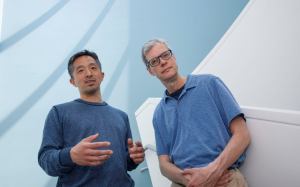

OEB Professor Andrew Berry and his students are studying different facets of evolution.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Written in the bones

Doctoral students describe projects at the cutting edge of evolutionary inquiry

Might it be the humble pelvis that makes us human, and not the brain? Do butterfly hybrids mean evolutionary trees should look more like networks? What can deer mice teach us about genetics and inheritance? And what’s up with all the human bones at Roopkund Lake?

A quartet of Harvard doctoral students gave a glimpse of the future of evolutionary inquiry Thursday evening, describing the cutting-edge tools they’ve become adept at wielding to investigate conundrums that get to the heart of some of the most fundamental questions of our time: how we became human, what happened in our past, and how animals slowly become different.

The event, “Frontiers in Evolution,” drew about 100 people to the Geological Lecture Hall in Harvard’s Geological Museum building. Part of the Harvard Museum of Natural History’s “Evolution Matters” lecture series, the event was moderated by lecturer on organismic and evolutionary biology (OEB) Andrew Berry. It featured talks on varied topics by doctoral students in OEB and genetics Nate Edelman, Emily Hager, Éadaoin Harney, and Mariel Young.

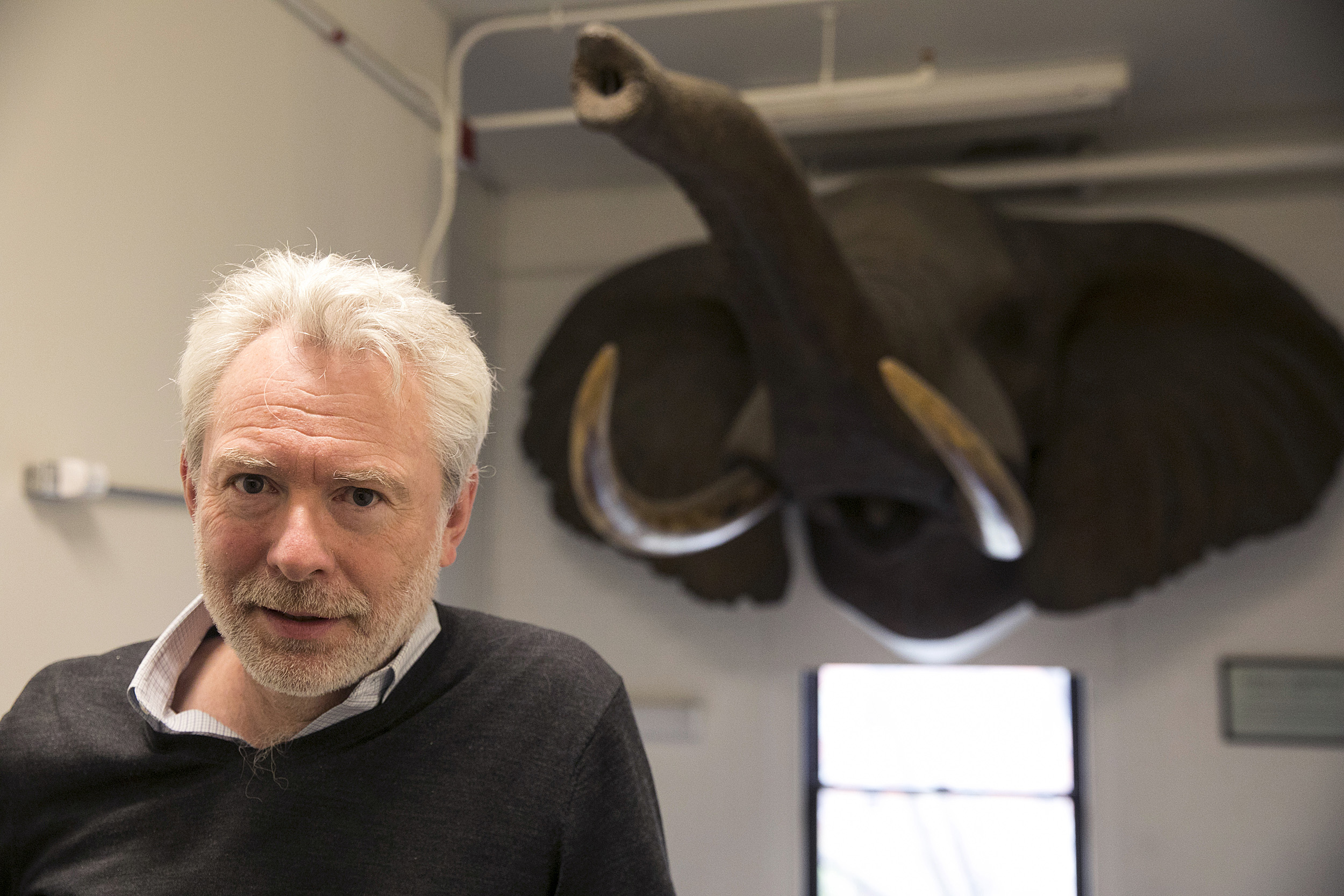

Berry praised the museum for regularly hosting speakers who have made significant and thought-provoking contributions to their fields, but said that they are often senior faculty members and experienced researchers. By the time they’ve reached that stage, he said, much of their time is spent directing younger scientists, securing funding for the lab, and doing relatively little actual science.

“They’re not the ones doing the science — they are sitting in their offices writing grants, or probably jetting around the world giving keynote addresses,” Berry said. “The actual science — and this is perhaps science’s best-kept secret — is being done by graduate students. They’re the ones actually engaged with the scientific process. They’re the ones developing new tools. They’re the ones, if you like, hacking away at the rock face of knowledge.”

The evening’s event, he said, was dedicated to hearing from those still getting their hands dirty. Each student gave a brief presentation on his or her work and then took questions from the audience.

The walking-pelvis primate

Young, a doctoral student in the human evolutionary biology lab of Terence Capellini, Richard B. Wolf Associate Professor, calls the pelvis the most important “evolutionary bone” in the human body. Young, whose work examines the evolution of the pelvis, professes “an almost unhealthy obsession” with it.

That obsession is rooted in the fact that when you look at skeletons of humans and their closest animal relative, the chimpanzee, the differences in their pelvises stand out. The chimp’s is elongated and flattened, an illustration of the different ways the two species make a living — the chimp in trees and on all fours on the ground, and the human upright and walking on two feet. The broad sides of the human pelvis are designed to anchor the muscles needed for walking, while its basketlike appearance supports our guts as we stride around the countryside.

Young is using genetic analysis to understand how species that are so closely related can have pelvises that looks so different. The answer, she said, lies not in the DNA itself, but in the regulatory switches that determine which genes are turned on and off.

A key to the pelvis’ importance, she said, is that 3 million years ago, about halfway back to our most recent common ancestor with chimps, the famous chimplike human “Lucy” (Australopithecus afarensis) already had a pelvis a lot like modern humans but her brain was still chimplike. It was our pelvis, Young said, that first differentiated us and enabled our ancestors to better move across the landscape and secure the resources needed to develop our energy-greedy brains.

“I would argue that what makes us human is not necessarily our big impressive brain,” Young said, “but our pelvis itself.”

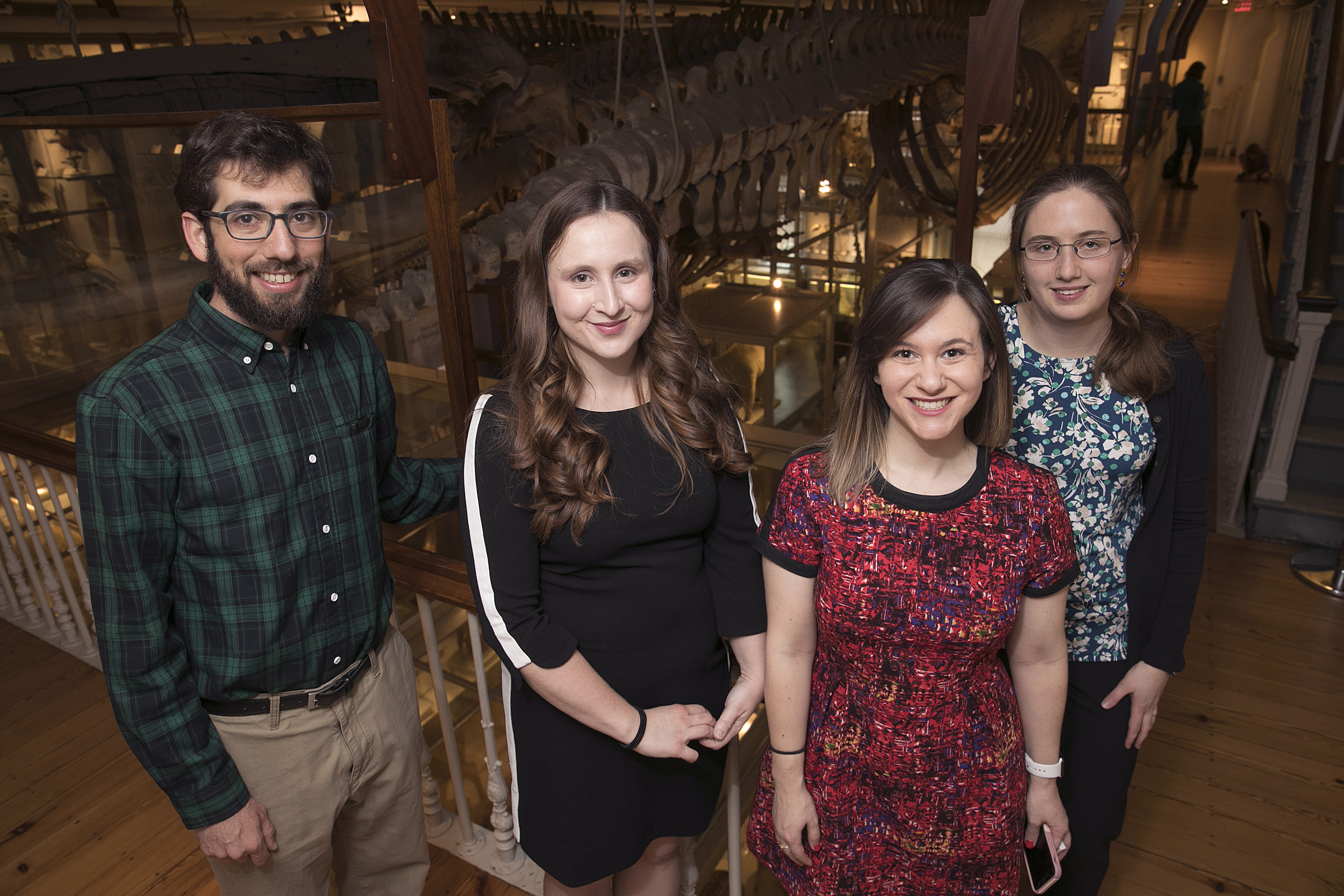

Graduate students Nate Edelman (left), Éadaoin Harney, Mariel Young, and Emily Hager at the Harvard Museum of Natural History.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

An evolutionary tree from butterfly hybrids

Edelman, a doctoral student in Professor in Residence James Mallet’s lab, is using genetic analysis to examine the relationships between six species of Heliconius butterflies, a group of species common to Central and South America.

Known as longwing butterflies, there are 47 different species with overlapping ranges. They’re known to hybridize frequently, but though hybrids are often considered sterile, like mules, the hybrid butterflies can be fertile.

Edelman’s research examined the six selected species’ history using genetic analysis. After sequencing their genomes, he found that hybridization was a common and recurring event. That means the typical evolutionary tree might have not just individual branches, but crossbars between the branches where mixing through hybridization occurs.

And it’s not just butterflies that hybridize, Edelman said. As we sequence more and more organisms’ genomes, it is becoming apparent that hybridization is far more common than we thought. Even humans, he pointed out, hybridized with Neanderthals at one point.

“In fact hybrids are everywhere,” Edelman said. “Hybridization is something we need to take account of very seriously when we think about our evolutionary history.”

Tails, trees and what the deer mouse taught us

Hager, a doctoral student in Professor Hopi Hoekstra’s lab, is examining the differences between two populations of deer mice — those that live on the prairie and those that live in the forest. Though they’re the same species, the different populations live very different lifestyles, so Hager wants to probe their genetic roots.

The forest mice like to climb and are good at it. They have longer tails and larger feet. But since they are the same species, Hager’s investigation started by ruling out experience as an explanation for their differing skills. She did that by raising the mice together in the lab, away from the forest’s vertical terrain. Nonetheless the forest mice performed much better at a balancing test the first time they tried it, a hint at the genetic roots of their differing climbing ability.

One by one, Hager found that there were separate genes for long tails, large feet, and the desire to climb — a genetic trait not necessarily connected to the ability to climb. As she crossbred mice, the result was some with the ability to climb but not the interest, and, more poignantly, some who kept trying and falling off.

Solving the mystery of skeleton lake

Harney, a doctoral student in the labs of Harvard Medical School Professor David Reich and Professor John Wakeley, is using the rapidly developing field of ancient DNA analysis to solve the ancient mystery of Roopkund Lake.

The lake sits at 16,000 feet, high in the Indian Himalayas. The site, with no settlements nearby, holds hundreds of human skeletons, visible during the warmer months when the ice thaws. Local lore said they belonged to pilgrims who angered a goddess who rained death on them, and scientists held that it was a large group of people, perhaps an army troop, who got caught in some kind of catastrophe.

Harney put the new tools of ancient DNA analysis to work. Working in collaboration with Indian archaeologists, she got samples from 38 individuals and extracted DNA from the old bones.

The analysis showed a large group, dating back to the ninth century, came from across India, likely because the site was near a pilgrimage route that regularly brought people into the region. A second group, dated to the early 1800s, had genetic history from the eastern Mediterranean, centered on the island of Cyprus, while a third origin, from around the same date, consisted of a lone individual with Southeast Asian roots.

“So by combining biomolecular analyses with ancient DNA and carbon dating we found the skeletons of Roopkund Lake are not the product of a single catastrophic event as previously thought, but instead is the result of multiple distinct diverse groups of people making separate journeys to Roopkund Lake, only to die,” Harney said. “We turn now to archaeologists and historians to help us fill in the gaps.”