Kanchi Gandhi is an expert on scientific plant names and serves as the gatekeeper for naming new species, and reconsidering names of old ones, one of the hidden operations of science.

Photos by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographeri

A rose by any other name — could be confusing

Kanchi Gandhi is part of a select posse of experts, armed with the accepted rules, who ride herd on the nomenclature of the world’s plants

Scientists count 1.4 million different names for plants on Earth. But botanists estimate there are just 300,000 existing species. That means there’s a veritable Tower of Babel of plant names are kicking around.

So what happened?

In some cases it was a matter of scientists “discovering” slightly different variants of the same species; in others it was owing to new descriptions of wide-ranging species in geographically diverse locations; then there have been changes in scientific understanding of relationships between species; and finally, there’s plain old human error.

Kanchi Gandhi to the rescue.

The senior nomenclatural registrar is part of a small community of global experts toiling in relative obscurity to bring order from the chaos and ensure that when botanists talk to each other about a plant, they can be confident they’re talking about the same one.

“I think Kanchi is really outstanding in being one of the few nomenclaturists left in the world who understands — and referees — the ‘rules’ when it comes to naming new species of plants,” said Michael Dosmann, keeper of the living collections at Arnold Arboretum. “It really is a labor of love and often is too in-the-weeds or bureaucratic for a majority of botanists to get as proficient as Kanchi is.”

The job, Dosmann said, includes not only ensuring that newly discovered plants are named properly, but also serving as something of a global taxonomic cop tossing out names that don’t follow guidelines, sending botanists flush with the excitement of new discovery back to the keyboard for another try.

In fairness to those with naming “fails” to their credit, the rules that have sprung up since Carl Linnaeus’ “Species Plantarum” in the mid-18th century first described a plant using two Latin names are complex. Gandhi keeps in his Harvard Herbarium office the 203-page “International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants” — known as “The Shenzhen Code” for the city where this latest version of guidelines was adopted in 2018.

“I like what I do, sharing knowledge. It’s not a high-profile job, but I live simply.”

Kanchi Gandhi

Two hundred and three pages may seem an excessive number of rules — they deal largely with technical things like, say, the proper way to convert an individual’s name into a Latin or Greek scientific one (discoverers often name new species after themselves, loved ones, or mentors). Gandhi notes, however, that the principles not only keep everyone on the same page regardless of native language or culture, but also result in names that are more than mere monikers. They provide information such as other plant relatives of a species and, in some instances, can note where it was found, the name and gender of the discoverer, or a striking characteristic.

Before Linnaeus established his system, plants were known by what are called polynomials: long names made up of multiple descriptive terms. Before “Species Plantarum” was published, just 5,000 plants were described, Gandhi said, and talented botanists memorized them all.

Linnaeus’ innovation, first applied to plants and later to animals, was to create a two-part name, today given in either Latin or Greek. The first designates the broader group to which the plant belongs, called a genus, and the second names the plant itself as a species.

Over the centuries since, scientists have created more than a million additional names, creating enough confusion that international collaborations of scientists arose to police the situation and write the first naming guidelines — the ancestor of today’s Shenzhen Code — more than a century ago, Gandhi said.

Today, nomenclature is regulated by the International Association for Plant Taxonomy, based in Bratislava, Slovakia, on whose Committee for Vascular Plants Gandhi sits. The committee works to ensure scientists everywhere use the same standards. It also wrestles with knotty issues such as renaming plants. One recent drama involved three Chinese botanists proposing to change the scientific name of the apple tree from Malus pumila to Malus domestica. Malus pumila was the older name and otherwise met naming guidelines, so Gandhi voted against the change, a sentiment that initially carried the day. The proposers didn’t give up, however, and on their second try, narrowly succeeded — against Gandhi’s vote.

“M. pumila had priority and was widely used,” Gandhi said. “They [committee members] wanted the problem to go away. I was unhappy, but you have to go with the majority.”

Gandhi got his start in plant nomenclature on the job. He grew up in India and got a master’s degree in botany from Bangalore University in 1970. He was steered to collecting, classification, and nomenclature in his first job, surveying rainforest plants in his home state of Karnataka for a collaborative project between Indian scientists and the Smithsonian Institution. Gandhi said Dan Nicolson, the Smithsonian’s project director, became a mentor and taught him the basics of plant nomenclature.

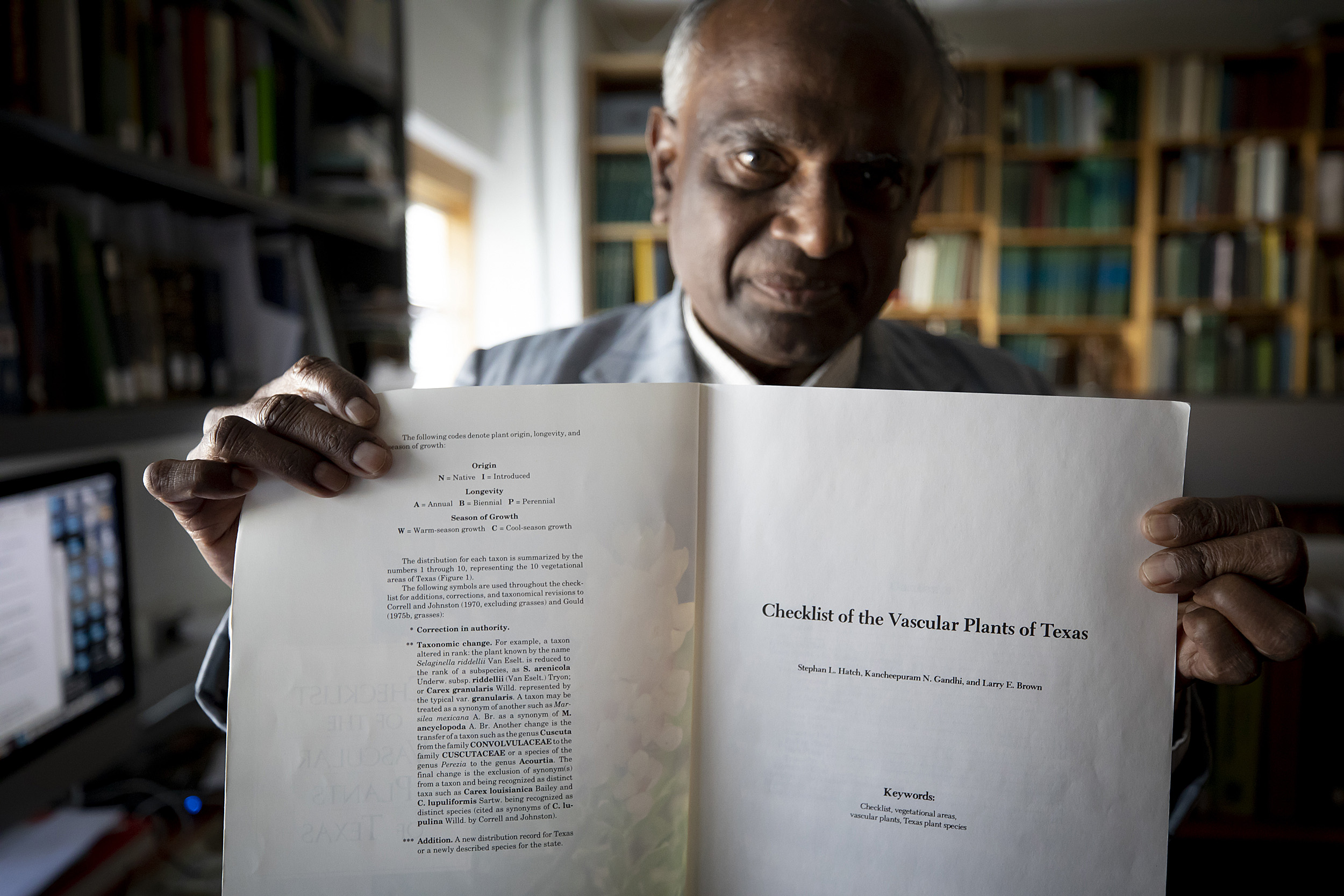

Gandhi threw himself into the work and, when the project concluded four years later, was a junior scientific assistant and responsible for roughly one-third of the resulting book. He went on to teach at Bangalore University for eight years and then headed to the U.S. in the 1980s for a doctorate, receiving a Ph.D. from Texas A&M. There, he co-authored the “Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Texas,” which landed him a job at the University of North Carolina. That’s where Harvard’s David Boufford found him on a search to fill an opening for a Herbarium nomenclaturist. Gandhi has been at Harvard since 1995.

Boufford, a senior research scientist, said filling the post was crucial because Harvard for decades had kept the botanical community up to date on the latest plant discoveries — and their names — through its Gray Herbarium Index. The index was distributed through printed index cards mailed to libraries, herbaria, and other subscribers. By the mid-1990s, efforts were being made to digitize the index, which further expanded its reach, including subscribers in Latin America for the first time. Since then, the work has been taken up by the International Plant Names Index, a collaboration between the Harvard Herbarium, the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and the Australian National Herbarium.

Gandhi, now 71, still arrives at 9 each morning and works until 9 in the evening, when he hops the Red Line to Alewife and catches the last bus to Lexington at 9:35 p.m. He routinely works weekends and credits his wife, Kasthuri, for picking up the slack at home. Despite the pace, he has no plans to slow down and said he’ll continue working as long as the department will have him.

“I like what I do, sharing knowledge,” Gandhi said. “It’s not a high-profile job, but I live simply.”

Today, among his duties, Gandhi is the nomenclature and etymology editor for the massive, 30-volume “Flora of North America” whose first volume was published in 1993 and which Gandhi said he hopes will finally be finished in the next couple of years. He’s also editor of the International Plant Names Index and associate editor of the journal Rhodora. He daily fields queries from scientists wrestling with knotty name issues and counts among his credits straightening out the name of the California holly for which Hollywood is likely named — he notes jokingly that movie producers have never credited his work saving “Hollywood.”

Mamiyil Sabu, a professor of botany at the University of Calicut in India, said although expert nomenclaturists are indeed rare, what really sets Gandhi apart is his willingness to help. He’s aided Sabu with naming problems on several occasions and repeatedly traveled to India to lecture on the topic.

“He’s very simple, very humble. He’s ready to help everybody,” Sabu said.

For that work, he’s been named an honorary member of the Indian Association for Angiosperm Taxonomy and in 2010, received a distinguished service award from the American Association of Plant Taxonomists.

Perhaps most enduring, however, is the decision by several botanists to name plants after him — meticulously following international naming rules, of course. Earlier this year, Sabu became the eighth and latest to do so, naming a new species of ginger Globba kanchigandhii.