Wyss Institute at Harvard University

A gentle grip on gelatinous creatures

Ultra-soft underwater grippers use fettuccini-like fingers to catch and release jellyfish without harm

Jellyfish are about 95 percent water, making them some of the most diaphanous, delicate animals on the planet. But their remaining 5 percent has yielded important scientific discoveries, such as green fluorescent protein that scientists now use extensively to study gene expression, and life-cycle reversal that could hold the keys to combating aging.

Jellyfish may very well harbor other, potentially life-changing secrets, but the difficulty of collecting them has severely limited the study of these “forgotten fauna.” The sampling tools available to marine biologists on remotely operated vehicles were largely developed for the marine oil and gas industries, and are far better-suited to grasping and manipulating rocks and heavy equipment than jellies, which they often shred to pieces while trying to capture them.

Now, a new technology developed by researchers at Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), and Baruch College at City University of New York offers a novel solution to that problem in the form of an ultra-soft, underwater gripper that uses hydraulic pressure to gently but firmly wrap its fettuccini-like fingers around a single jellyfish, then release it without causing harm. The gripper is described in a new paper published in Science Robotics.

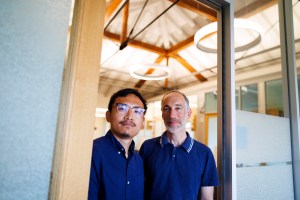

“Our ultra-gentle gripper is a clear improvement over existing deep-sea sampling devices for jellies and other soft-bodied creatures that are otherwise nearly impossible to collect intact,” said first author Nina Sinatra, a former graduate student in the lab of Robert Wood at the Wyss Institute. “This technology can also be extended to improve underwater analysis techniques and allow extensive study of the ecological and genetic features of marine organisms without taking them out of the water.”

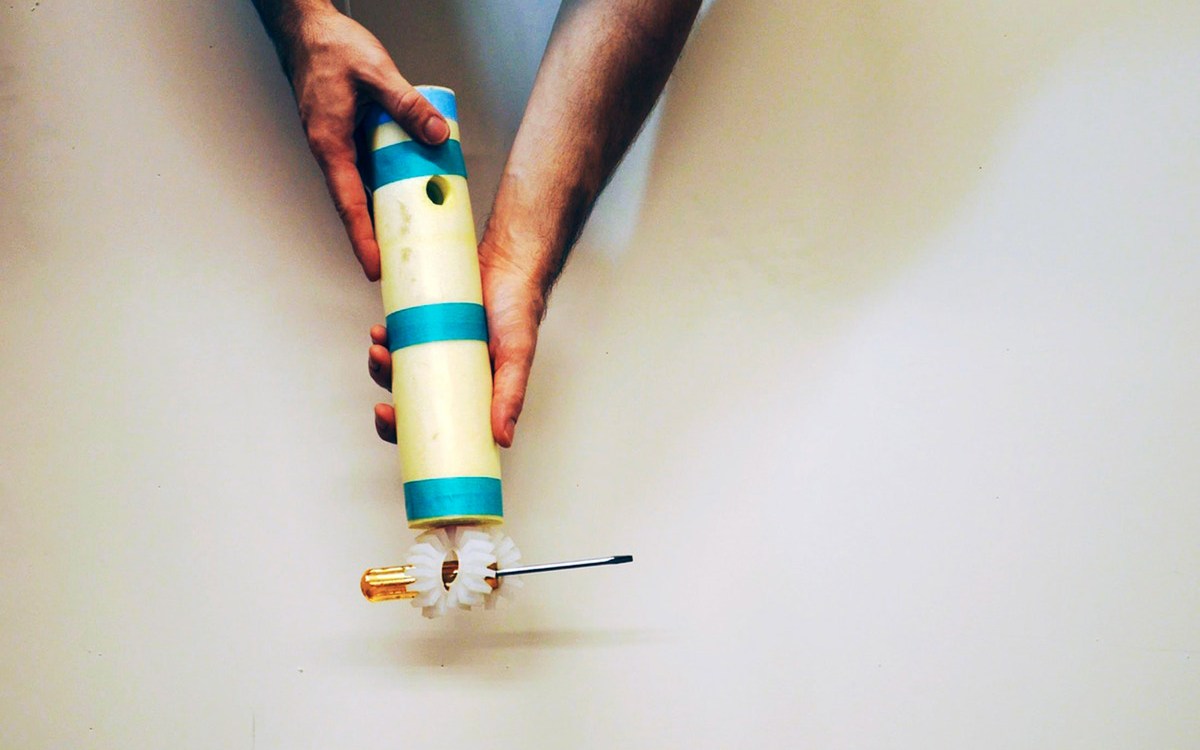

The gripper’s six “fingers” are composed of thin, flat strips of silicone with a hollow channel inside bonded to a layer of flexible but stiffer polymer nanofibers. The fingers are attached to a rectangular, 3D-printed plastic “palm” and, when their channels are filled with water, curl in the direction of the nanofiber-coated side. Each finger exerts an extremely low amount of pressure — about 0.0455 kPA, or less than one-tenth of the pressure of a human’s eyelid on their eye. By contrast, current state-of-the-art soft marine grippers, which are used to capture delicate but more robust animals than jellyfish, exert about 1 kPA.

The researchers fitted their ultra-gentle gripper to a specially created, hand-held device and tested its ability to grasp an artificial silicone jellyfish in a tank of water to determine the positioning and precision as well as the optimum angle and speed at which to capture a jellyfish. They then moved on to the real thing at the New England Aquarium, where they used the grippers to grab swimming moon jellies, jelly blubbers, and spotted jellies, all about the size of a golf ball.

The gripper was successfully able to trap each jellyfish against the palm of the device, and the jellyfish were unable to break free from the fingers’ grasp until the gripper was depressurized. The jellyfish showed no signs of stress or other adverse effects after being released, and the fingers were able to open and close roughly 100 times before showing signs of wear and tear.

“Marine biologists have been waiting a long time for a tool that replicates the gentleness of human hands in interacting with delicate animals like jellyfish from inaccessible environments,” said co-author David Gruber, a 2017-2018 Radcliffe Fellow, professor of biology and environmental science at Baruch College, and a National Geographic Explorer. “This gripper is part of an ever-growing soft robotic toolbox that promises to make underwater species collection easier and safer, which would greatly improve the pace and quality of research on animals that have been under-studied for hundreds of years, giving us a more complete picture of the complex ecosystems that make up our oceans.”

The ultra-soft gripper is the latest innovation in soft robotics for underwater sampling, an ongoing collaboration between Gruber and Wood that has produced the origami-inspired RAD sampler and multifunctional “squishy fingers” to collect a diverse array of hard-to-capture organisms, including squids, octopuses, sponges, sea whips, corals, and more.

“Soft robotics is an ideal solution to long-standing problems like this one across a wide variety of fields, because it combines the programmability and robustness of traditional robots with unprecedented gentleness thanks to the flexible materials used,” said Wood, a Wyss core faculty member, co-lead of the Wyss Institute’s Bioinspired Soft Robotics Platform, the Charles River Professor of Engineering and Applied Sciences at SEAS, and a National Geographic Explorer.

The team is continuing to refine the ultra-soft gripper’s design, and aims to conduct studies that evaluate the jellyfishes’ physiological response to being held by the gripper, to more definitively prove that it does not cause the animals stress. Wood and Gruber, who are also co-principal investigators of the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s Designing the Future project, will further test their various underwater robots on an expedition aboard the research ship Falkorin 2020.

“At the Wyss Institute we are always asking, ‘How can we make this better?’ I am extremely impressed by the ingenuity and out-of-the-box thinking that Rob Wood and his team have applied to solve a real-world problem that exists in the open ocean, rather than in the laboratory. This could help to greatly advance ocean science,” said Wyss Institute Founding Director Donald Ingber, who is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital, and professor of bioengineering at SEAS.

Additional authors of the paper are Clark Teeple, Daniel Vogt, and Kevin Kit Parker from the Wyss Institute and Harvard SEAS. Parker is a core faculty member of the Wyss Institute and the Tarr Family Professor of Bioengineering and Applied Physics at SEAS.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Harvard University Materials Research Science and Engineering Center, the National Academies Keck Futures Initiative, and the National Geographic Society.