time the rapid decline of our beloved hemlock forest makes the threat of future losses very real,” says Barker Plotkin. “It’s important to recognize the vital service forests are providing now, and to safeguard those into the future.”