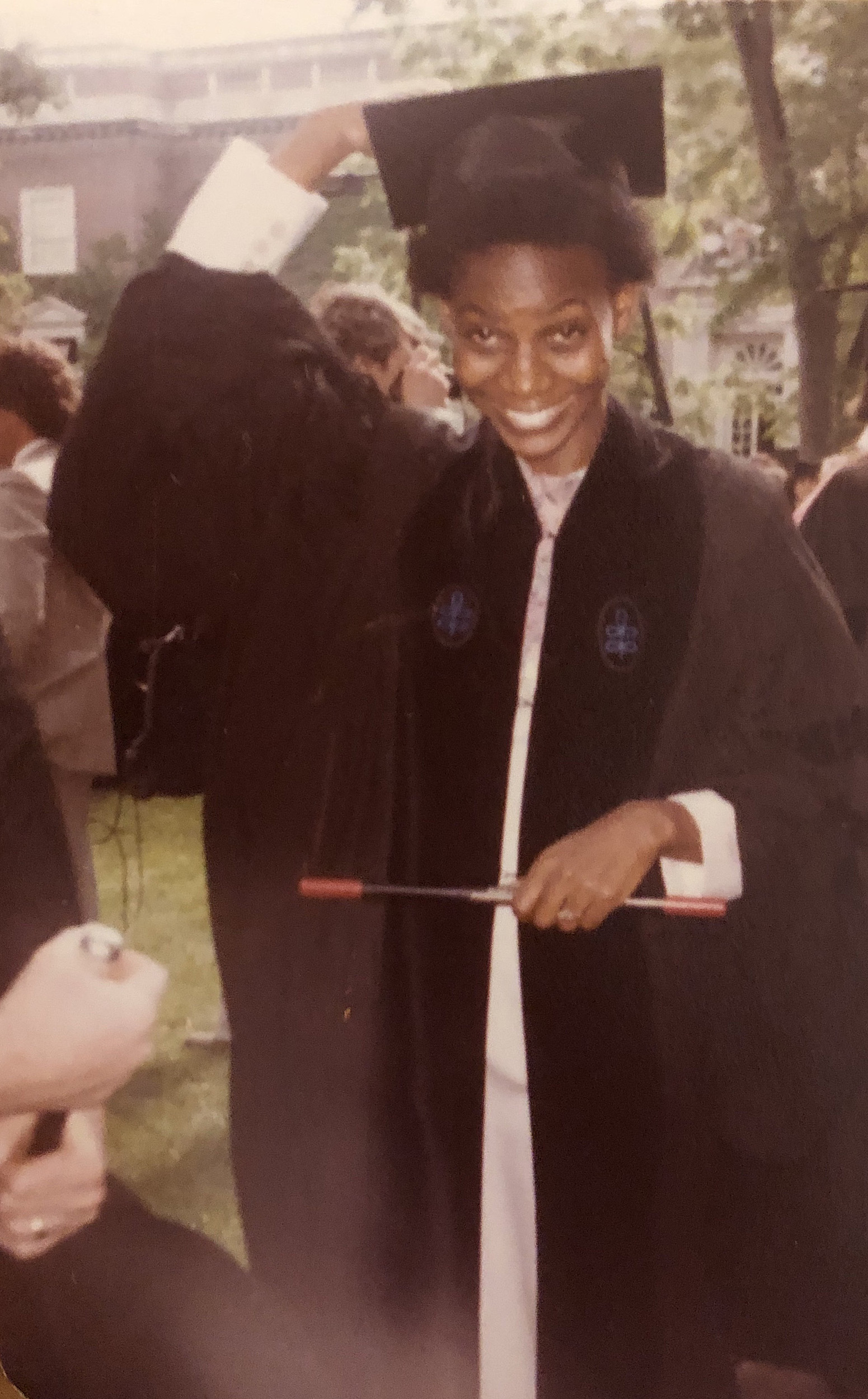

Deborah Washington Brown at her graduation in 1981.

Photos courtesy of the Brown family

Breaking barriers

Deborah Washington Brown, the first Black woman to earn an applied math Ph.D. at Harvard, passed away June 5

Humble and soft-spoken, Deborah Washington Brown would never have described herself as a trailblazer.

But as the first Black woman to graduate from the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in 1981 with a Ph.D. in applied mathematics, she shattered the racial and gender barriers that still plague technology fields today.

Brown was the first Black computer scientist to earn a Ph.D. in the applied mathematics program at Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences , and also one of the first Black, female computer scientists to graduate from a U.S. doctoral program.

Though she passed away on June 5 after a long battle with cancer, her achievements and legacy remain as an inspiration for those who have followed in her footsteps.

Brown was born in Washington, D.C., on June 3, 1952. The youngest of four children, Brown’s mother worked as a hairdresser and her father was a taxi cab driver. Her parents, who had both grown up in the segregated south, worked hard to provide a better life for their children and encouraged Brown and her siblings to explore their passions.

From an early age, Brown was passionate about math and music.

“She was the family brainiac,” her daughter, Laurel Brown, recalls. “One time, when she was a young girl, she and her siblings went with their uncle on a cross-country road trip. Their uncle was a bit of a spendthrift, so he designated my mother to be his human calculator. She was in charge of calculating the gas mileage and making sure he wasn’t spending too much money on the road trip. She always had this propensity for math and numbers.”

Deborah Washington Brown playing the piano, one of her lifelong passions outside of academia.

She may have had a knack for math, but her true love was the piano. Brown started playing classical music at age 6 and quickly blossomed into an accomplished pianist, winning numerous piano competitions throughout the Capital Area.

After graduating from the National Cathedral High School in Washington, D.C., she was admitted into the New England Conservatory of Music to study classical piano. Brown traveled to New England, ready to pursue her passion at the storied institution, but her dreams were soon derailed.

“She never talked much about that time. I learned later that she overheard one of her teachers saying that they couldn’t expect much from her, especially given the fact that her father was a taxicab driver,” Laurel said. “So she dropped out. Her passion was music, and though her hopes had been dashed, since she was so good at math she enrolled at Lowell Tech instead.”

Brown graduated with honors, earning a bachelor’s degree in math from Lowell Tech in 1975, and a prestigious IBM Fellowship to help pay for her graduate studies. But Lowell Tech (now part of the University of Massachusetts Lowell) was not a traditional feeder for Harvard graduate programs.

Laurel still isn’t sure what motivated her mother to apply in 1974.

Harry R. Lewis, Gordon McKay Professor of Computer Science, who was then a first-year faculty member at SEAS, served on the Ph.D. admissions committee and still recalls Brown’s application (and her impeccable handwriting). Students admitted into the applied math/computer science Ph.D. program typically hailed from schools like MIT, Princeton, Yale, Cornell, Berkeley, and a few reliably strong universities in China and Greece.

“So when I glanced at an application from Lowell, I nearly set it aside without a second look. Then I saw the name, Deborah Blanche Washington, and considered it more closely,” Lewis recalled.

“I learned later that [my mother] overheard one of her teachers saying that they couldn’t expect much from her, especially given the fact that her father was a taxicab driver.”

Laurel, Deborah Washington Brown’s daughter

Lewis was impressed by Brown’s perfect transcript and the over-the-top letters of support submitted with her application. So he took the then-unusual step of inviting her to campus for an interview.

“My recollection is that we were both scared since the situation was new to both of us, but that actually made the conversation quite pleasant,” he said. “She was admitted and came, and I advised her for a time.”

Brown served as a teaching fellow for Lewis’ course, “Automatic Computing” (Nat Sci 110). At SEAS, her research focused on practical quandaries in computer programming. She eventually switched advisors and, in the lab of computer scientist Thomas Cheatham, completed her dissertation, titled, “The solution of difference equations describing array manipulation in program loops.”

In addition to achieving academic success, she also earned the respect of her peers; Brown was elected to be a Commencement marshal in 1981.

After earning her Ph.D., she joined Connecticut defense contractor Norden Systems, where she worked on missile defense technology. The bulk of her professional work centered on artificial intelligence and speech recognition technology. She spent more than a decade at Bell Labs and also worked for AT&T, Verizon Wireless, and Speech-Soft Solutions as a speech scientist and speech technology specialist.

During her career, she was awarded at least 10 patents, either individually or with collaborators. In 2013, she received a patent as the sole inventor of an AI-driven system to automatically categorize a speech transcription based on the context of its subject matter. Brown’s most recent patent was awarded in 2019.

Though she spent her days tackling thorny computer science problems, Brown, who also taught math for a time at several colleges in Georgia, never lost sight of her passion for music. She continued to study — and teach — piano, winning numerous awards and performing all around the world, from Carnegie Hall to Italy and Germany. She also earned a level 10 certification from the Royal Conservatory of Music.

But her first priority, even as she achieved success as a computer scientist and musician, was always being a good mother to her two daughters, Laurel recalls.

“She always encouraged me. I also have a propensity for math, and, because of my mother, I didn’t even realize until I was in college that there was any type of gender or race gap in STEM,” Laurel said. “My mother was good at math and computer science. So I never had to second guess myself or my abilities because of the example she set for me.”

And it was her mother’s support and encouragement that ultimately inspired Laurel to apply to Harvard Law School, from which she graduated in 2005.

“I was born in 1980, so I was at her Harvard graduation, and 24 years later, she was at mine,” Laurel said. “I always felt so close to her because we shared that Harvard connection.”

For Laurel, who works in economic development in New York City, the lessons she learned from her mother about perseverance and humility continue to serve as an inspiration.

“She was so humble, and that’s what made her a powerhouse. That’s why people respected her so much,” Laurel said. “She was just this really soft-spoken, quiet lady who, by virtue of just living her life, made this impact, but wasn’t necessarily out to do so. She just did it.”