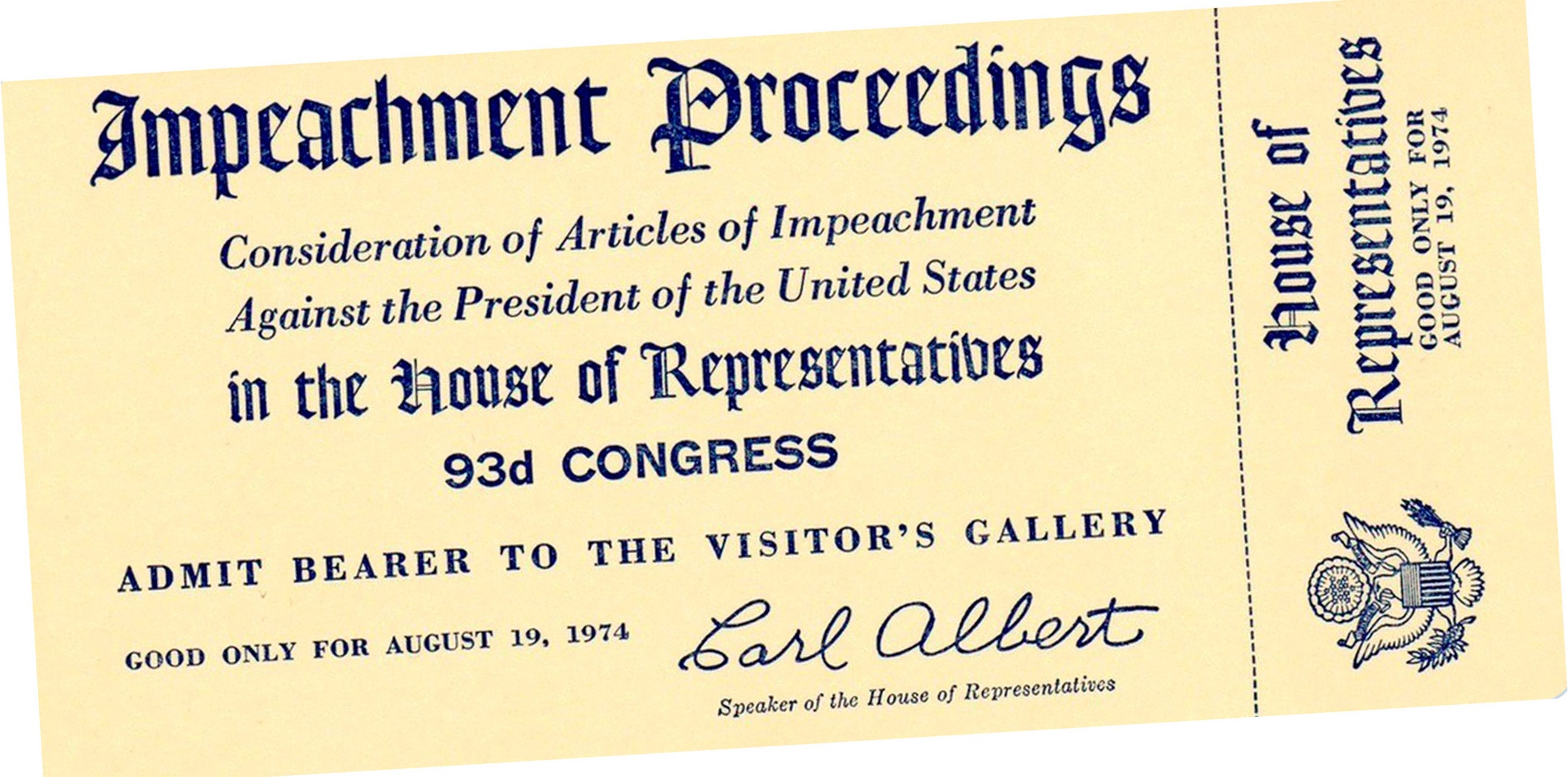

The House Judiciary Committee in deliberations leading to the vote for impeachment of President Richard Nixon for obstruction.

Everett Collection Historical/Alamy Stock Photo

Clinton, Nixon, and lessons in preparing for impeachment

Veterans of past battles offer insiders’ looks into the politics, procedure, and strategy of investigators and lawmakers

Past isn’t always prologue, but it can be a useful guide when navigating murky, unfamiliar waters like the possible impeachment of a U.S. president. With President Trump facing an inquiry in the House of Representatives after disclosures that he asked the president of Ukraine to investigate a political rival, the Gazette asked a handful of Harvard graduates who played key roles in the cases against Presidents Nixon and Clinton for their insights. Some served as attorneys investigating Nixon (Evan Davis, James Reum), voted on articles of impeachment as House Judiciary Committee members (Reps. Elizabeth Holtzman, Barney Frank), or became a vigorous public voice for impeachment in the media (Bill Kristol). They discussed what happens off-camera during an inquiry, rate how Trump, Republicans, and Democrats are doing so far, and what lessons today’s lawmakers can take from the experience of the past.

What goes on during an inquiry? We see subpoenas for documents and witness testimonies, but what else is happening behind the scenes?

Evan A. Davis ’66

Counsel for House Judiciary Committee impeachment inquiry (1974)

Senior counsel, Cleary Gottlieb

I coordinated a group of six or seven staff lawyers, and we were working on assembling and marshaling the facts related to Watergate and the cover-up. We were looking very closely at the Senate Select Committee testimony from the year before, various documents, some tape recordings as they came in. We interviewed some witnesses like John Dean, and we were looking at the facts so we could present those facts to the committee.

The two important things to remember about how the committee framed articles of impeachment: First, they did not rely on a single event. For example, there was the payment of hush money to Howard Hunt on March 21, 1973. There was a lot of factual support that had been sent over by the special prosecutor’s office that had come before the grand jury about the president’s approval of that payment. But we didn’t rely on one particular fact. Rather, we relied on a series of facts that showed a long train of violation, a long train of obstruction of justice, a long train of abuse of power, a course of conduct over time. The articles that were ultimately voted on by the committee had this course-of-conduct approach.

The first article of impeachment was about obstruction of justice, which is a crime, of course. The second article of impeachment, though, was about abuse of power. The things that were talked about there were not crimes. One of the takeaways from the way the articles were developed is that it does not have to be a crime in order to be an impeachable offense.

James M. Reum, J.D. ’72

Counsel for House Judiciary Committee impeachment inquiry (1974)

Partner, Winston & Strawn (retired)

It was something that everybody in fact took very seriously. It was a major constitutional undertaking that really needed to have key elements of nonpartisanship and fairness. And honestly, even though it sounds like it’s too idealistic, especially in present times, that really did permeate the whole process. First of all, there was a serious vote of the whole House of Representatives to undertake the impeachment inquiry, which I personally think is still an important requirement. There were a lot of procedural safeguards put in place so that along the way it was conducted with fairness and in an orderly, methodical way.

I was looking particularly at the improvements that were made at Nixon’s homes in San Clemente, Calif., and Key Biscayne, Fla. I was one of the few who went out and did field work and interviews and so forth. The other area I was less involved in was the donation by President Nixon of his papers, that he had an IRS write-off that had allegedly been backdated. Those were written up and submitted as reports, and then it was determined and judged which of those were serious enough to present to the committee as potential articles of impeachment.

It was basically about eight months in which you never came up for air. We were working around the clock, and the pressure [was intense]. But the gravity of it all really hits you because it’s something so unusual and historic that it sobers you up pretty quickly.

What standard of proof or confidence level in the underlying evidence was needed in order for the Judiciary Committee to decide which articles merited bringing forward for a floor vote?

Elizabeth Holtzman ’62, J.D. ’65

Representative from New York’s 16th Congressional District (1973‒1981)

House Judiciary Committee member (D)

A rough analogy is a grand juror. You have to be satisfied in your own mind. I don’t think we adopted any specific standard. Since this is not a criminal matter, obviously the ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ standard doesn’t apply. But I think you want to have a standard of clear and convincing evidence. You don’t want to railroad somebody without clear evidence. I think there’s no question that there appear to be grounds for impeachment of this president for at least high crimes and misdemeanors, and possibly bribery. But that whole case needs to be brought into proper shape. And what I hope [is] that they have the proper counsel to deal with the impeachment inquiry, which would require people who are trained prosecutors, trained litigators, people who are familiar with putting together a major case, as opposed to dealing with policy issues, which is what committee staff normally do, to assemble the facts, to identify the loopholes and where you need to strengthen the case to get those additional facts, and to present it to the committee and then, ultimately, of course, to Congress and the American people.

House Republicans are now in the same boat that Democrats were during President Clinton’s impeachment — playing defense. What was that like?

Barney Frank ’61, J.D. ’77

Representative from Massachusetts’ 4th Congressional District (1981‒2013)

House Judiciary Committee Member (D)

At first, I was worried about it. [During the Nixon case], there was a Republican from New Jersey, [Rep. Joseph Maraziti,] he was a very vigorous defender of Nixon. He was sarcastic and angry and belittled the whole effort. He actually lost his seat that year. So I was very careful. There was a point at which I was one of the few willing to defend [Clinton]. The general assumption was that the public was going to be very angry at him. In fact, the day that it came out that he had to admit he had oral sex, that was the main item on all the newscasts. They asked me if I would be able to respond, the White House did, and I said, ‘Yes.’ And it turns out, I was like the only one who said yes. That night, I was on two or three networks and CNN.

So from that period on, I was nervous. And I said, “If I’m going to be maybe his most prominent defender, or one of his only defenders, I better do this in a respectful way. He didn’t do this, so I don’t want to make the mistake of that guy from ’74 of being abusive and dismissive of the whole idea.” And I was careful to do that, and I did stay that way for much of it. I still saw myself as being somewhat politically at risk in this. Not that I would lose my seat, but that it would be unpopular. But I felt it was important to do. Then came that day when that testimony came out when he said yes, he had oral sex. The responses we were getting from people calling in was, “This is not a big deal; this is wrong to impeach,” and it became clear that was the reaction of the American public. So from then on, I became less worried and felt much freer to go on the offensive.

As the minority party, what tools did the Democrats have to thwart Clinton’s impeachment and what can House Republicans do now?

FRANK: One was ridicule, because of the nature of [the Clinton case]. And the other was procedural. They had the numbers, but they went in a very unfair way. They kind of steamrolled it. My advice to the Democrats this time is going to be, “You have the majority. Be very careful. Lean over backwards procedurally. Don’t let them argue that you’re being unfair.” We were able to argue correctly that they were being unfair. The ’74 impeachment had been very bipartisan. Our strategy was to focus on the fact that this was the only charge and to talk about how it wasn’t an impeachable offense, to offer a censure instead, and to make it clear that, unlike ’74, they were behaving in a very partisan fashion.

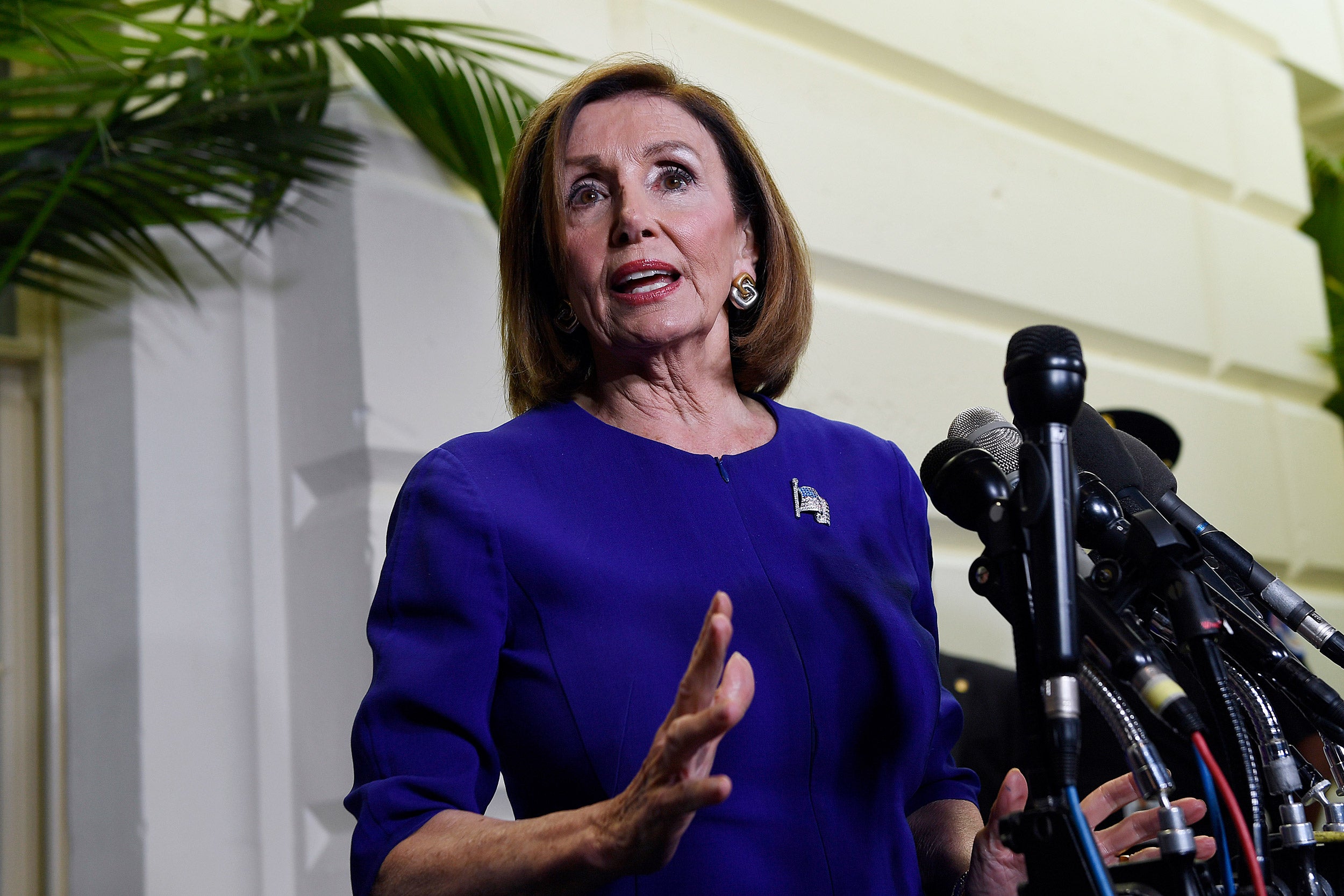

I think their best argument is: “This is an impeachment in search of a cause” [or] “The Democrats were just bent on impeaching him.” And that’s where Nancy Pelosi has put us in good shape because it’s very clear she did not want to impeach; she was holding off impeachment until this issue came up.

Clinton acted like impeachment barely existed and did everything to convey that he was focused solely on his presidential duties. Trump talks constantly about impeachment. Did that help Clinton minimize the charges in the minds of voters and will Trump’s chatter hurt or help by diluting the shock value of the charges and corroding the gravity of terms like impeach and treason?

Bill Kristol ’73, Ph.D. ’79

Political analyst, editor at large for The Bulwark

Founder and editor The Weekly Standard (1995‒2018)

On the first, the answer is certainly yes. Clinton did a good job of making it seem like this was a sidebar or side issue: “It may be unfortunate, but surely you’re not going to change the president of the United States for that.” On Trump, I don’t know. Yeah, he can muddy the waters a lot, and he can devalue terms like treason, but then at the end of the day, there probably will be a vote on the floor of the House, and there may be a floor vote in the Senate. I think senators are going to have to step up and say, “He didn’t do anything wrong.” Or, “He did some stuff, but it didn’t amount to impeachment.” Most senators aren’t going to sound like Trump’s tweets. So that’s why I’m a little dubious about this strategy. It probably keeps his base revved up, but I don’t know if it really works with the people he needs to have it work with. Maybe it holds enough of his base that he avoids getting to [the required] 67 [votes to impeach in the Senate].

How important is a president’s public messaging in defending against impeachment?

KRISTOL: I think most of it is the underlying facts. You can have all the messaging you want, but unless it comes out you ordered some White House aide to do something, as Nixon did on the tapes or in Clinton’s case, without any sort of broader, public malfeasance, messaging can only go so far. With Trump, attacking [Joe] Biden and attacking the press, “[Rep.] Adam Schiff [J.D. ’85] shouldn’t have dramatized the transcript” and all that kind of stuff, I’m actually a little doubtful that message is going to matter that much.

For those members of Congress who are on the fence, they’re going to be moved by [questions regarding] how much Trump really misused the instruments of government for his personal, political gain in a way that’s really unusual and [sets] a terrible precedent and opens us up to exploitation in terms of other countries and meddling in our elections and so forth. I think the reality does outweigh the messaging at that point. And I think we’ll know quite a lot in a month. The House will find out what they need to find out, and people will make a real judgment, and at that point, a lot of Republicans will stick with Trump. Democrats will be against him. But I think more Republicans will be on the fence than people realize.

How are Democrats doing so far and what mistakes do they need to avoid?

FRANK: Pelosi has been magnificent: first saying no and now saying yes, but focusing on this [Ukraine] issue. It’s the reverse, in this sense, of [Clinton], where the problem the Republicans had was they only had Lewinsky because Starr took away the other, more serious accusations. In this case, it’s Pelosi who’s dismissed the other accusations, but correctly, because they aren’t important enough, and so she’s established that it’s just this and allowed them to focus on this. And also, I think her obvious preference for Adam Schiff to handle this, that’s important because first of all, he’s a very good guy and is of the right temperament. [Rep.] Jerry Nadler is a good guy, but he has a very, very left-wing district that drove him, I think, to be in this whole impeach [mode] before it was a good idea. Schiff has a better district, but he is also a very sober guy. Also, by his taking the lead as chairman of the Intelligence Committee, he puts the focus on the national security aspect of this.

KRISTOL: I think they need to focus on the facts: “We want to get the facts; we’re not going to let him stonewall us.” It’s tough on the notion that stonewalling itself is impeachable, but I don’t think they need to worry. It’s unpleasant to get attacked the way they’re getting attacked. Trump wants to make it into some kind of “he said, she said,” so to speak, just a big mudslinging match. That would be a mistake for the Democrats to get into, and I think Pelosi understands this. They need to really focus on what he did. He’s the only president. Who cares if Adam Schiff is a good or great or mediocre committee chairman? That’s not the issue. They need to have that kind of attitude.

What did you take away from your experience that remains relevant to an impeachment now?

HOLTZMAN: Well, that [then-House Judiciary Committee Chairman Peter] Rodino was right in that the fairness of the process kept the focus on the facts. People weren’t always fighting over, “Well, I didn’t get my chance to speak here” and “I think we should’ve had this witness here.” None of those issues interfered. Everybody felt that the process was fair. They never attacked [it] as not being a fair process. That allowed Republicans to look at the facts and to accept the facts. Not only the Republicans, but we had three Southern Democrats from very pro-Nixon districts on the committee, maybe even more pro-Nixon than some of the Republican districts, so there was a lot of persuading to do.

I think the issue of fairness and also competence was critical. And Rodino didn’t go around saying, “I think the president should be impeached.” The demeanor was appropriate to the solemnity and gravity of the circumstance, and I think members of Congress should bear that in mind. This is an extremely serious and grave action — the impeachment of a president — because it undoes an election, which is the centerpiece of our democracy. The framers made it hard for that reason. They didn’t want it to be done lightly or frivolously, and so the demeanor with which it’s carried out is also important.

REUM: In the rush to supposedly expedite this whole thing, you’re losing a lot of the procedural safeguards and fairness aspects of the process that are pretty critical. And, in fact, part of the reason why our inquiry, I think, was very successful and praised pretty much in all quarters afterward was that we were very heavily insulated from the Congress [members] on the committee. Fortunately, both [House Judiciary Committee chief counsel John] Doar and [chief Republican counsel Albert] Jenner had the kind of independent status and reputations for integrity that they could resist those pressures, but I don’t get so much that feeling at this point. Given the gravity of this, you really need to have a vote of the full House. This is something that’s a real serious undertaking. You can’t do this by press conference. There may be a political purpose for trying to do this fast, but it ultimately undermines giving it a nonpartisan feel as well as procedurally trying to do it in the most fair way.

Interviews have been edited for clarity and condensed for length.