‘What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?’

Community reading to explore the resonance of Frederick Douglass’ famous speech

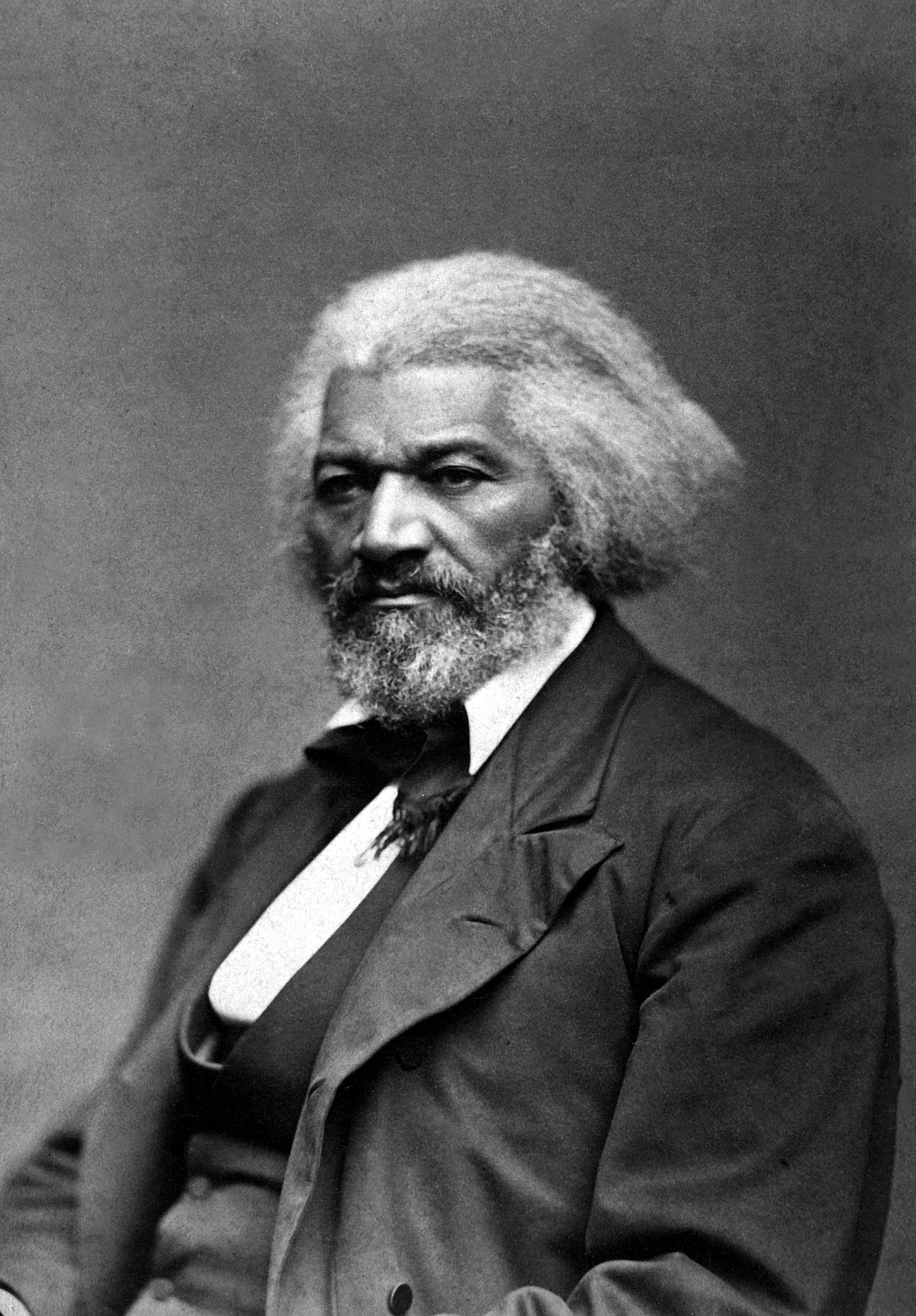

Frederick Douglass, circa 1879.

Photo courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration

Frederick Douglass delivered his famous speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” in 1852, drawing parallels between the Revolutionary War and the fight to abolish slavery. He implored the Rochester, N.Y., audience to think about the ongoing oppression of Black Americans during a holiday celebrating freedom. “Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting. America is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself to be false to the future,” Douglass said. More than 150 years later, Keidrick Roy, a doctoral student in American Studies at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and a U.S. Air Force veteran, will host a virtual community reading and discussion of the storied speech at the Somerville Museum on Thursday as part of the annual state-wide MassHumanities program “Reading Frederick Douglass Together.”

Q&A

Keidrick Roy

GAZETTE: What is the historical setting for this speech, and why did Douglass focus on the Fourth of July?

ROY: Douglass wrote the speech in the wake of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which effectively extended the reach of slave power in the South throughout the rest of the country. [Under the Act] it became illegal not to arrest and return runaway slaves. The Act also denied suspected slaves trial by jury or even the ability to testify on their own behalf in court. And it also imposed severe penalties on anyone who helped enslaved people to escape. In short, it gave the federal government an active role in maintaining the South’s system of slavery.

One of the parts of the speech that resonates with me the most is when Douglass says: “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim.” [Throughout the speech] Douglass looks at the contradictions between the reality of slavery and the lofty claims of a just society outlined in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

“We need individual events like reading Douglass, but we also need to be thinking about ways to extend this conversation over the long term.”

GAZETTE: This is your second year as host of “Reading Frederick Douglass Together” in Somerville. What will this year’s event be like?

ROY: The event that we’re doing in Somerville puts pressure on whitewashed conceptions of the Fourth of July, as many people to this day still view it as a celebration of American food, fireworks, and freedom. This year is pretty challenging in the wake of COVID-19, and the event is going to be held online instead of before a live audience like we did last year. Alison Drasner, the project coordinator for the Somerville Museum, teamed up with Dave Ortega at the Somerville Media Center to prerecord voices of 50 Somerville residents, including my 7-year-old daughter, Charlotte, to read sections of the speech. As the project scholar, my role is to advise the process as it rolls out, to give a talk that provides contemporary and historical context and to facilitate the community discussion around the speech against the backdrop of other relevant issues.

I am also hosting a summer reading and discussion series called “Race, Fragility, and Anti-Racism” through the Somerville Museum and the City on a Hill network of local churches. We’re not only going to be reading books like “White Fragility,” and “Divided by Faith,” but we’re also going to read and watch a number of speeches by Martin Luther King Jr., and documentaries like “13th” and “King in the Wilderness,” as we try to get at the root of racial division so we can come together to remove it. We need individual events like reading Douglass, but we also need to be thinking about ways to extend this conversation over the long term.

GAZETTE: Why is it important to do this kind of community-building work at a local level?

ROY: The better we get to know the people that we live with, that we work around, that we see at the coffee shop, and the more we talk about these important racial issues with one another, the easier it will be to heal our divided communities.

Keidrick Roy, the host of the virtual reading event.

Photo by Bimal Nepal

One of the biggest challenges we face in our present moment is building sustainable movements that fundamentally change people’s minds about race and racism. If you’re not a person of color, it’s one thing to go to a couple of events or protests, or to read a few articles and move on. But it’s quite another to change the way you see yourself and to grow into a person deeply committed to long-term interracial coalition building. So it’s important that our city and our society are outraged by the recent murders of unarmed black people. But we also need to invest as a city and as a society into reading and learning more about the present realities of oppressed peoples. At the same time, we need to be studying the history of slavery and racism in this country so we can build policies, practices, and procedures that address the present problems with those historical inequities in mind.

GAZETTE: What is something you have discovered about Douglass while researching this speech and his work more broadly that people might be surprised to learn?

ROY: One of the things that Douglass’ writings shows us is that he believed in amplifying a variety of voices. He took action to raise the voices of others and to aid their work on the national stage, especially that of two Black women in the last half of the 19th century. He wrote a glowing letter of encouragement to Harriet Tubman, which served as the preface to Sarah Bradford’s 1869 biography about Tubman’s life. He also wrote a letter to Ida B. Wells, which was incorporated into the preface of her 1892 pamphlet “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.”

Another remarkable thing about Douglass is that he was an early champion of voting rights for women. In an 1868 speech, he said, “No man should be excluded from the government on the basis of his color, no woman on account of her sex. There should be no shoulder that does not bear the burden of the government.” He had a prophetic vision for the future that he was always trying to work toward.

Interview was lightly edited for clarity and length.