“Unite or Perish,” John Simmons, Chicago, 1968.

Courtesy of the artist

Taking it all personally

Carpenter Center show reflects racial disparities that helped fuel James Baldwin’s writing

James Baldwin’s 1964 essay “Nothing Personal” critiqued a country divided by suspicion, greed, hatred, fear, violence, oppression, and racism. But it also acknowledged the light in humanity. More than 50 years later, it remains relevant and fresh.

Now through Dec. 30 at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for Visual Arts, a series of photos shines a light on the America the author and social critic was responding to with his words, as well as on the present climate. “Time is Now: Photography and Social Change in James Baldwin’s America” tracks the context of the author’s life and the social unrest that drove his writing. Like Baldwin’s prose, it reflects turbulent times.

“I wanted to do something that would picture in words and objects … Baldwin’s life and also be a space for people to see the actual world that he lived in and the kinds of issues that he was interested in,” said Makeda Best, who curated the show that draws from the permanent collections of the Harvard Art Museums. The exhibit is the Carpenter Center’s response to Teresita Fernández’s October installation in Tercentenary Theatre, “Autumn (… Nothing Personal),” which drew on Baldwin’s writing for inspiration.

“That affected me as a young person when I read Baldwin’s writing, that interest in everyday people,” said “Time is Now” curator Makeda Best.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

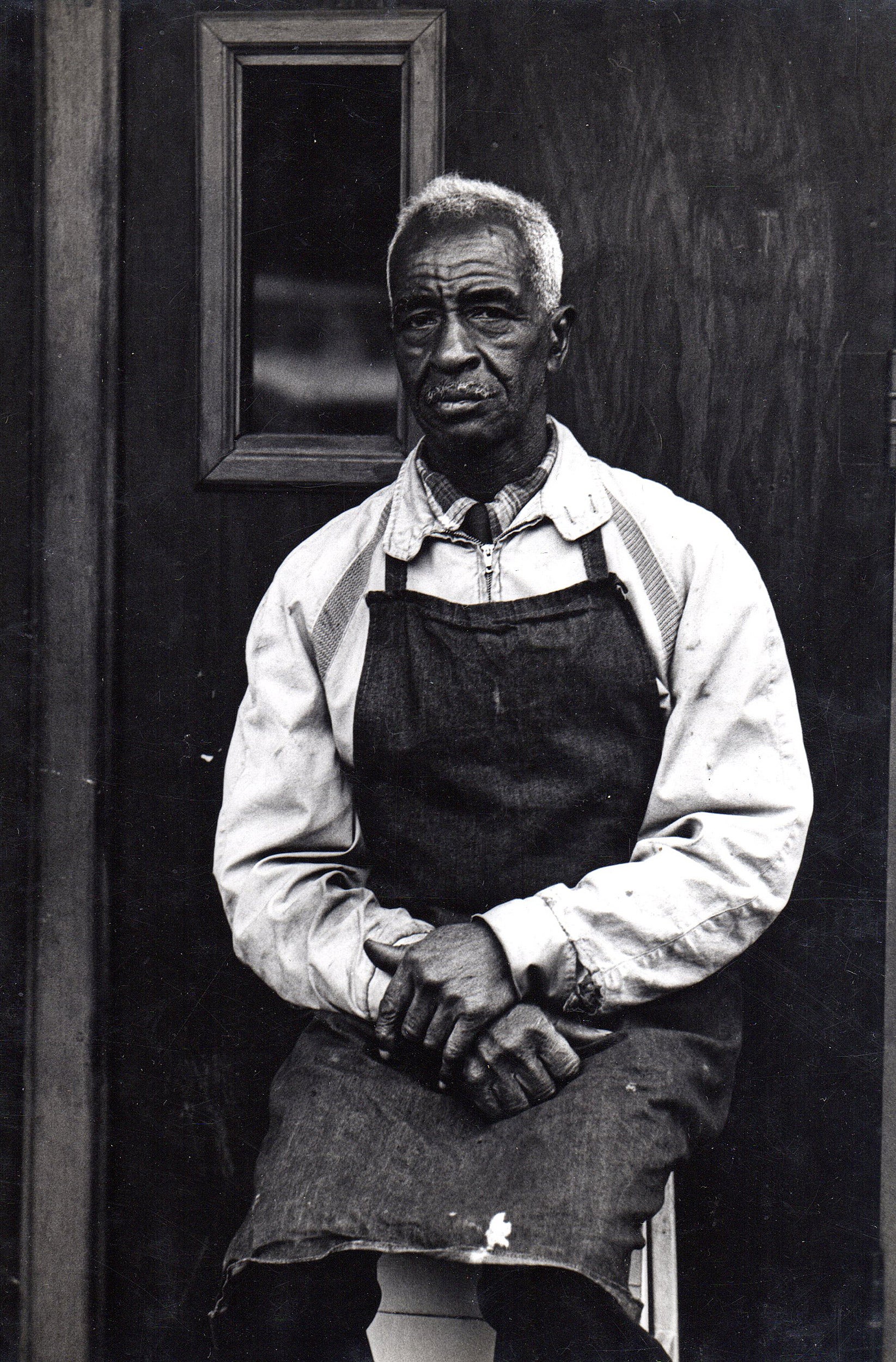

“Nothing Personal” is also the title of a 1968 book that blended Baldwin’s biting essay with selected photographs by his friend Richard Avedon. In one of the show’s two glass cases, the book lies open on a page containing Avedon’s 1963 portrait of elderly William Casby, one of the last men born into slavery in the U.S.

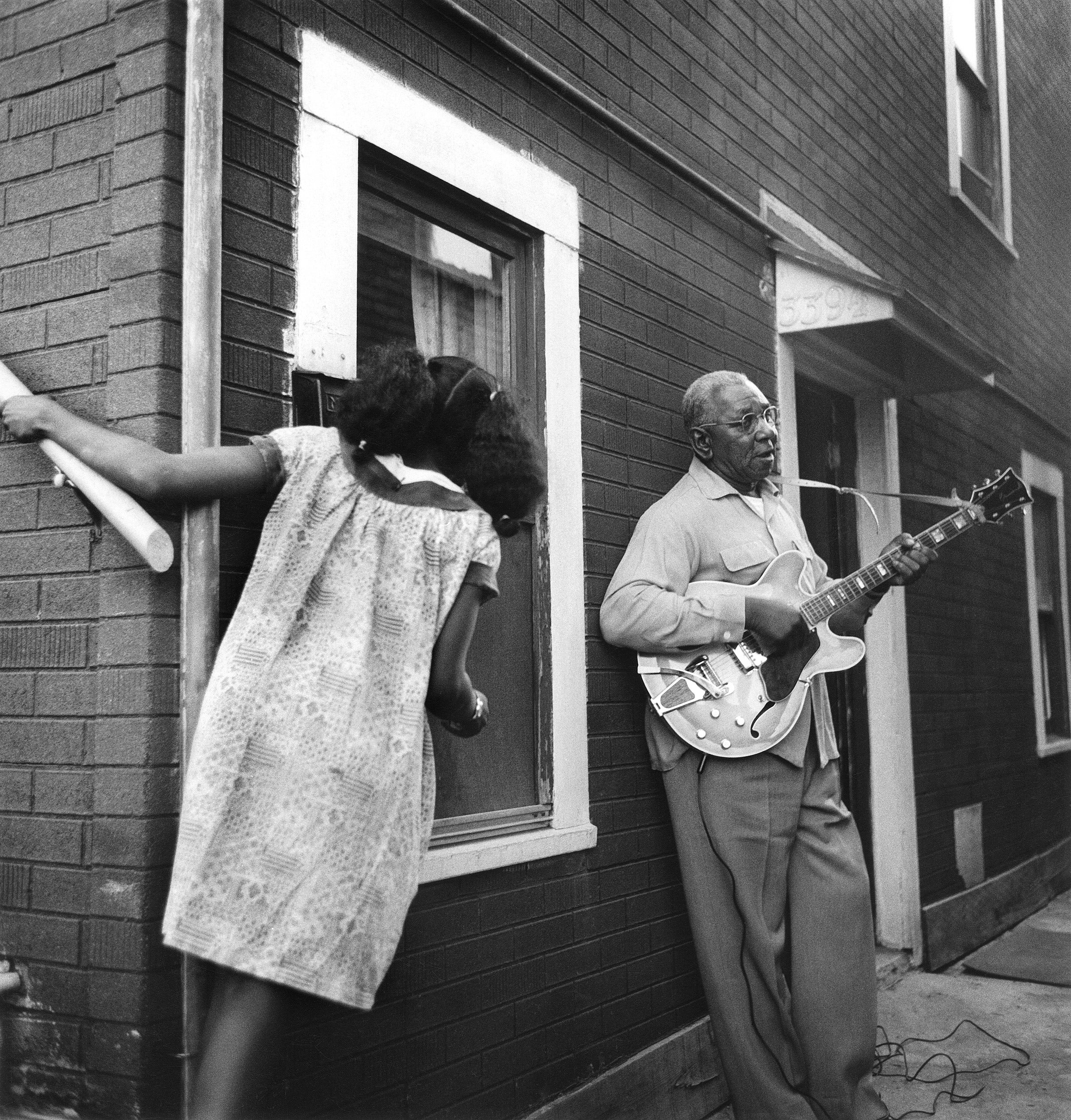

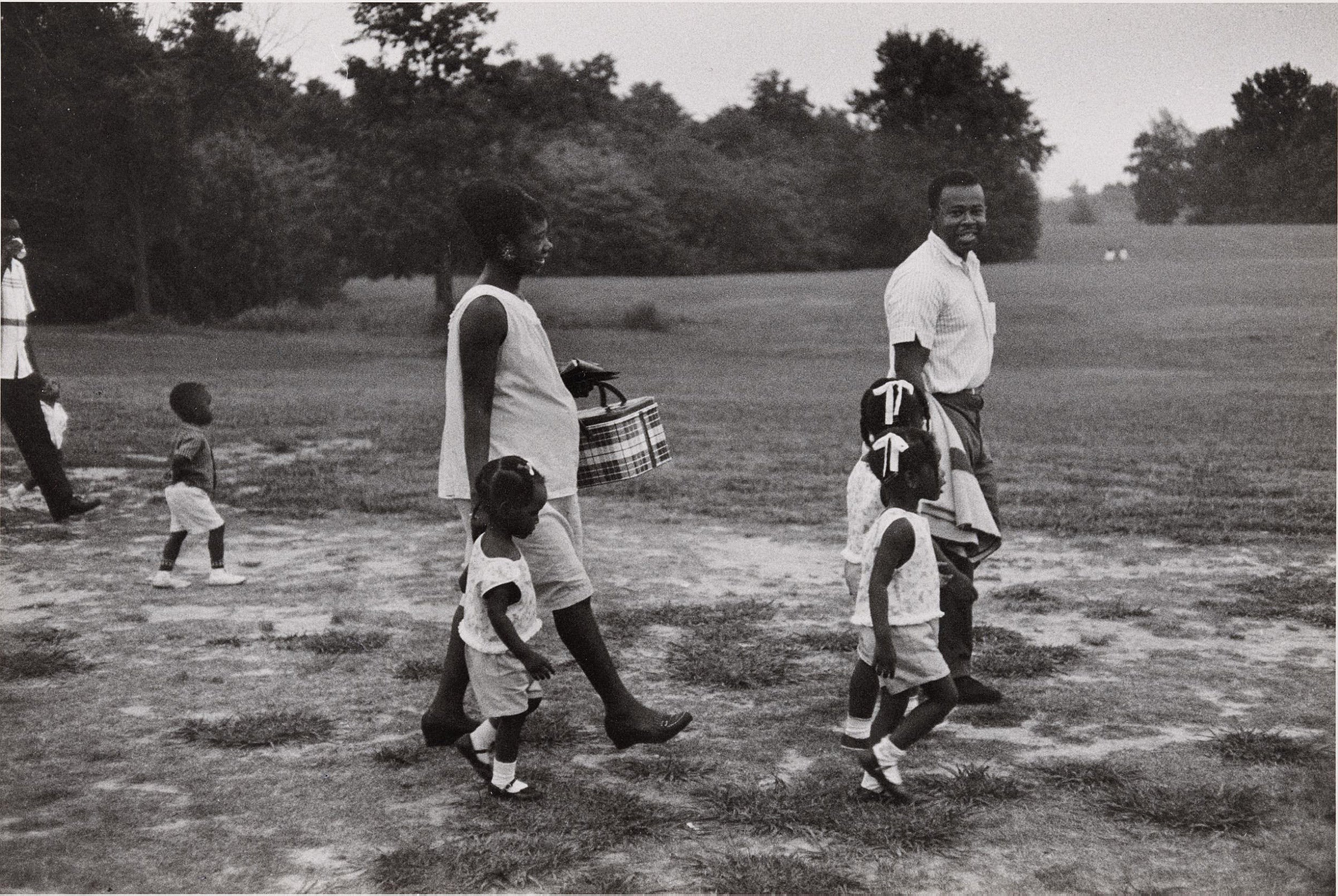

Avedon’s work rests in good company. The exhibit features photos by Dawoud Bey, Diane Arbus, John Simmons, Ben Shahn, and Marion Post Wolcott. Seen together, the images create “a rich repository of images of American life,” said Best. Much of that richness is captured in photos of the everyday, a familiar subject for Baldwin and Avedon, and an underlying theme of the show.

“That affected me as a young person when I read Baldwin’s writing, that interest in everyday people,” said Best, Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography, who first encountered his work as a teenager in San Francisco. “And that’s something that interested me in photography, so I wanted to bring those both together.”

Aside from a photo of the author, the pictures on the walls represent average men, women, and children. Their anonymity honors the social documentary tradition of “elevating the experiences of everyday people,” said Best, and reflects Baldwin’s own fascination with how the everyday “perpetuates various aspects of history.”

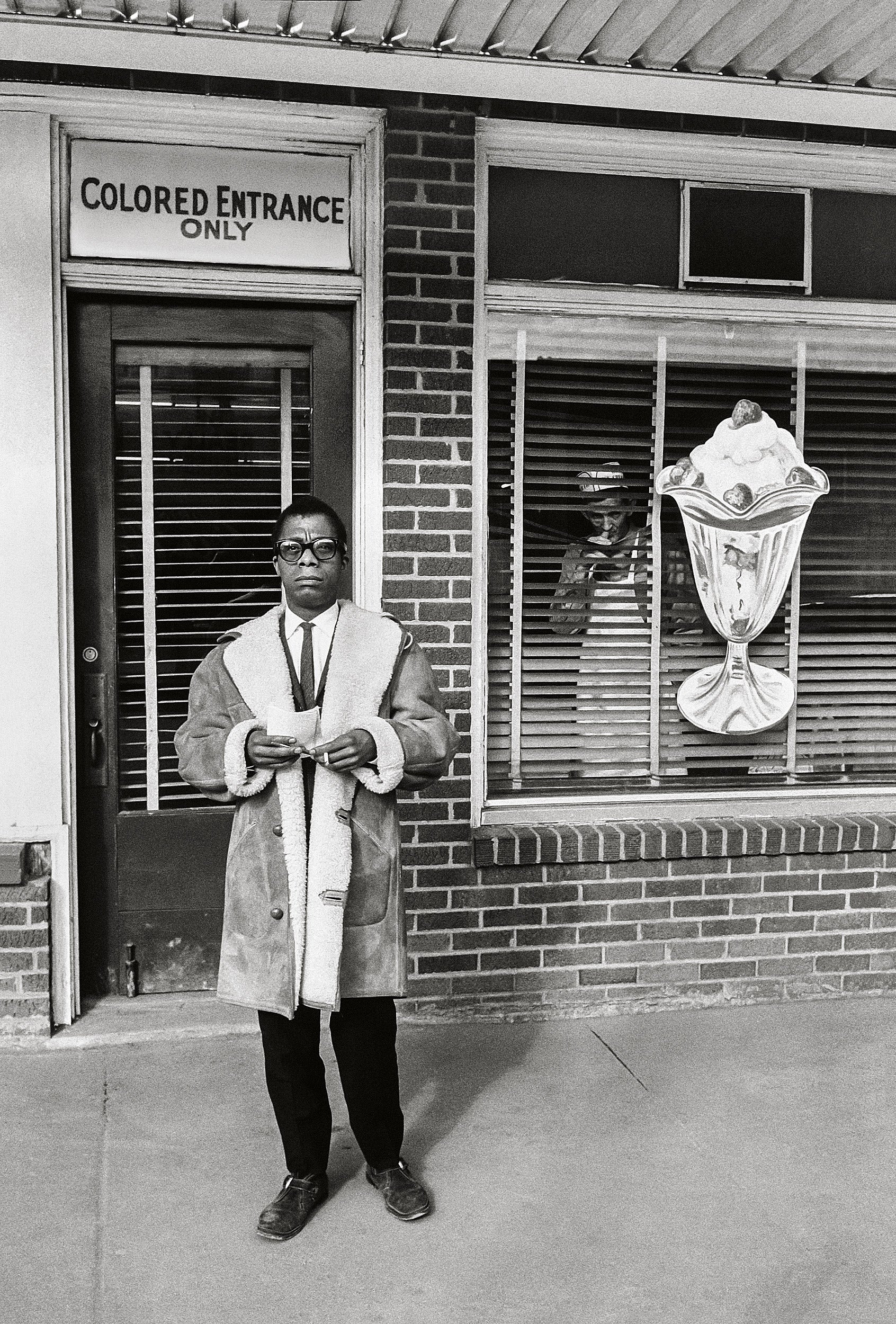

“James Baldwin, Colored Entrance Only, New Orleans,” Steve Schapiro, 1963.

Courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

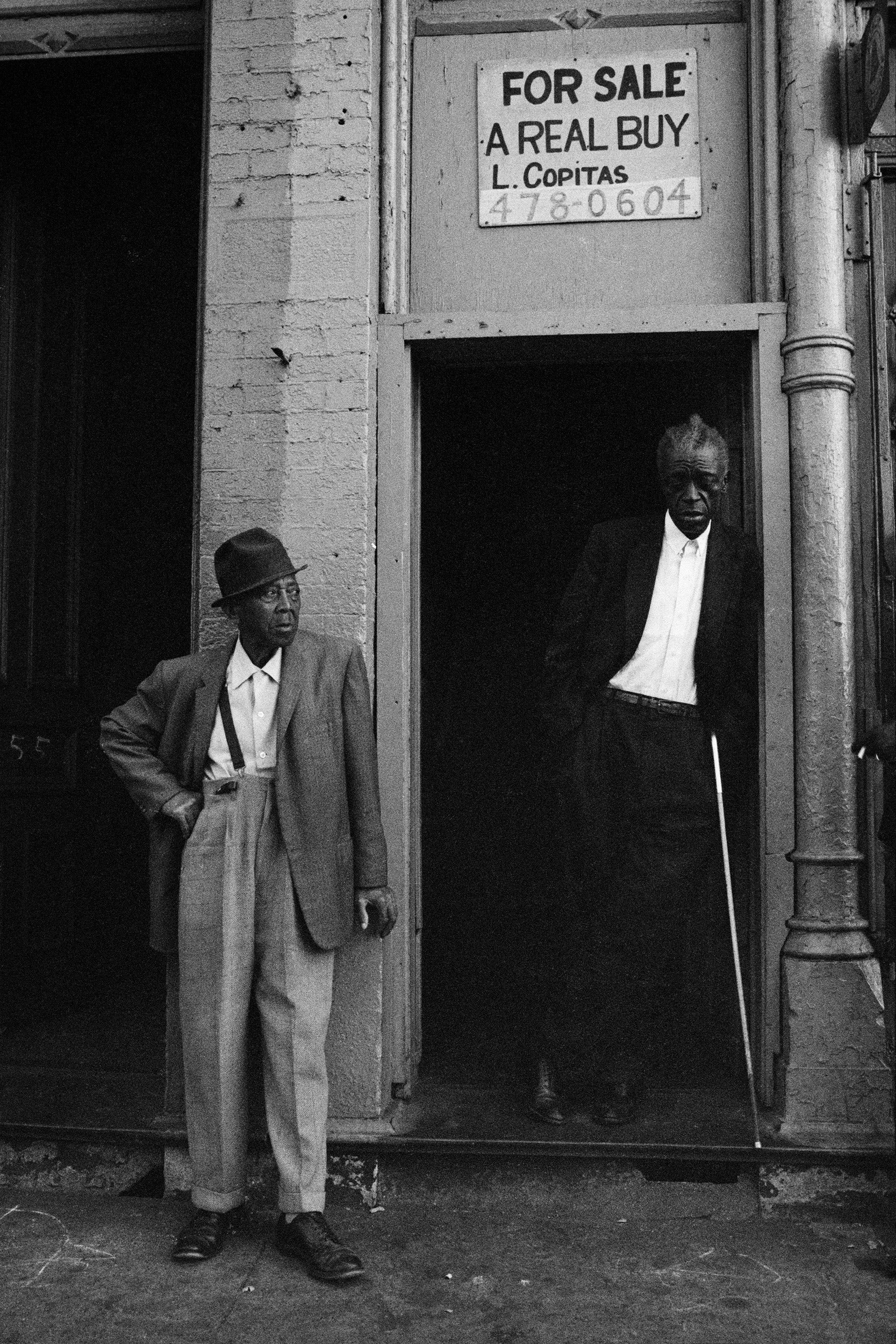

Untitled images by John-Simmons (1966) and Joanne Leonard (1965).

Courtesy of the artists

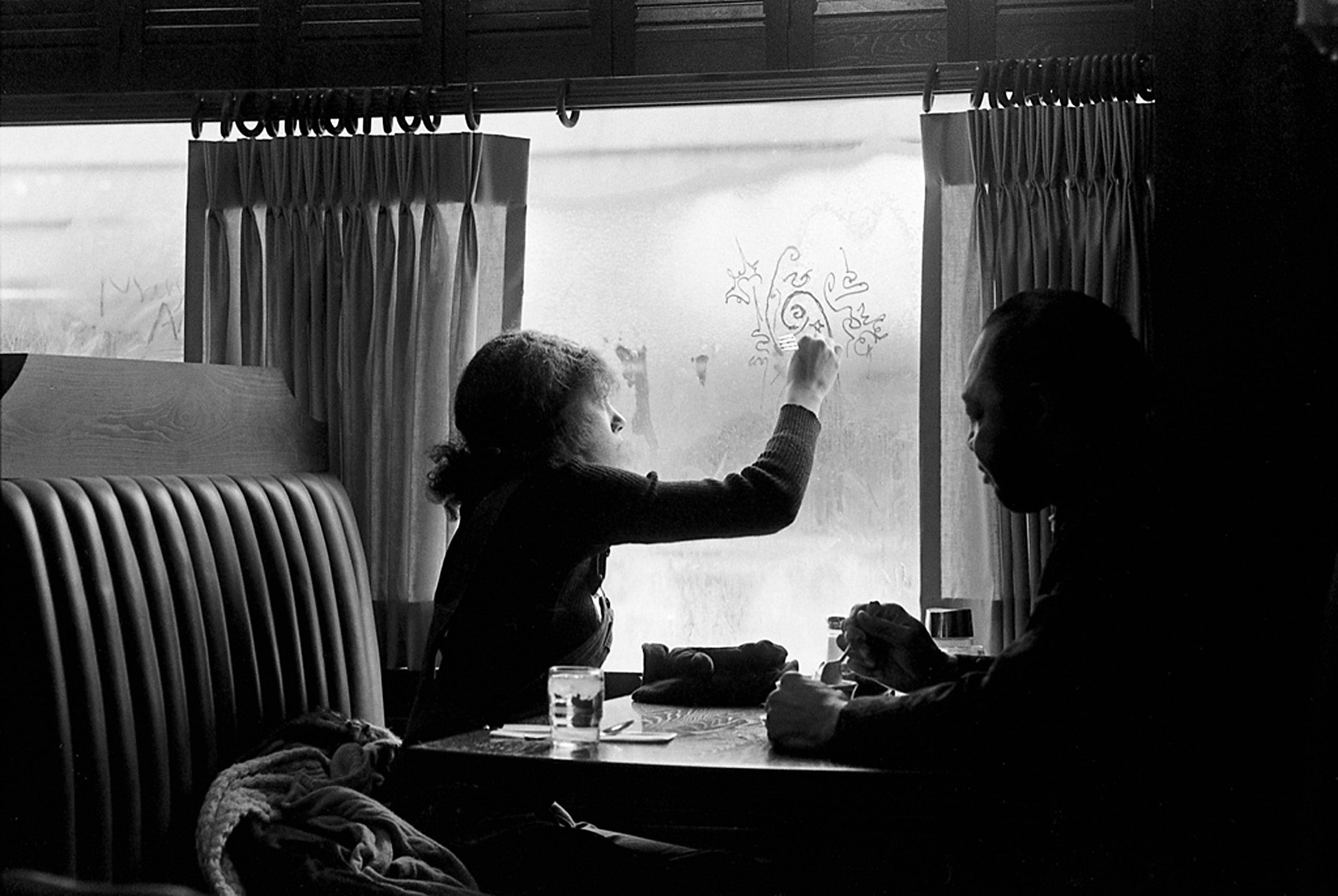

“Window Writing, Chicago,” John Simmons, 1969.

Courtesy of the artist

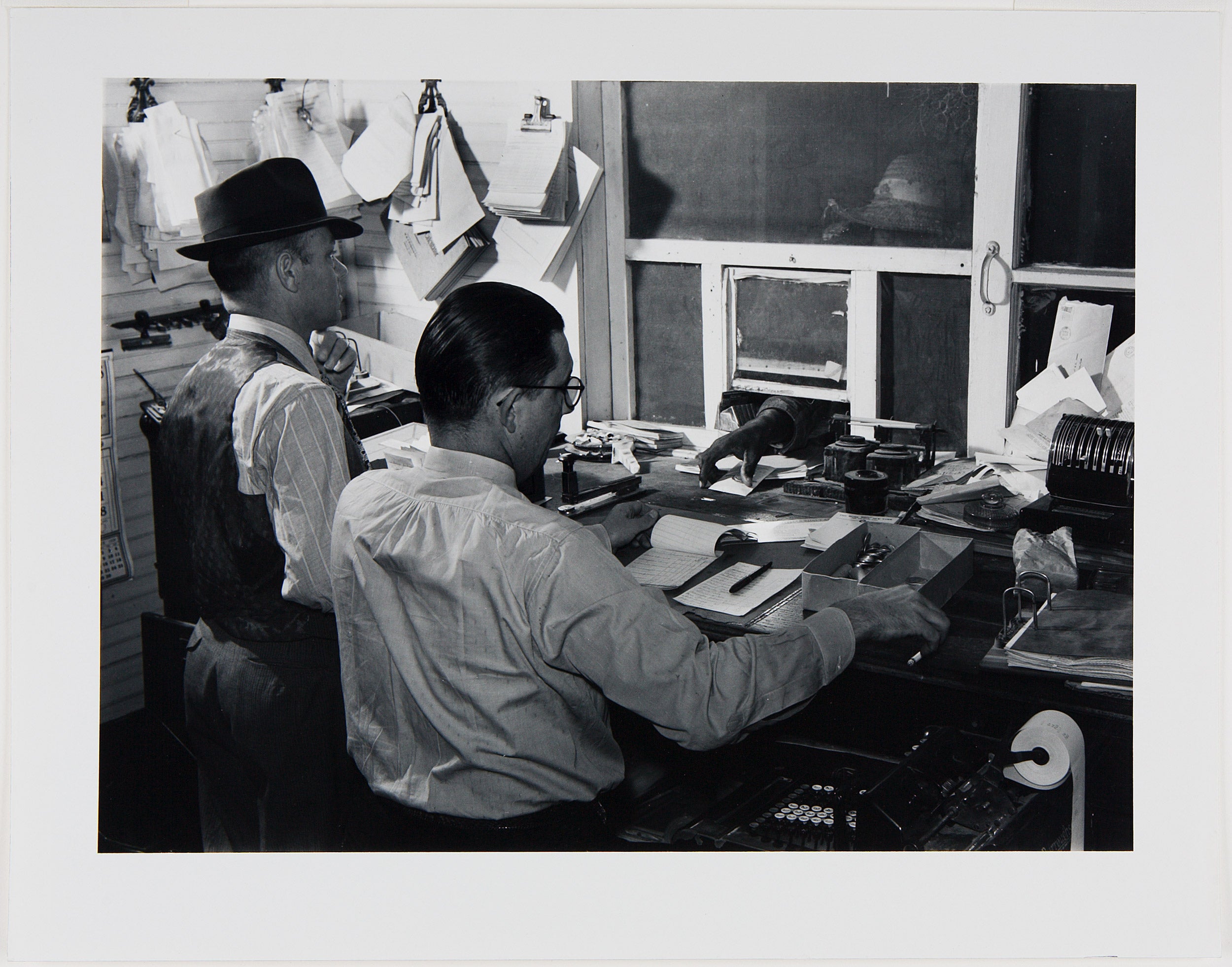

Wolcott’s 1939 photo titled “Cashiers Paying Off Cotton Pickers, Marcella Plantation, Mileston, Mississippi” perhaps best epitomizes that tradition. The black-and-white picture shows an African-American woman reaching her hand through a window to retrieve her meager earnings as two white men on the other side of the desk look on. That simple action “encapsulates a kind of history of injustice and a kind of way people were humiliated and a way in which racism lives in everyday gestures,” said Best.

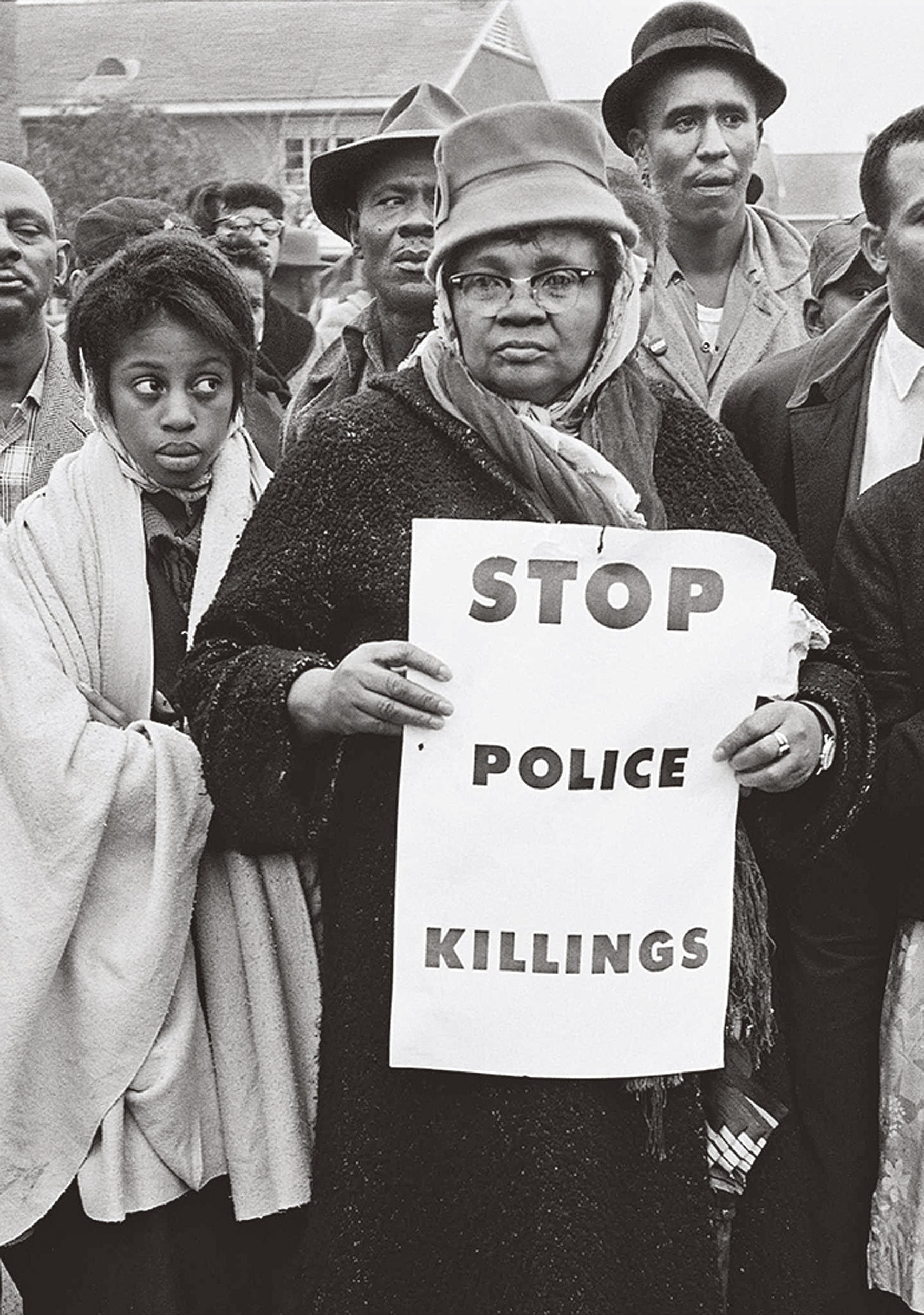

Slavery haunts several other photos, such as a shot of men on a chain gang, an image of minstrel show performers (one in blackface, another wearing a Native American headdress), and a picture of adjacent water fountains labeled “colored” and “white.” Photos that evoke the Civil Rights era and the recent Black Lives Matter protests include Simmons’ picture of black protesters marching in Chicago in 1968, bearing signs that read “Unite or Perish” and “America is the black man’s battleground not Vietnam,” and Steve Schapiro’s 1965 shot of an African-American woman in Selma, Ala., holding a poster that says “Stop Police Killings.”

The title of the show comes from Baldwin’s answer to a question about when to take up activism. He responded that “The time is always now,” said Best, adding that the show is also deeply informed by Baldwin and Avedon’s understanding of the phrase “nothing personal.” At the time, both men knew it “was a very resonant phrase, it was a very aggressive phrase,” said Best. “And I think that they are actually saying that we should take all this personally. All of what we’ve seen and all that’s happening is personal, and it impacts our history and our common bonds as Americans.”

The Harvard Art Museums will present a screening of director Barry Jenkins’ “If Beale Street Could Talk,” an adaptation of James Baldwin’s novel of the same name, on Thursday, Nov. 29. The screening is being offered in conjunction with the exhibition “Time is Now: Photography and Social Change in James Baldwin’s America,” at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts through Dec. 30.

Share this article

“Cashiers Paying Off Cotton Pickers, Marcella Plantation, Mileston, Mississippi,” Marion Post Wolcott, 1939.

Courtesy Harvard Art Museums © President and Fellows of Harvard College

Untitled photo (Tennessee, 1962) by Bruce Davidson.

Courtesy Harvard Art Museums

“Stop Police Killings, Selma,” 1965, Steve Schapiro.

Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

“Mr. Johnson, seated; Blake Avenue, New York,” 1965, Frank Espada; “A young Negro boy, Washington Square Park, N.Y.C. [Black boy, Washington Square Park, N.Y.C.],” 1965, Diane Arbus.

Courtesy of Frank Espada; Harvard Art Museums