Professor of Human Evolutionary Biology Joseph Henrich and his collaborators explored the impact of a ban instituted by the Roman Catholic Church in the Middle Ages.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

Targeting incest and promoting individualism

How a Roman Catholic Church ban in the Middle Ages changed extended family ties, as well as values and psychology of individuals in the West

If you’re from a Western society, chances are you value individuality, independence, analytical thinking, and an openness to strangers and new ideas.

And the surprising reason for all that may very well have to do with the early Roman Catholic Church and its campaign against marriage within families, according to new research published in Science by Joseph Henrich, chair of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, and a team of collaborators.

“If you’re going to ask the rise-of-the-West question,” said Henrich, an author of the paper, “there’s this big unmentioned thing called psychology that’s got to be part of the story.”

About a decade ago Henrich coined the acronym WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic) to describe the characteristics of cultures that embrace individualism. And those groups were weird, which is to say unusual within the rest of the modern world’s substantial psychological variation. Most of the prior studies attempting to explain the discrepancies focused solely on geographic or ecological factors.

Henrich and his collaborators decided to look at how social groups mold the psychology and values of members, the most important and fundamental being the family.

“There’s good evidence that Europe’s kinship structure was not much different from the rest of the world,” said Jonathan Schulz, an assistant professor of economics at George Mason University and another author of the paper. But then, from the Middle Ages to 1500 A.D., the Western Church (later known as the Roman Catholic Church) started banning marriages to cousins, step-relatives, in-laws, and even spiritual-kin, better known as godparents.

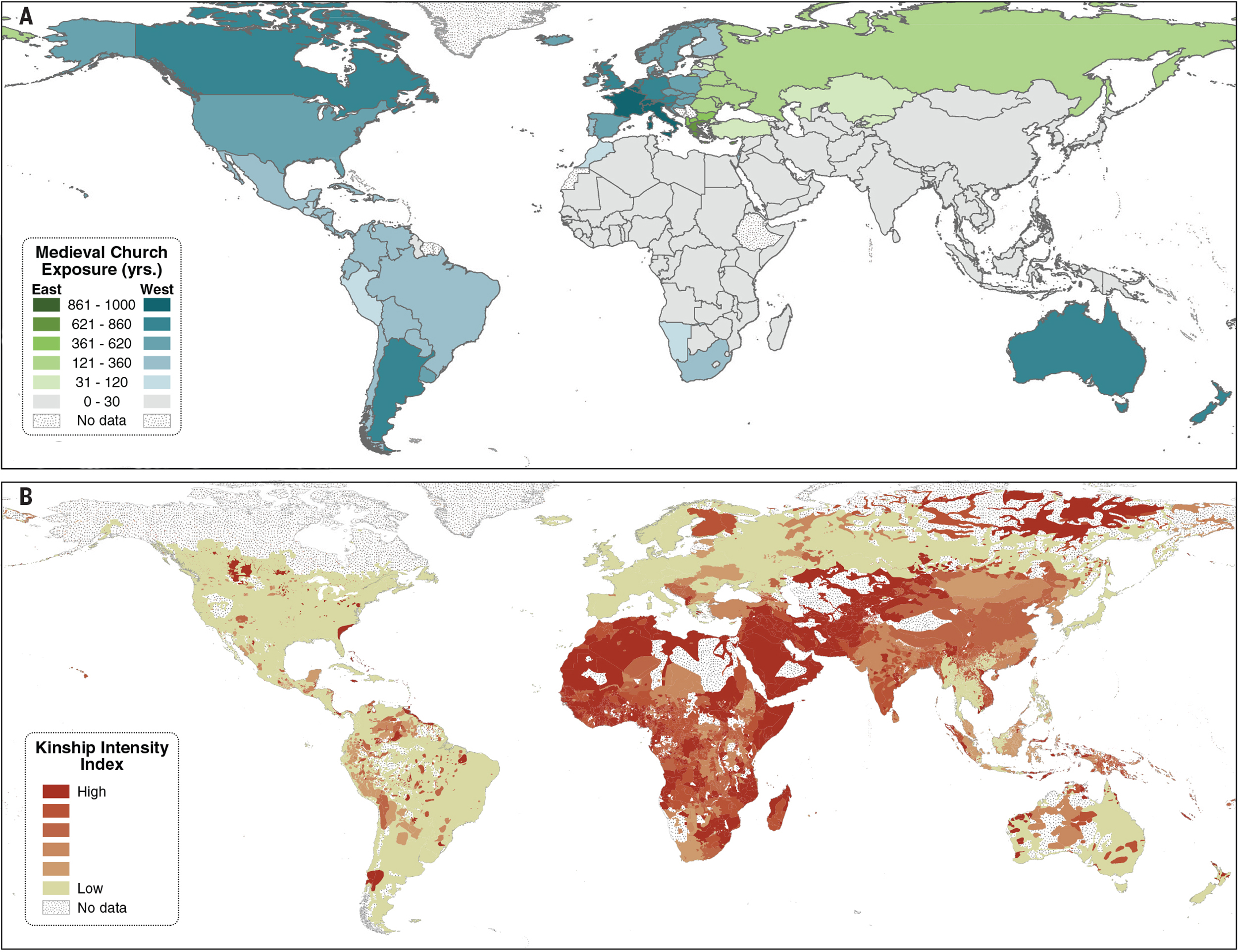

Church exposure and kinship intensity around the world. (A) Exposure to the Medieval Western (blue) and Eastern (green) Churches at the country level. (B) The Kinship Intensity Index for ethnolinguistic groups around the world.

Source: “The Church, Intensive Kinship, and Global Psychological Variation,” Jonathan F. Schulz, Duman Bahrami-Rad, Jonathan P. Beauchamp, and Joseph Henrich

Why the church grew obsessed with incest is still unknown. Co-author Jonathan Beauchamp, assistant professor of economics at George Mason University, suggests that one possible reason may have been material gain. Religious leaders could benefit financially from shrinking family ties — without a tight extended network those without heirs often left their wealth to the church. Whatever the reasons, one thing seems clear: The Western Church’s crusade coincides with a significant loosening in Europe’s kin-based institutions.

Comparing exposure to the Western Church with their “kinship intensity index,” which includes data on cousin marriage rates, polygyny (where a man takes multiple wives), co-residence of extended families, and other historical anthropological measures, the team identified a direct connection between the religious ban and the growth of independent, monogamous marriages among nonrelatives. According to the study, each additional 500 years under the Western Church is associated with a 91 percent further reduction in marriage rates between cousins.

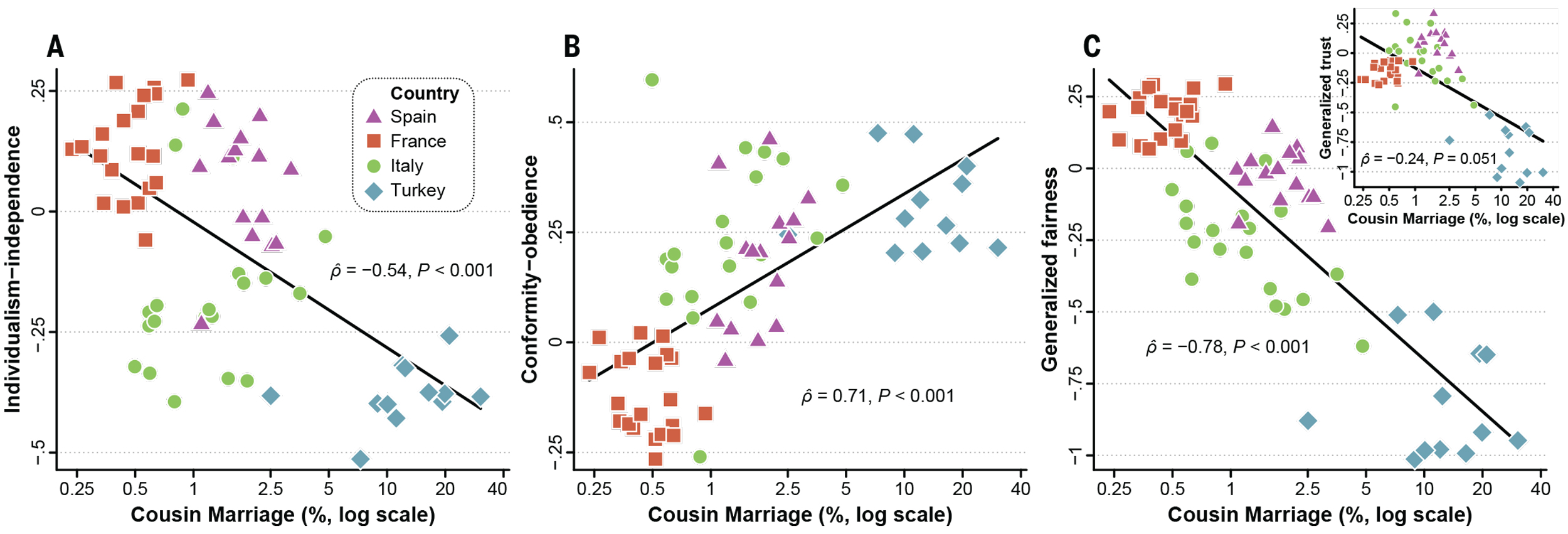

Relationships between regional estimates of cousin marriage and (A) individualism-independence, (B) conformity-obedience and (C) generalized fairness and trust. The shape and color of each data point indicates the corresponding country (see legend).

Source: “The Church, Intensive Kinship, and Global Psychological Variation,” Jonathan F. Schulz, Duman Bahrami-Rad, Jonathan P. Beauchamp, and Joseph Henrich

“Meanwhile in Iran, in Persia, Zoroastrianism was not only promoting cousin marriage but promoting marriage between siblings,” Henrich said. Although Islam outlawed polygyny extending beyond four wives, and the Eastern Orthodox Church adopted policies against incest, no institution came close to the strict, widespread policies of the Western Church.

Those policies first altered family structures and then the psychologies of members. Henrich and his colleagues think that individuals adapt cognition, emotions, perceptions, thinking styles, and motivations to fit their social networks. Kin-based institutions reward conformity, tradition, nepotism, and obedience to authority, traits that help protect assets — such as farms — from outsiders. But once familial barriers crumble, the team predicted that individualistic traits like independence, creativity, cooperation, and fairness with strangers would increase.

Using 24 psychological variables collected in surveys, experiments, and observations, they measured the global prevalence of traits that correspond or conflict with individualism. To test for willingness to help strangers, for example, they collected data on blood-donation rates across Italy, finding a correlation between high donation rates and low cousin-marriage rates. With their kinship intensity index, Schutz said, they can also predict which diplomats in New York City will or will not pay parking tickets: Those from countries with higher rates of cousin marriages are more likely to get a ticket and less likely to pay one.

And, although willingness to trust strangers, as opposed to family or neighbors, is associated with higher levels of innovation, greater national wealth, and faster economic growth, which factor causes which is not yet known.

“We’re not saying that less-intensive kin-based institutions are better,” said Beauchamp. “Far from it. There are trade-offs.” Tight families, for example, come with inborn financial safety nets.