At a recent Radcliffe talk, biographers Robert Reid-Pharr (from left), Tomiko Brown-Nagin, and Imani Perry explored how their subjects helped shape conversations around black politics, community, identity, and life.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Writing Black lives

In Radcliffe discussion, biographers reflect on their art

Constance Baker Motley, a pioneering lawyer, politician, activist, and the first Black woman appointed to the federal judiciary, “is one of the legal architects of postwar, Civil Rights-era America who made it possible for us to be here today,” said Tomiko Brown-Nagin at a recent Radcliffe discussion.

But Motley is hardly a household name, even though she argued the groundbreaking Brown v. Board of Education case before the Supreme Court along with Thurgood Marshall, and represented Freedom Riders and Martin Luther King Jr., among other accomplishments. With her latest book project, Brown-Nagin, dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study and the Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law at Harvard Law School, is hoping to change that.

“Motley certainly deserves a full biography,” said Brown-Nagin, who moderated “Writing Black Lives,” a talk by three biographers that explored how the life and work of Motley, playwright Lorraine Hansberry, and author James Baldwin have helped shape the contemporary conversation around Black politics, community, identity, and life. “She was amazing; she was complicated, including because of the way in which she experienced and represented her gender. So there is so much to learn from Motley, and from all of these wonderful African American figures.”

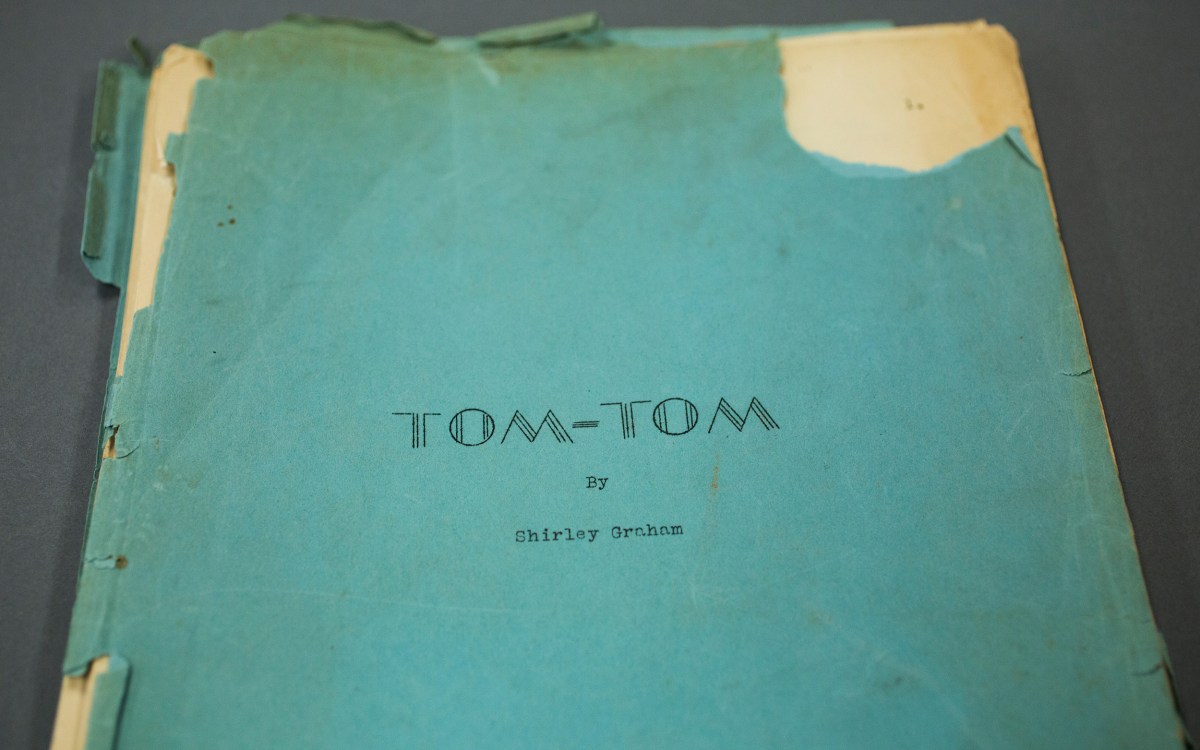

As part of their research, Brown-Nagin, Imani Perry, Princeton professor in African American studies and author of “Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry,” and Harvard’s Robert Reid-Pharr, who is working on a Baldwin biography, have spent countless hours poring through archives. Last week they produced some of their finds, letters and notes that highlighted the character and conviction of their subjects, as well as the challenging political and social context of their times.

Judges tend to avoid keeping papers or correspondence that might “reveal their thought process,” said Brown-Nagin, who is also a professor of history in Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences. Still, Motley, who died in 2005, saved a number of “gems” such as notes from activists Pauli Murray and King, who congratulated her on being appointed to the federal bench in 1966. “And then there are different kinds of letters,” said Brown-Nagin. She read the words of a white woman angry with Motley’s position and pay: “Very soon negroes are the masters of white Americans. Negroes even want to be president of the United States … No nation on earth can live in peace with two different colors, black and white.”

Such letters, said Brown-Nagin, help reinforce the notion that, “Even as we are writing about a person, we are writing about a public, and the African American and American experience.”

Much the same could be said for chronicling the life of Hansberry. The writer who penned “A Raisin in the Sun,” the first play by an African American woman to appear on Broadway, changed the course of the nation’s theater history by introducing audiences to “representations of Black Americans that are serious, that are nuanced,” Perry said. Hansberry, a driven Civil Rights activist who “pursued her life, her creativity in an unapologetic fashion and also stayed committed to her politics,” reminds us of the “kind of people we are supposed to be.”

“Even as we are writing about a person, we are writing about a public, and the African American and American experience.”

Radcliffe Dean Tomiko Brown-Nagin

Through careful, close examination of Hansberry’s letters, diaries, memos to herself, even something as simple as a calendar entry for a dinner engagement, “a life emerges,” said Perry.

For Reid-Pharr, a professor of studies of women, gender, and sexuality and of African and African American studies, fascination with Baldwin’s life began in 1979 when he picked up the writer’s controversial second novel, “Giovanni’s Room.” Reid-Pharr was 14, and it was the first time he’d seen a book with a black face on the cover. Soon he’d read everything by Baldwin, including reflections on his Pentecostal background — a background they shared. It was another first for Reid-Pharr, who had never seen his world rendered in such detail and suddenly understood “the world in which I lived was a world that could be written about.”

Baldwin’s work, he added, “changed who I was as a human being. It got me on a path to being a person interested in literature and turning toward a literary critic.”

But writing a Baldwin biography hasn’t been easy. The New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture houses the official Baldwin archive, 30 linear feet and hundreds of thousands of pages of material that can’t be photographed or photocopied. (After more than two years of work Reid-Pharr has 700 transcribed pages.) It’s been a time-consuming process, but it’s also been enlightening, he said, bringing him closer to the true nature of the literary icon and social critic.

Reid-Pharr said it felt like a privilege to have “the materials of the maestro in your hand,” and that Baldwin is one of the intellectual giants of the American 20th century. But his research has also revealed the artist’s flaws. In today’s video-obsessed culture it’s easy to get a “YouTube version of Baldwin,” said Reid-Pharr. With his book he hopes to offer a more complicated, “grittier” version of the author and activist, one that examines his struggles with fame, celebrity, sexuality, and the responsibility of representing his race, one that can be “more useful to what we are going through now.”

Reflecting on the genre, Perry said she sees the biography as a chance to blend history with creativity.

“I, as a writer and a scholar, have been interested in how does one transition from a style of writing that’s primarily devoted to making people think to one that is also devoted to making people feel?” she said. “And there is something about the examination of a life on a material level that opens up that kind of space for emotional relevance.”