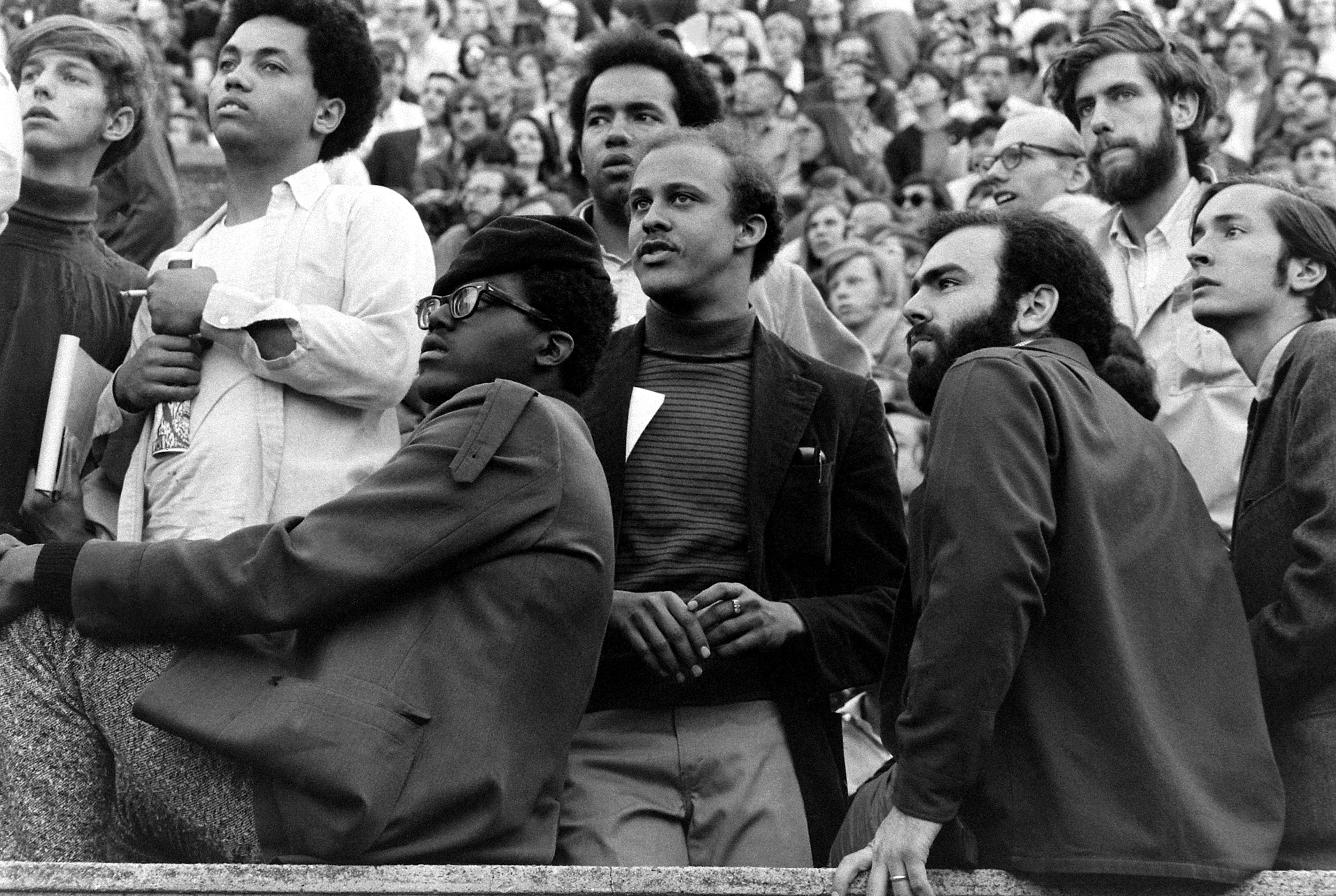

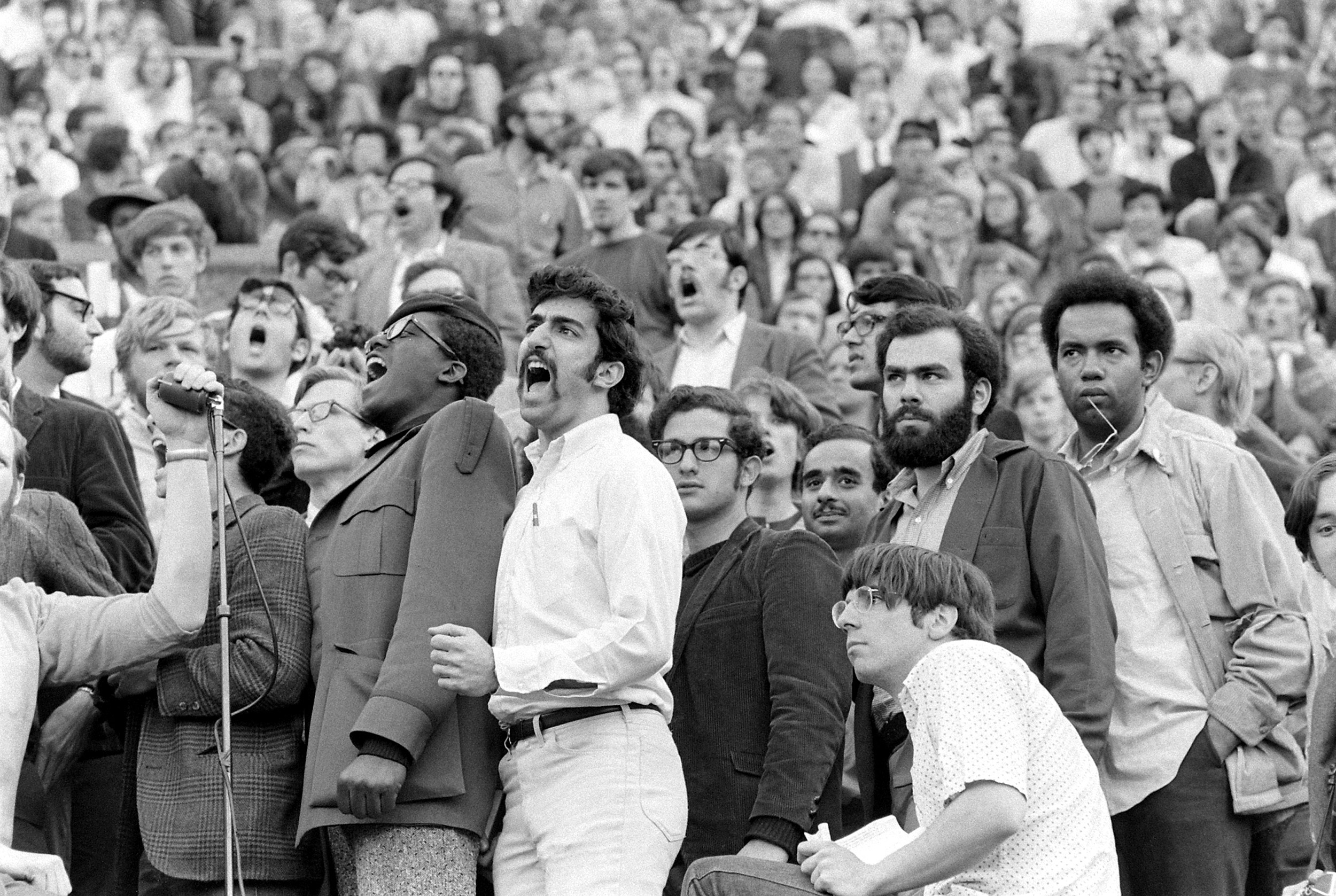

Student activists staged a mass rally that took place at Harvard Stadium in April 1969.

Getty Images/Life Magazine

African and African American Studies at 50

Influential, groundbreaking department marks its founding with a symposium that looks back and into the future

In 1968, a black student group placed an advertisement in the Harvard Crimson calling for the College to give black students, faculty, and scholarship more support and greater representation on campus. Following months of negotiations, amid a general atmosphere of student unrest and demands for change, the campaign eventually led to the creation of the Afro-American Studies Department in 1969.

In the ensuing decades, the interdisciplinary department has changed its name to African and African American Studies (AAAS), established a strong identity on campus, and expanded in size and influence, nationally and internationally, across fields more numerous than its name might suggest.

To mark its 50th anniversary, AAAS will launch a two-day symposium beginning Friday, commemorating its history and celebrating the continuing work of its students and scholars. The events, which include panel discussions, musical performances, gallery displays, and keynote addresses, are free and open to the public.

“In many ways, I wanted to emphasize the things that have changed” in the past decades, said Tommie Shelby, Caldwell Titcomb Professor of African and African American Studies and of Philosophy. Shelby serves as department chair of AAAS and organized the event with input from its faculty, students, and staff. “This department was initially established as one that was focused on North America, and now it is very much part of our mission that, in addition to African American studies, we also try to cover much of the Caribbean, Latin America, and Africa as well. We want to highlight the breadth of what we’re covering and the fact that the department is now so much bigger than it was.”

Department chair of AAAS Tommie Shelby organized the two-day symposium.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

“No one could have imagined that 30 years ago we’d be where we are now,” said Henry Louis Gates Jr., Alphonse Fletcher Jr. University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, who joined the department in 1991 and served as its chair for 15 years. “African and African American Studies is inextricably intertwined with the intellectual life and culture of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences at Harvard.”

Events will include a roundtable discussion with founders, performances by the Kuumba Singers of Harvard College, panels on scholar-activism in the field and the future of graduate studies, and keynote addresses by Columbia University Professor Farah Jasmine Griffin ’85 and Wale Adebanwi, a professor at Oxford University.

Today, the department has the largest African languages program in the world, 41 full-time faculty members, more than 40 undergraduate concentrators, and 35 doctoral candidates.

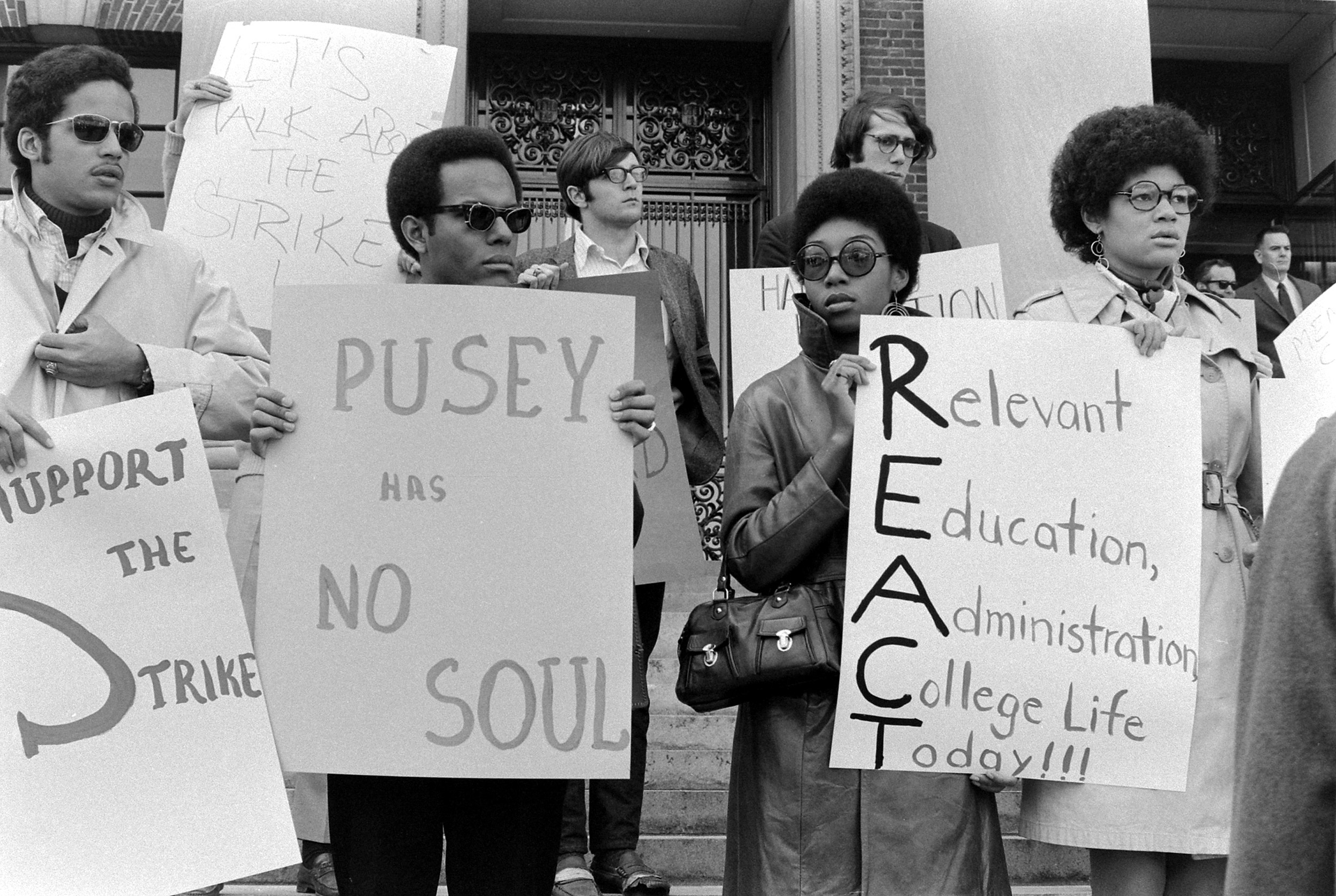

Its origin story began with student-led demands for change at all levels of the University. In 1968, an ad hoc committee of black students negotiated with University leadership on a path forward. After further protests and changes to their requests, the faculty approved the students’ demand to establish the department. The first class of 14 Afro-American Studies concentrators graduated in 1972; the graduate program was developed in 2001, and African Studies and African American Studies merged in 2003.

Student activists at Harvard Stadium, April 14, 1969.

Getty Images/Life Magazine

In his 1985 report for the Ford Foundation on the first decades of the department and the struggle for black studies across U.S. campuses, historian and former Afro-American Studies department chair Nathan I. Huggins wrote: “The demand of black students was for a discussion of what they saw to be the inherent racism in … normative assumptions for a shift in perspective that would destigmatize blacks and reexamine the ‘normalcy’ of the white middle class.”

This reexamination came in the form of new courses and areas of study that examined the African American experience across history, literature, sociology, and other humanities and social sciences fields. In its first year, the department offered 25 courses. This year students can choose from more than 200, including 18 African language classes.

The department was at the forefront of major Harvard milestones in the 1970s and the 1980s, including the hiring of musicologist Eileen Southern, who served as department chair for four years in the 1970s and was the first black woman granted tenure at the University. But it also faced challenges such as declining concentrator numbers and a lack of tenured faculty members, due to the complications of hiring established scholars in an emerging discipline.

By the mid-1990s, the department looked very different than it had a decade earlier. There were more than five tenured faculty members, including Gates, historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, sociologist William Julius Wilson, and philosophers Kwame Anthony Appiah and Cornel West.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. was one of the five foundational tenured faculty members of the department.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

“I say that the ‘church’ of Harvard’s African and African American Studies Department was designed by Kwame Anthony Appiah, Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, and [Lawrence] Bobo, but our pews were filled by Cornel West,” said Gates.

Henry Rosovsky, Geyser University Professor, Emeritus, in the Department of Economics, who served as chair of the faculty committee on African and Afro-American Studies in the late 1960s, credited Gates and former Harvard President Derek Bok with being instrumental to the growth and success of the department.

Neil Rudenstine, who was president of Harvard from 1991 to 2001, also highlighted the importance of Gates’s recruiting top talent throughout the 1990s. He said the visibility of AAAS illustrates its important role as an intellectual and cultural cornerstone of the Harvard experience.

“It was really [Gates’s] vision and the people he brought with him who made the whole thing work, because they had the sense that they were like everybody else in terms of what they wanted for Harvard, and what they wanted for the department,” said Rudenstine. “They did not want to be an enclave that was to be separated out [from the rest of the School]. They wanted their own identity that was special, but they wanted to be integral to the place. The impact was profound, and there was a sense that something had been created, which was not just unusual but really extraordinary, and it was deeply felt throughout the institution.”

Harvard students hold posters during the 1969 protest on the steps of Widener Library.

Getty Images/Life Magazine

Gates also pointed to the work and support of others, including former President Drew Faust, former Edgerly Family Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences Michael D. Smith, and Harvard students who lobbied for change throughout the department’s existence, for playing key roles in the growth and development of AAAS.

“Having the president behind you gave all the right signals throughout the University that this was not a token effort. This had nothing to do with making noises about ‘diversity.’ This was a very genuine intellectual commitment,” said Gates.

Today, the department’s influence can also be seen across Harvard in spaces including the Hutchins Center for African American Research and the Cooper Gallery of African and African American Art. Multiple faculty members hold chair appointments and deanships across the humanities and social sciences, including Edgerly Family Dean of Arts and Sciences Claudine Gay, who is a professor in AAAS and government, and Lawrence D. Bobo, W.E.B. Du Bois Professor of the Social Sciences and divisional dean of social sciences, a former AAAS Department chair.

“It is obvious that African and African American Studies is now recognized as a successful department” both at Harvard and in wider scholarly communities, said Rosovsky.

Rudenstine echoed the sentiment, saying, “I think there cannot be any question that what happened at Harvard made a difference to African American studies nationally.”

In addition to its standing in the field, the department has also been integral to student life on campus. For Sangu Delle ’10, the department was a crucial social and intellectual space while he was an undergraduate living far from his home in Ghana.

“Having the president behind you gave all the right signals throughout the University that this was not a token effort. This had nothing to do with making noises about ‘diversity.’ This was a very genuine intellectual commitment.”

Henry Louis Gates Jr.

“The AAAS Department played multiple roles for me. It was my academic home, but more than that, it was a place where I really felt at home as a student of color,” said Delle, an entrepreneur and clean-water activist who received a bachelor’s degree in African studies. “Beyond having the world-class faculty and access to resources, what differentiated the department were the additional benefits of having so many faculty of color who could be great advisers. Many students have an emotional, sentimental attachment to the department that you would probably not find in many other places.”

Delle, who also received a law degree and M.B.A. from Harvard, was one of the first students to participate in the department’s Social Engagement Initiative, launched in 2006 under the direction of Higginbotham, Victor S. Thomas Professor of History and of African and African American Studies. The program served as a way to bridge intellectual pursuits and civic responsibility for students in the department through coursework and theses.

“The scholarship that came out of the Social Engagement Initiative is rooted in transforming communities, being embedded in them, and implementing intellectual questions” learned in academic environments, said Higginbotham, pointing to successful thesis projects in places as diverse as Zimbabwe and Detroit, by students with strong connections to the communities in which they worked.

“The department was founded out of a demand for scholarship on the conditions of black people in the United States and around the world, and more scholarship that could be useful in our communities,” said Higginbotham. The Social Engagement Initiative and other community-based scholarship in the department are examples of ways for students “to be successful and do good. We can be generous in helping others with our expertise, and social engagement gives a way to bring knowledge to people on their terms.”

As the department celebrates its history, students and faculty are also looking to the future of the discipline and its place at Harvard, as the political and academic landscape shifts again.

“We’ve moved beyond the debate over legitimacy for the field in academia, and I want to turn our attention to questions of training, curriculum development, and methodology,” said Shelby. “I’m hoping this event can be an opportunity to talk about some of those things with people in the field, from Harvard and outside. It’s the beginning of a dialogue.”