Stitching together the stars

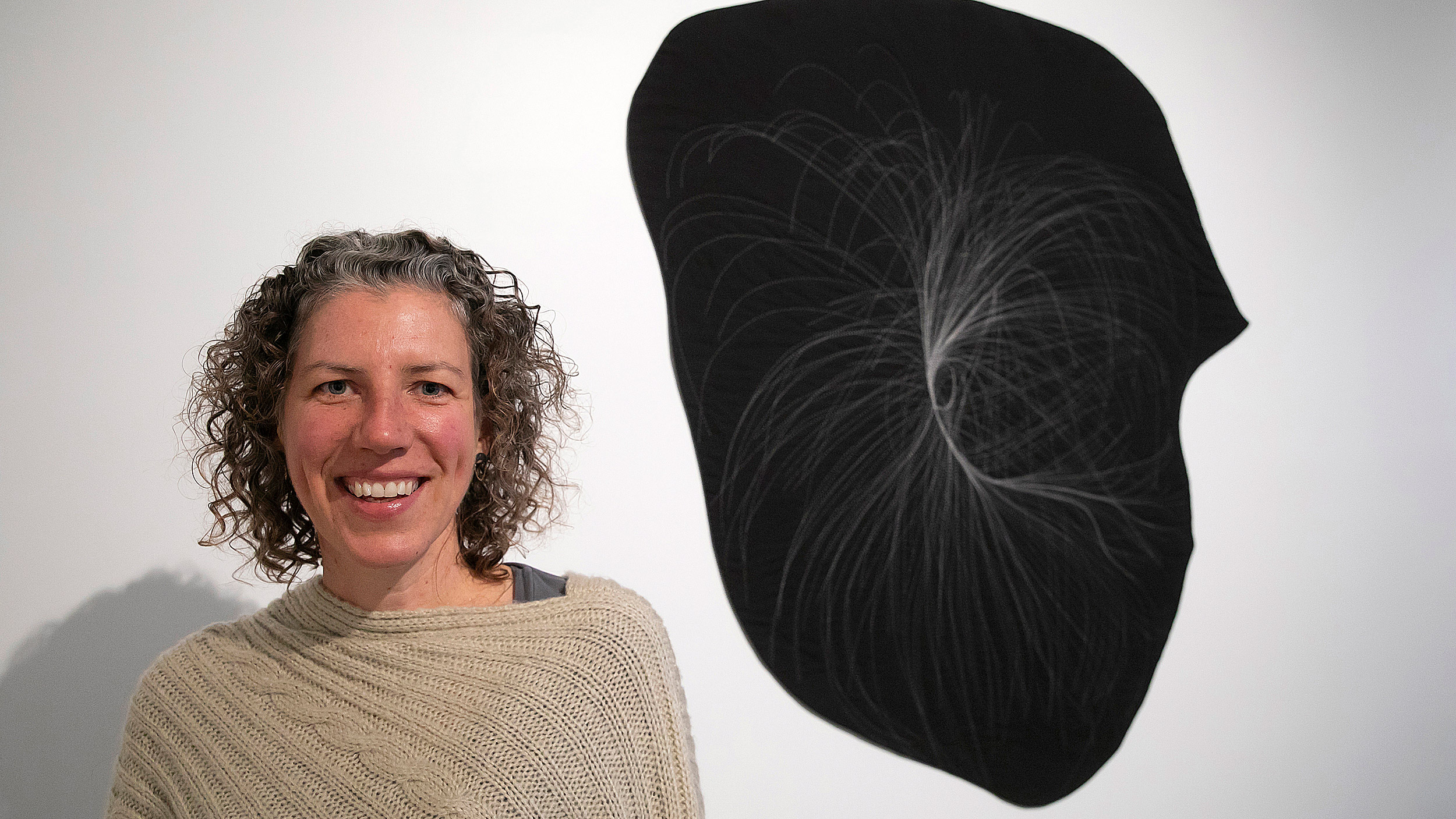

Anna Von Mertens’ cosmic quilts are on view at Byerly Hall through Jan. 19.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

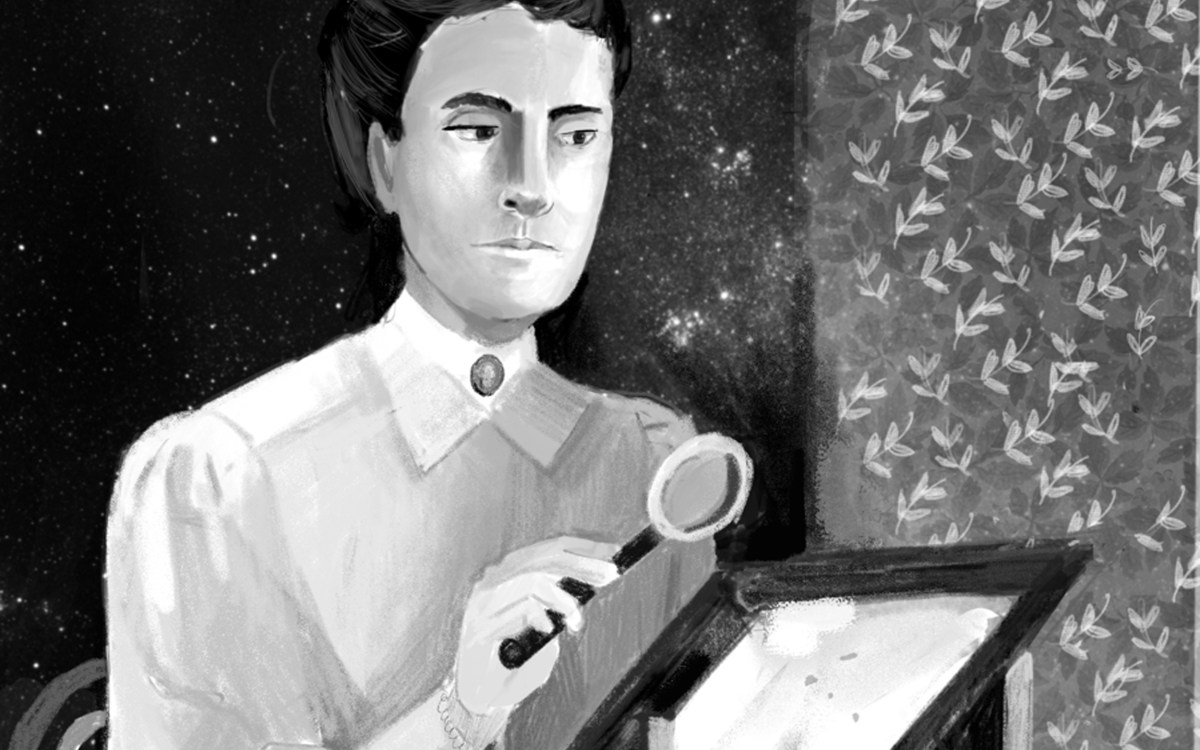

Radcliffe quilting exhibit honors astronomer Henrietta Leavitt, whose pioneering work helped unlock the universe

Her countless hours at Harvard mapping the stars are central to understanding the universe. Though she didn’t live to see the far-reaching implications of her work, a new Radcliffe exhibit shows how her efforts helped unlock mysteries of the cosmos.

Radcliffe graduate Henrietta Leavitt was one of the more than 80 women who worked at the Harvard Observatory from the late 1800s to the mid-1900s carefully analyzing a record of the heavens on glass-plate negatives, a collection that includes more than 500,000 celestial moments and is considered the oldest and most comprehensive archive of the night sky.

But Leavitt died in 1921, before others used her observations of Cepheid variable stars (those whose brightness pulses at regular intervals), and her key discovery of the relationship between a Cepheid star’s luminosity and how frequently it pulses, to make a range of key discoveries about our galaxy. Her work enabled other astronomers to measure the distance to the stars and determine the shape of the Milky Way. American astronomer Edwin Powell Hubble built on her findings, proving the existence of galaxies beyond our own and showing that the universe was expanding.

Leavitt’s research became the first rung “on the distance ladder to the stars,” said artist Anna Von Mertens, whose needle and thread honors the “Harvard Computer’s” life and work in the show “Measure,” on view at Byerly Hall through Jan. 19.

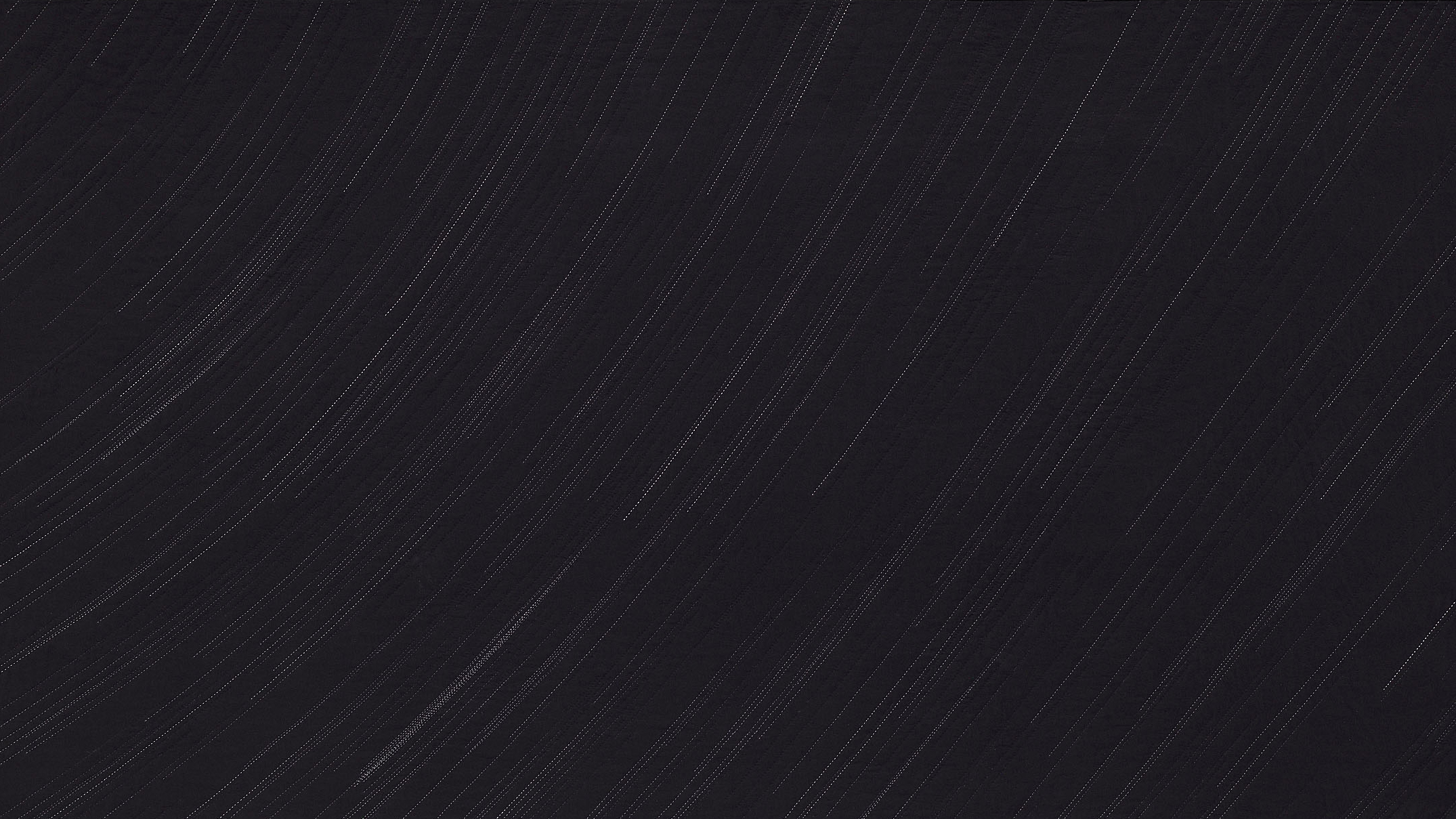

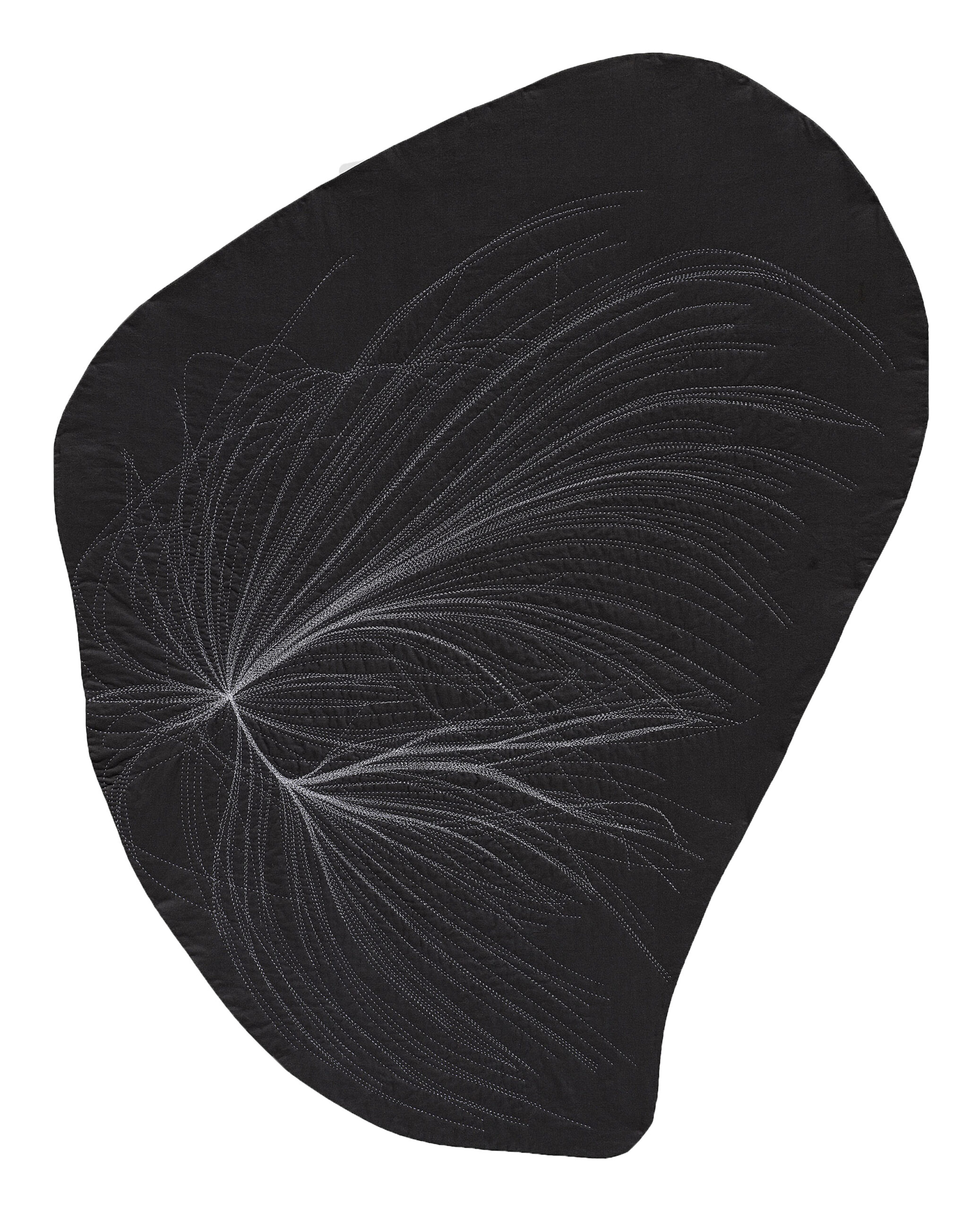

In a diptych on the walls of the Johnson-Kulukundis Family Gallery, Von Mertens’ series of meticulous white and gray hand-sewn stitches on a black background — mapped out with help from star calculation software — depict the stars fading from the skies above Lancaster, Pa., on the morning Leavitt was born, July 4, 1868, and the stars returning to view over Cambridge, Mass., on the day she died, Dec. 12, 1921.

Stitches depict the stars fading from view on the morning of Leavitt’s birth.

Courtesy of artist Anna Von Mertens and Elizabeth Leach Gallery

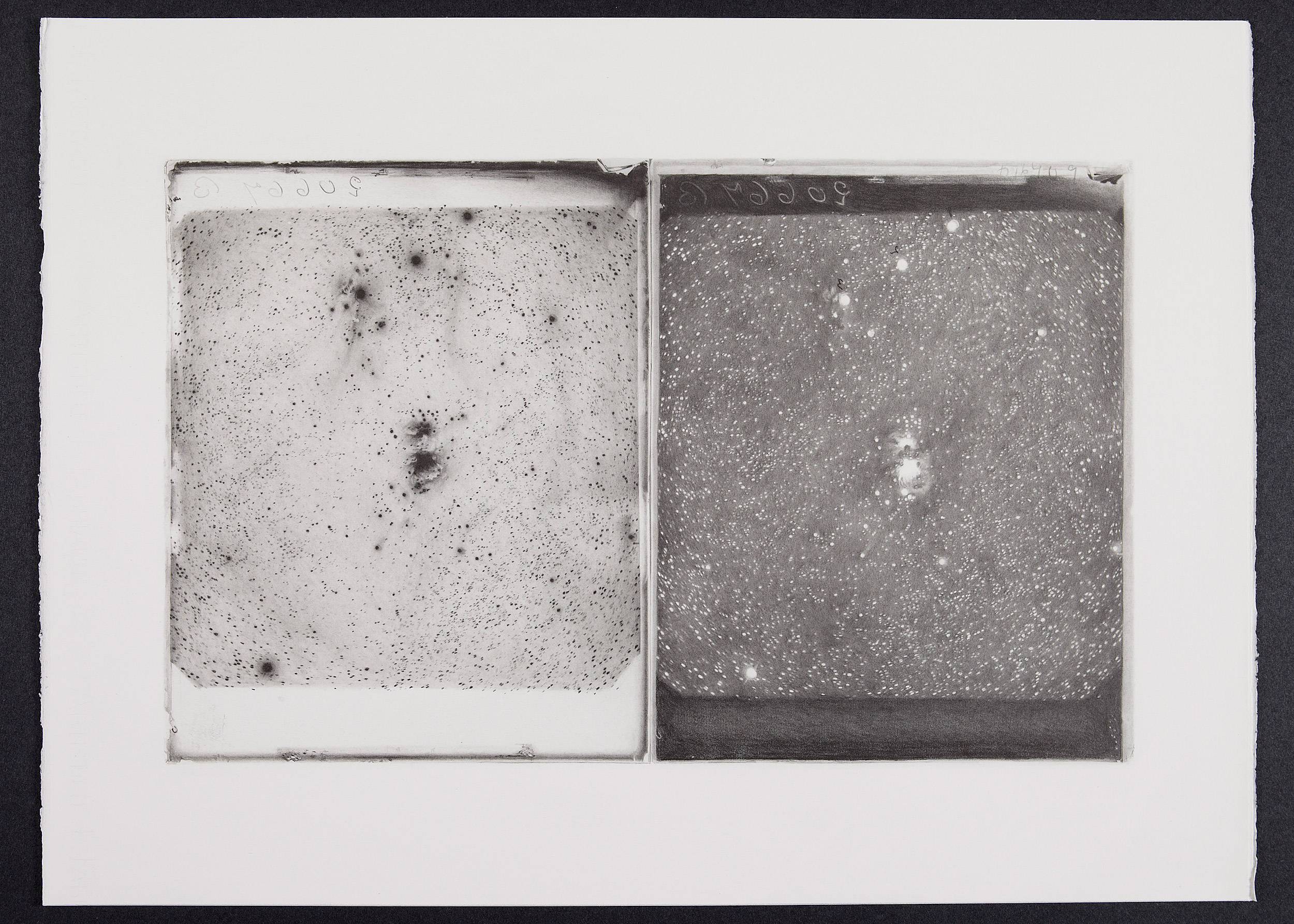

Other items in the show include Von Mertens’ pencil drawing of two glass plates featuring the Orion Nebula and quilts from her earlier “Shape/View” series.

Courtesy of the artist and Elizabeth Leach Gallery

Von Mertens’ exhibit recently provided the backdrop for a performance that included readings, mindfulness exercises, singing, and interpretive dance.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Story is key to the artist’s flow, and Leavitt’s life and career fueled the creative process. “If there isn’t some story and if there isn’t some idea that is with me along that path, I don’t get as engaged in the materials,” said Von Mertens. “But if I have that story, it feels like I am almost embedding that story into the material and then allowing that object to carry the story forward.”

Upon being asked to create the exhibition, Von Mertens, whose work relies on careful research, turned to Harvard’s galleries and archives for inspiration. The Schlesinger Library’s collections moved her to consider the voices of “these women that were not heard.” At the Harvard Observatory, Leavitt’s story stood out. “She was obviously so gifted and sharp, and she obviously saw things so uniquely, but there was really no vehicle for her voice,” said Von Mertens.

The works on view evoke the process of careful, precise repetition and pattern recognition required in Leavitt’s observations of space. They also ask viewers to consider questions, said Von Mertens, such as “What meaning is held in a single life?” and “What meaning is held in a single action, and what meaning is built with the repetition of that action?”

“This exhibition is built on many units of measurement: the length of a single stitch, the density of lead in a 2H or 3H pencil, the distance a beam of light travels in a year, the brightness of a single star, the span of a life lived,” notes Von Mertens in the show’s catalog. “Each unit alone holds something: the echo of its making, the marking of time, the beauty of its specificity. Each unit accumulated gains something; with repetition, form takes shape, and shape takes meaning.”

Other works in the show include her earlier “Shape/View” series, a number of similar cosmic panels inspired by our galaxy’s supercluster, as well as a pencil drawing of two glass plates featuring the Orion Nebula, a cloud of gas and dust in the Milky Way where Leavitt once searched for pulsating stars.

For some, quilting may seem an unusual avenue for artistic expression, but Von Mertens was hooked the minute she fashioned her first patchwork quilt out of old Salvation Army dresses. “I think a lot of people make one quilt in their lives and think ‘that was enough of that,’” said the artist. “I was completely taken with the process. There was this richness to the context, but also the materials themselves that I responded to so immediately that I just knew from that point forward that I wanted quilts to be how I worked.”

The idea to focus on the night sky came to her several years ago as she considered what it meant to hang her quilts for viewers, she said, and as she realized the wall “wasn’t [only] paintings’ terrain, it was about the act of looking.”

“And what is the most quintessential form of looking? … To me it was stargazing.”