What we know and don’t know about pot

Unsplash

Medical School’s Kevin Hill talks about fearmongering and rosy myths, safe use and addiction

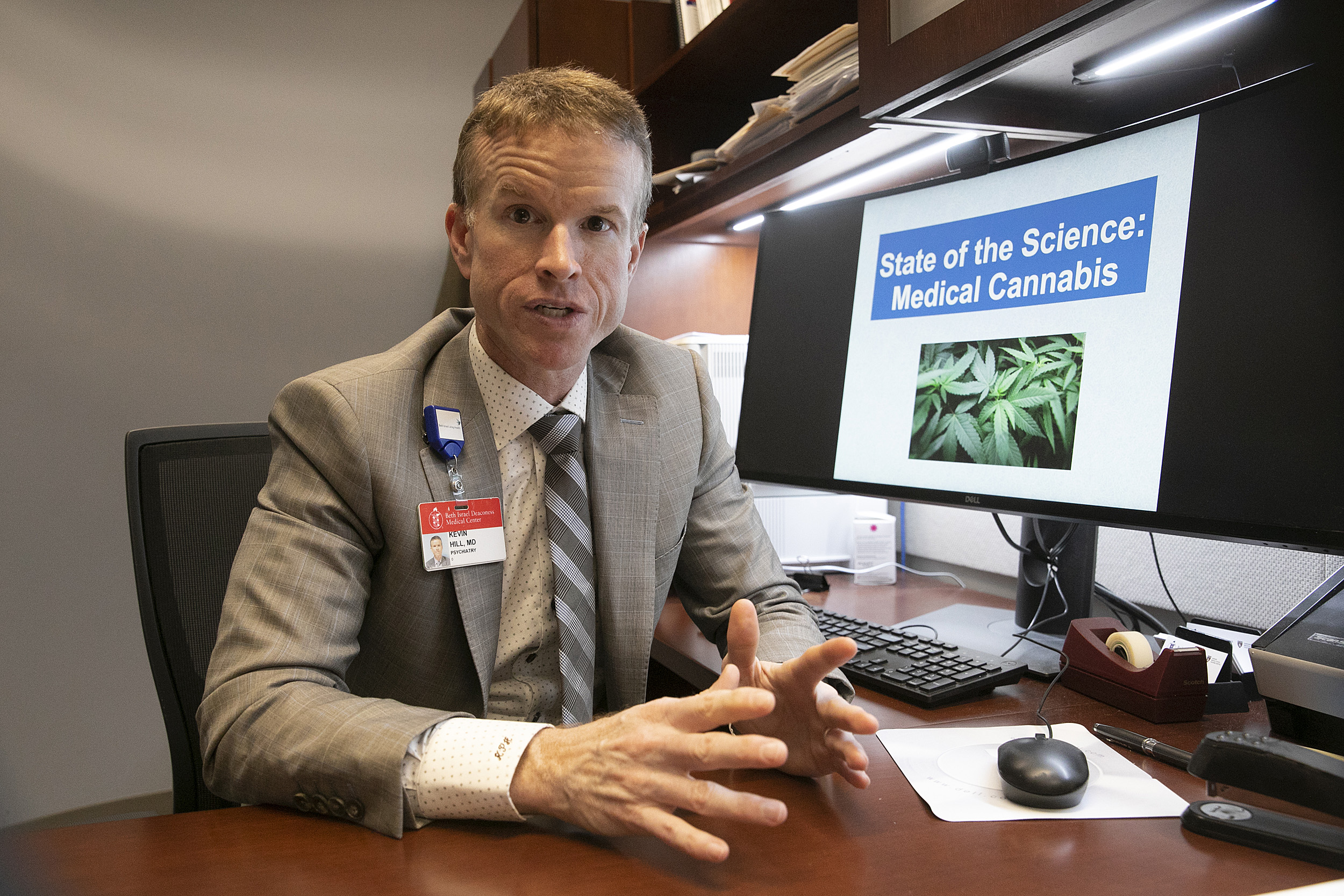

The legalization of marijuana has spread around the country in recent years. Currently 33 states allow it for medical use and 11 for recreational. Yet scientists and researchers say a paradox about it endures: There has been broad public experience with pot, but the medical community still doesn’t know enough about the health effects — and what it does know is often obscured by enduring myths. Kevin Hill, associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of the Division of Addiction Psychiatry at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, has conducted marijuana-related research and is the author of the 2015 book “Marijuana: The Unbiased Truth about the World’s Most Popular Weed.” He is also co-chair of the National Football League’s Pain Management Committee, which is evaluating a possible role for cannabinoids in treatment. The Gazette spoke with Hill about where we are now in understanding the drug’s pluses and minuses.

Q&A

Kevin Hill

GAZETTE: Marijuana legalization has swept the country over the last couple of years. What do we know now about its health effects that we didn’t know before?

HILL: We know a lot more about both the benefits and the risks of cannabis use, although I would say that the rate and scale of research has not kept pace with the interest. There is a growing body of literature on the therapeutic use of cannabis and, similarly, we’re learning bits and pieces about the problems associated with cannabis use. But our increased knowledge pales in comparison to the intense public interest, so one of the issues we often encounter is a growing divide between what the science says and what public perception is.

“There are a lot of things we don’t know, and a lot of answers we wouldn’t have expected” says Kevin Hill, who has conducted marijuana-related research and is the author of “Marijuana: The Unbiased Truth about the World’s Most Popular Weed.”

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

GAZETTE: Is it that there are myths that haven’t been dispelled yet, either by widespread experience or by scientific findings?

HILL: The myths have been disproven. Unfortunately, the loudest voices in the cannabis debate often are people who have political or financial skin in the game, and the two sides are entrenched. Pro-cannabis people will say that cannabis is the greatest medication ever, and harmless. Others — often in the same field that I’m in, people who treat patients, people who do research with cannabis — will at times misrepresent the facts as well. They will go into a room of 100 or 200 high schoolers and relay the message that cannabis is as dangerous as fentanyl. That’s not true either. These camps seem to feel that even a single shred of evidence that runs counter to their narrative hurts them. So at the end of the day, a lot of what people hear about cannabis is either incomplete or flat-out wrong because both sides are promoting polar opposite views of cannabis.

GAZETTE: What is an example of these myths?

HILL: I think the greatest example is when you talk about the addictive nature of cannabis. You can become addicted to cannabis, though most people don’t. Yet invariably, when people hear about what I do, they say, “Oh, you’re an addiction psychiatrist? Well, cannabis is not physically addictive; it’s psychological.” So there are fallacies about cannabis. And they continue because people are invested in trying to get people to vote one way or another on issues like medical cannabis or legalization of recreational cannabis. That is a major problem. Every single day we have patients come in who are interested in using cannabis as a medication or they’re using it recreationally or are interested in cannabidiol, and they have beliefs about cannabis that they’ve held for years that aren’t true. And that becomes a major barrier. It’s hard to dispel those beliefs in the office.

GAZETTE: What is cannabis addiction like?

HILL: It’s less addictive than alcohol, less addictive than opioids, but just because it’s less addictive doesn’t mean that it’s not addictive. There’s a subset of people — whom I treat frequently — who are using cannabis to the detriment of work, school, and relationships. It’s hard for the majority of people — who may use once a month or once every six months, or they tried it in Vegas because it’s legal there — to recognize the reality that there are many people who are using and losing in key areas of their lives. I’ve had patients who have lost multimillion-dollar careers. It’s hard for people to understand that that can happen. I often compare cannabis to alcohol. They’re very similar in that most people who use never need to see somebody like me. But the difference is that we all recognize the dangers of alcohol. If you go into a room of 200 high school kids, they know it’s dangerous and binge drinking among high schoolers is way down. But if you ask that same group about cannabis, you’re going to get all different answers. Data that suggests that although cannabis use among young people is flat — that’s another misrepresentation, that it’s going up — the perception of risk among those young people is going down. So, while everyone’s talking about it, and stores are opening in Brookline, in Leicester, and all over the state, adults and young people are not clear about the risks.

GAZETTE: What about the other side, myths about cannabis’ harms?

HILL: How are things misrepresented by anti-cannabis crusaders? They tend to ignore the idea that dose matters. When we talk about the harms of cannabis, young people using regularly can have cognitive problems, up to an eight-point loss of IQ over time. It can worsen depression. It can worsen anxiety. But all of those consequences depend upon the dose. The data that shows those impacts look at young people who are using pretty much every day. They’re heavy users who usually meet criteria for cannabis-use disorder. So when people who are opposed to cannabis talk about those harms, they don’t mention that they’re talking about heavy users. The 16-year-old kid who uses once or twice a week, I’d still be worried about it, but that use has not been correlated to these harms.

“It’s less addictive than alcohol, less addictive than opioids, but just because it’s less addictive doesn’t mean that it’s not addictive.”

GAZETTE: What constitutes heavy use?

HILL: Cannabis is different than alcohol, because with alcohol, you can use once a week, three times a week, and it can be a problem. You can have eight drinks once a week and get into a whole bunch of trouble. Cannabis is a little different in the sense that the people who run into trouble are using it pretty much every day, multiple times a day for the most part. That’s how this less-harmful, less-addictive substance turns into something that’s very harmful for them.

GAZETTE: Are the characteristics of cannabis addiction common to other types of addiction?

HILL: They are. When someone’s sitting in my office, if you redacted some of the details of their story, it’d be hard to tell who’s got which problem: alcohol versus opioids versus cannabis. The onset — what will bring you into my office — is different. People who are using cannabis are not going to knock off a CVS to fuel their habit. If somebody’s using fentanyl, they may overdose and that could be potentially fatal. That’s not going to happen with cannabis. But when you talk to them, other details are often the same. “My wife said I gotta come talk to you or she’s gonna kick me out.” And that can happen to somebody who’s drinking, that could happen to somebody using opioids. It’s not as dramatic if cannabis is the drug of choice, but once somebody meets the criteria for a cannabis-use disorder or alcohol-use disorder or opioid-use disorder, there are a lot of similarities, more similarities than differences, frankly. One unique thing about cannabis is that on the same day, I may have somebody who is 26, smoking four times a day, graduated from a local elite university, and not making it like they want to be making it. Then, the next hour, I may see a 70-year-old woman who has chronic back issues and tried multiple medications, multiple injections, and wants to use cannabis for her pain. There aren’t a lot of doctors who see both of these patients and that is one of the reasons why people take really strong positions, when in fact many of the answers on cannabis are down the middle. There are a lot of things we don’t know, and a lot of answers we wouldn’t have expected. I’ve done studies myself where I hypothesized one thing, and something else comes out. Are you going to dismiss that or let that new information shape what you think about cannabis? You have to be open-minded in an area that is continuing to evolve. If you aren’t open-minded and willing to have a sensible conversation about cannabis, you won’t be able to reach your patients. A lot of times patients don’t tell their primary care doctor about their cannabis use, their use of CBD, because they think their physician won’t approve of their use. That’s another major problem. If you’re using CBD to treat a given medical condition and your doctor doesn’t know it and you’ve got six other medications, that could be a major issue.

“When we talk about the harms of cannabis, young people using regularly can have cognitive problems, up to an eight-point loss of IQ over time. It can worsen depression. It can worsen anxiety. But all of those consequences depend upon the dose.”

GAZETTE: We’ve talked about negatives. What is the truth of the positive health benefits?

HILL: We’re conditioned as physicians to believe that cannabis is bad for you, but there is data that it can be useful in certain cases. I would prefer that we use FDA-approved medications when possible. They are much safer, and you can be sure of the purity and potency. But there is evidence to support the use of cannabis and cannabinoids for a handful of medical conditions. That is dwarfed by the number of conditions for which people are actually using it, but the evidence of benefit is not zero. To a lot of doctors, it’d be convenient if it was zero so they could tell patients that this whole idea is a sham. Thus, there are physicians who aren’t willing to entertain data demonstrating therapeutic use of cannabis. I think that’s a missed opportunity because if a patient comes in and says, “I want to use cannabis to treat condition x,” cannabis might not be the best treatment for that condition, but just being willing to engage in a conversation about it, you may get them into treatment they might not otherwise get into. If they said, “Look, I want to use cannabis to treat my anxiety,” I’m not going to recommend using whole-plant cannabis to treat anxiety, but maybe they haven’t tried cognitive behavioral therapy. Just by having that conversation, you could do a lot of good.

GAZETTE: Is pain one area that cannabis is proven for?

HILL: In 2015, we had two FDA-approved cannabinoids, dronabinol and nabilone, for nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy, and for appetite stimulation in wasting conditions. Last year they added cannabidiol — only one version is FDA-approved — and it is for a couple of pediatric epilepsy conditions. Beyond the FDA-approved indications, the best evidence is for three things: chronic pain, neuropathic pain — which is a burning sensation in your nerves — and muscle spasticity associated with multiple sclerosis. There are more than six randomized control trials for each of those three conditions. There are problems associated with some of those trials — sample sizes are small and the follow-up periods are not as long as we would like them to be. I wish there was better evidence for chronic pain, but as long as we have a clear conversation about what the risks may be, then to me, there’s enough evidence for those three things to think about cannabis or cannabinoids not as first-line or second-line treatments but as third-line treatments.

GAZETTE: The House Judiciary Committee recently approved a bill removing cannabis as a Schedule 1 controlled substance. There’s a long way to go with that legislation, but would that step make it easier to conduct the studies that will clear some of the confusion?

HILL: Schedule 1 really means two things. Number one, does it have addictive potential? Cannabis does, clearly. But it also means that there is no medical value. I think you’re hard-pressed at this point to say that cannabis and cannabinoids have no medical value. So I don’t think it should be a Schedule 1 substance and changing that really would make it a lot easier to study. Funding is a bigger barrier. I’m sitting in a state right now that is profiting from cannabis. I’ve got a store a mile away from my hospital, and they’re printing money. It’s raining out, snowing, and there are people lined up outside of the store to buy cannabis. There are permanent crowd-control ropes in the parking lot and a police detail. A lot of people are profiting from cannabis while neglecting to contribute to the scientific evidence base. It shouldn’t be that way.

GAZETTE: What is most important for the public to know about this?

HILL: Over 22 million Americans used cannabis last year, and the literature says about 10 percent of those are using medicinally. If that’s true, a lot of those people are just talking to physicians who write certifications all day. That means there isn’t the level of follow-up that should be there; the standard of care is lower than it should be. I think patients who are interested in cannabinoids should be talking to their own doctors about it, because ideally, their physician should be the one helping them think through the risks and benefits.

GAZETTE: With cannabis legalized recreationally, why shouldn’t people interested in it as a medicine just say, “Well, I’ll go buy some”?

HILL: That question opens the door to the poor job we’ve done educating people about cannabis. A lot of people want to try it, but they’re not educated about how it works. They don’t know what the typical dose is or the onset of action with edibles. The number of ED visits has gone up. People may say, “Oh, there is a store on Route 9. I’m going to go. I never tried it before.” And, whether they’re in Las Vegas or Colorado or someplace else, they repeat the same mistakes. They’re not going to have a fatal overdose, but they can get very sick and that should never happen.

GAZETTE: So, if you have a glass of alcohol, you know roughly what the effect might be on your body. But for a particular dose of pot, we have no clue?

HILL: Less of a clue. A typical brownie has 100 milligrams of THC, but a typical serving size is 10 milligrams. I don’t know about you, but when I’m eating a brownie, I eat the whole brownie. So, it’s the idea that if you’re going to use an edible and you’re buying a brownie then you’re going to consume a tenth of it, or if you eat cannabis, it’s going to take longer than if you were to smoke it. Some people will take a bite of an edible and nothing happens, so they take another bite. A half-hour later, they’ve got four or five times the typical dose. So long as you know that, you’re not going to have an issue. But if you’re not aware of that and you have more, if you’ve never used it before, 40 to 50 milligrams of THC is going to knock you for a loop. So if you’re going to use recreationally or medically, you need to be educated about what you’re doing.