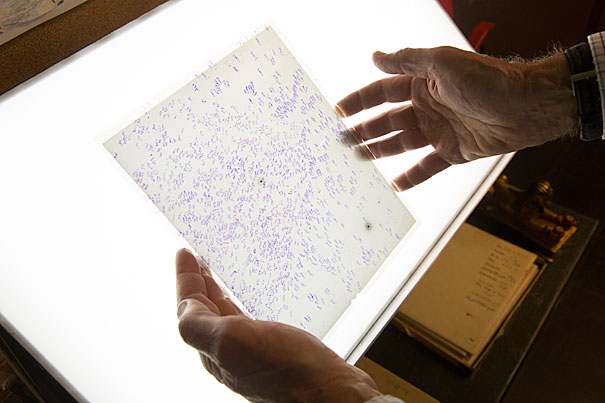

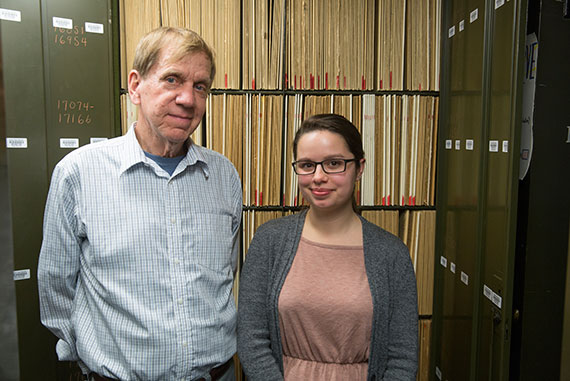

The glass plates collection at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics serves as a record of skies around the world across more than a century. Jonathan Grindlay is heading up a restoration effort after a January flood threatened the fragile plates.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Guardians of the sky

When flooding threatened 100-plus years of astronomical data, fast action was the only option

It was 16 degrees on a January night, the cold made worse by the fatigue of working so many hours. Box after box, heavy with glass, had to pass through the basement window, into the snow-covered parking lot.

But if the cold made for deep discomfort — and chattering teeth — it also proved a disaster-recovery ally after a water-main break flooded the Harvard College Observatory’s Plate Stacks, a unique historical treasure holding hundreds of thousands of glass plate negatives that serve as a record of skies around the world across more than a century.

By the time the flooding was discovered, early on Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the lowest level of the three-story stacks had been flooded to three feet, immersing 61,000 of the negatives and derailing the Digital Access to a Sky Century at Harvard (DASCH) project, a decade-long scanning effort aimed at making the plates more accessible for study.

The flood also soaked the custom-built digital scanner at the heart of the project. But the plates themselves were the main concern. With those in good repair, everything else would be OK.

“This collection is unparalleled, in my opinion,” said Brenda Bernier, who is the James Needham Chief Conservator and head of Harvard Library’s Weissman Preservation Center and Collections Care. “It’s the depth and breadth of the data, it’s extraordinary. The scale — hundreds of thousands of one of the most vulnerable formats.”

Bernier credited the Harvard Library Collections Emergency Team and photograph conservators Erin Murphy and Elena Bulat with understanding that the chill could aid the rescue effort. With the plates stored in soaked paper sleeves, the biggest danger to the photographic emulsion was mold. Mold spots would mar a record that consists of thousands or even many tens of thousands of pinpoints of light. The best course, the team decided, was to get the plates into the sub-freezing air as quickly as possible.

Since that night, the plates have been kept safely frozen and the mold at bay. They were transferred into refrigerated trailers, which are now stored with a North Andover company that specializes in document recovery. Early tests have suggested the photographic emulsion that coats one side of each plate will survive unaltered.

Conservators are working with Jonathan Grindlay, the Robert Treat Paine Professor of Practical Astronomy, and others at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) to devise a process for restoring the plates. These will include extracting them from the paper sleeves, which have to be photographed because they include data critical to interpreting the images, and then cleaning them of silt and grime. The methods devised at the Weissman Preservation Center, Bernier said, will be taught to technicians at Polygon in North Andover, who will carry out the restoration work, which is expected to take a year and a half.

Grindlay, who heads the DASCH project, and CfA director Charles Alcock expressed deep appreciation for both the tireless efforts of staff members and the expertise of the Harvard Library team.

“People were cold and tired, but not one was dropped,” Alcock said. “I’m very encouraged so far — it’s not a good thing to go through, but the response has gotten us to a good place with respect to the flood.”

Grindlay first imagined the scanning project in the 1980s, realizing that it would have to wait until computers were sophisticated enough to handle the enormous amount of data the plates contained, more than a petabyte.

DASCH launched in 2004, with the first scans made in 2006. The project has covered about a third of the 525,000 plates, the first of which was shot in 1885 and the last in 1992. The data hold value for astronomers who are interested in changes in particular stellar objects, each of which was photographed between 500 and 3,000 times over the years. Findings have so far appeared in about 100 papers, Grindlay said.

“There’s a tidal wave waiting to happen. There’s an enormous amount of data waiting for analysis.”

Grindlay was at the CfA the night of the flood, having secured remote observation time on the Multiple Mirror Telescope on Mount Hopkins in Arizona. He and two grad students were collecting data about extreme variable stars they had identified through DASCH.

At around 7 in the morning, Lindsay Smith, a senior curatorial technician, arrived at the plate stacks to calibrate the scanner for the day’s work. The building felt cold. When she descended the spiral staircase to the basement, she saw a couple of feet of water. Building manager Charles Hickey, who played a key role in the recovery effort, called the city of Cambridge to close the pipe. Workers later found that an eight-inch water main in the courtyard outside had ruptured 16 feet underground, sending muddy water though the soil and along the building’s foundation until it found a way in.

Emails were sent out asking for help. Grad student Jane Huang was among the 17 responders who worked through the first night of the recovery and the 50 who worked in shifts over three days.

“I knew my school needed help so I thought it would be good to pitch in,” Huang said.

Edward Pickering, the Harvard College Observatory director who got the sky photography project going in the 1800s, was a bit paranoid that something would happen to the plates, Grindlay pointed out. He had the building specially made to hold up their weight — 170 tons — and oversaw the installation of sliding steel doors that could close rapidly in case of a fire.

A new, faster scanner will arrive in May. It’s conceivable, Grindlay said, that the project could still end on time in 2018.

“I hope we’ll be able to catch up.”