iStock

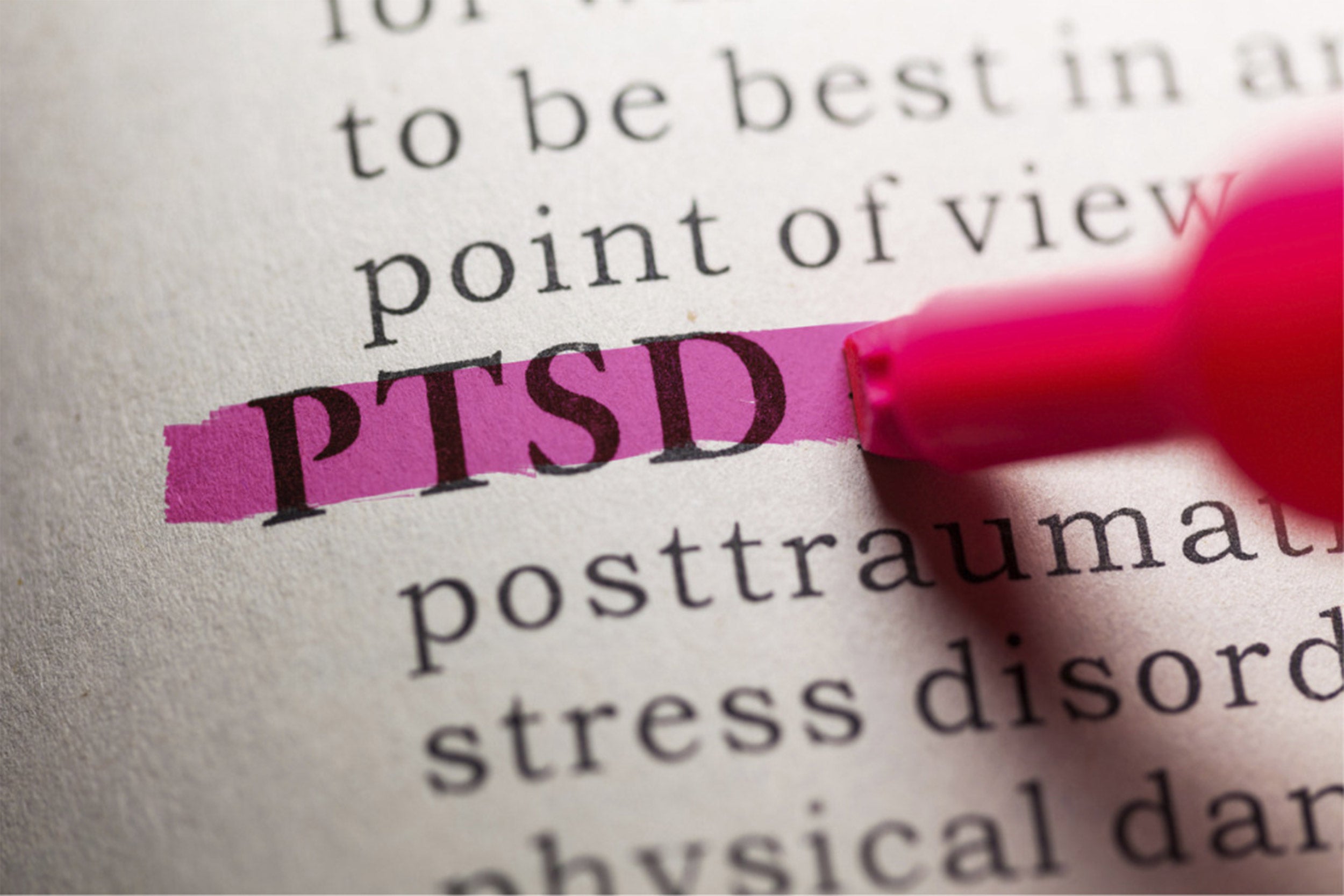

PTSD linked to increased risk of ovarian cancer

Trauma associated with the most aggressive types of ovarian cancers, even decades later

Women who experienced six or more symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at some point in life had a twofold greater risk of developing ovarian cancer compared with women who never had any PTSD symptoms, according to a new study from researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Moffitt Cancer Center.

The findings indicate that having higher levels of PTSD symptoms, such as being easily startled by ordinary noises or avoiding reminders of the traumatic experience, can be associated with increased risks of ovarian cancer even decades after women experience a traumatic event. The study also found that the link between PTSD and ovarian cancer remained for the most aggressive forms of ovarian cancer.

The findings were published today in Cancer Research.

“In light of these findings, we need to understand whether successful treatment of PTSD would reduce this risk, and whether other types of stress are also risk factors for ovarian cancer,” said co-author Andrea Roberts, research scientist at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest gynecologic cancer and the fifth-most-common cause of cancer-related death among U.S. women. Studies in animal models have shown that stress and stress hormones can accelerate ovarian tumor growth, and that chronic stress can result in larger and more invasive tumors. A prior study found an association between PTSD and ovarian cancer in humans, but the study included only seven women with ovarian cancer and PTSD.

“Ovarian cancer has been called a ‘silent killer’ because it is difficult to detect in its early stages; therefore identifying more specifically who may be at increased risk for developing the disease is important for prevention or earlier treatment,” said co-author Laura Kubzansky, Lee Kum Kee Professor of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Harvard Chan School.

To better understand how PTSD may influence ovarian cancer risk, researchers analyzed data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, which tracked the health of tens of thousands of women between 1989 and 2015 through biennial questionnaires and medical records. Participants were asked about ovarian cancer diagnosis on each questionnaire, and information was validated through a review of medical records.

In 2008, 54,763 Nurses’ Health Study II participants responded to a supplemental questionnaire focused on lifetime traumatic events and symptoms associated with those events. Women were asked to identify the event they considered the most stressful, and the year of this event. They were also asked about seven PTSD symptoms they may have experienced related to the most stressful event.

Based on the responses, women were divided into six groups: no trauma exposure; trauma and no PTSD symptoms; trauma and one to three symptoms; trauma and four or five symptoms; trauma and six or seven symptoms; and trauma, but PTSD symptoms unknown.

After adjusting for various factors associated with ovarian cancer, including oral contraceptive use and smoking, the researchers found that women who experienced six or seven symptoms associated with PTSD were at a significantly higher risk for ovarian cancer than women who had never been exposed to trauma. Women with trauma and four or five symptoms were also at an elevated risk, but the risk did not reach statistical significance.

The study also showed that women who experienced six or seven symptoms associated with PTSD were at a significantly higher risk of developing the high-grade serous histotype of ovarian cancer — the most common and most aggressive form of the disease.

“Ovarian cancer has relatively few known risk factors — PTSD and other forms of distress, like depression, may represent a novel direction in ovarian cancer prevention research,” said Shelley Tworoger, associate center director of population science at Moffitt. “If confirmed in other populations, this could be one factor that doctors could consider when determining if a woman is at high risk of ovarian cancer in the future.”

Other Harvard Chan School researchers who contributed to the study included Karestan Koenen and Yongjoo Kim. Tianyi Huang of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School was also a co-author.

Funding for this study came from DOD grant W81XWH-17-1-0153.