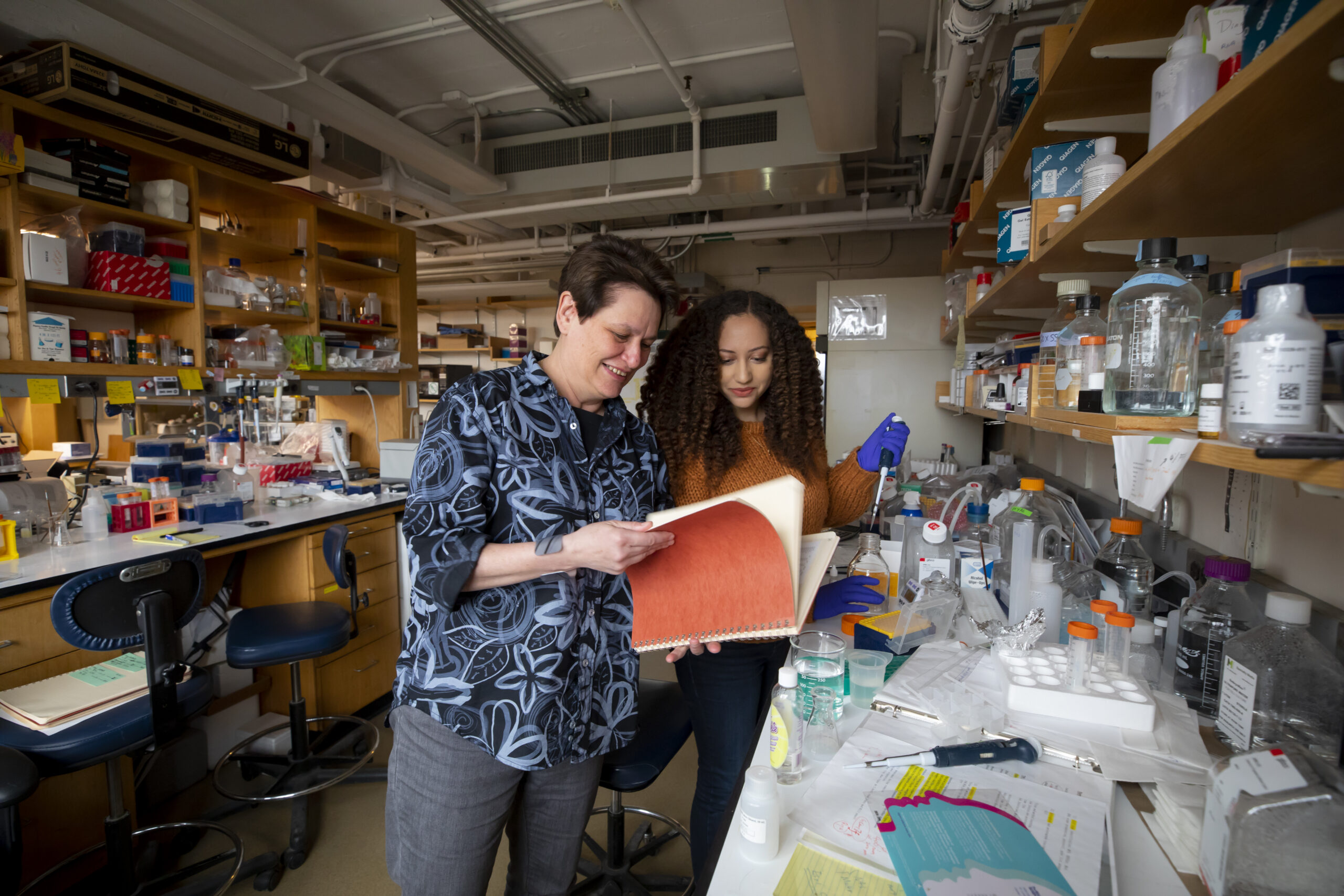

Catherine Dulac (left) received additional financial support from a faculty appointment. With the funding, she created a fellowship to support undergraduate research. The first recipient is Melonie Vaughn (right).

Photos by Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Giving to the next generation

Catherine Dulac uses money from her endowed professorship on a fellowship for neuroscience undergrad

When Catherine Dulac was named the Lee and Ezpeleta Professor of Arts and Sciences last year, she wanted to make a difference. She had learned that donors Kewsong Lee ’86, M.B.A. ’90, and Zita Ezpeleta ’88, J.D. ’91, had created the endowed position, which lasts for five years and comes with a monetary award, because Harvard had changed their lives.

“I thought, what is it we do that makes a difference?” Dulac recalled asking herself, during a conversation in her office in the BioLabs.

The answer, she realized, was to use the award not to fund her lab, but to create a fellowship for a deserving undergraduate and pay the experience forward.

The timing was perfect for then-rising junior Melonie Vaughn ’19. That summer, the neuroscience concentrator had received a Weissman International Internship, which had made it possible for her to do neurobiological and psychopharmacological research at the Universidad Miguel Hernandez de Elche in Alicante, Spain. The experience was transformative. “I knew after the short time I spent working in a lab that it was something really exciting for me and possibly what I wanted to do with my career,” said Vaughn, who came to Harvard from Lathrop, Calif.

Dulac understood.

“There’s something you learn when you’re actually experiencing research that is more powerful than just reading it out of a book or listening in lecture,” she said.

Because she had taught Vaughn, Dulac — the Higgins Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator whose lab uses molecular, genetic, and optical techniques to explore the molecular and neuronal basis of innate social behaviors in the mouse — was already aware of the undergrad’s interest and promise. The challenge for Vaughn was finding the time required to continue her research.

“When I first started working in Dulac’s lab, I was working two jobs on campus,” said Vaughn, who is financially independent from her parents. The daughter of a single mother with a chronic health condition, she has not only supported herself, but has sent money home to help her family by working as an assistant building manager and at Cambridge Queen’s Head pub, among other part-time positions. “I was working maybe 25 hours a week at one point on top of trying to go to classes, and I was having difficulty managing,” recalled Vaughn, who was supported by Harvard’s Financial Aid Initiative. “It was becoming increasingly hard for me to put hours into the lab, especially working with mice, where experiment hours were really, really long.”

Knowing the time and attention that research required, Dulac believed such dedication ought to be compensated. Giving Vaughn the fledgling fellowship was a way of “enabling somebody who has the eagerness to do research to have this as what she does to get an income,” said Dulac.

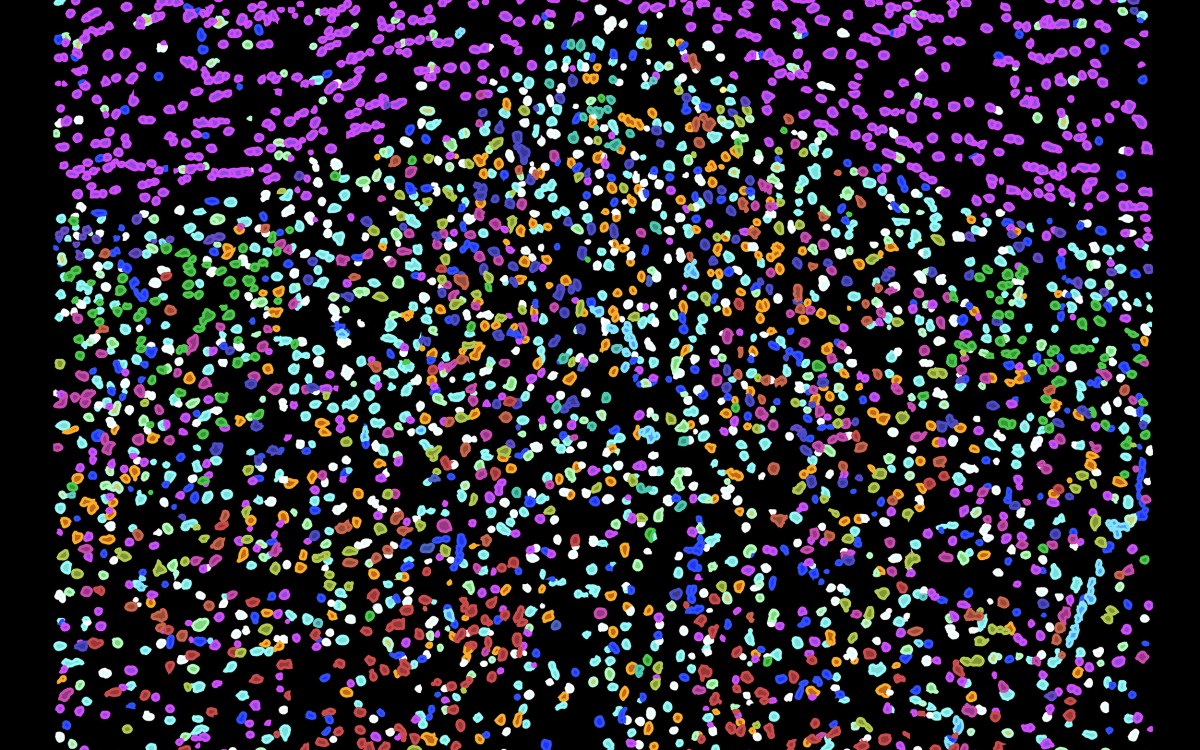

Vaughn’s project grew naturally out of the molecular and cellular biology focus of Dulac’s lab as well as her personal experience. “My brother has an autism diagnosis,” she said, “and I’m interested in studying neurodevelopmental disorders.” In particular, she focused on a phenomenon called “the fever effect,” in which various symptoms associated with autism — such as language deficits and self-harming repetitive behaviors — are lessened while the subject has a fever. They reassert themselves when the fever is gone.

“We wanted to see if we could replicate this phenomenon in a model organism,” Vaughn said. Under the supervision of Dulac and postdoctoral fellow Jessica Osterhout, she designed a series of experiments that involved injecting mice with bacterial liposaccharides, “basically to give them fever in the same way a bacterial infection would,” she explained, and then seeing if their behaviors changed and how long the effects lasted.

Vaughn’s contributions will eventually become part of published research, said Dulac. Although the work is not finished, it is on its way. “We have some very promising leads that were developed by Melonie,” said Dulac. “What Melonie has done is really significant.”

Being able to spend time on research, said Vaughn, ultimately made it possible for her to write a thesis. It may also have launched her into a career. “This fall, I’ll be starting at UC San Diego to get a Ph.D. in neuroscience,” said the graduating senior. “I’m really excited about that, but honestly without this fellowship I can’t see a way that I would’ve been able to continue to do the quality and the level of work that I really wanted to be able to do. That really opened that door for me.”

But Dulac said she got much more from Vaughn through the experience.

“This is the role of a teaching scientist,” said Dulac. “Science and research are people working together to exchange ideas. It’s a human community.”