The Sussex Declaration.

West Sussex Record Office Add Mss 8981

Declaration of authenticity

Analysis shows Sussex parchment was produced in 1780s, provides other clues to its past

From the first moment they saw it three years ago, Emily Sneff and Danielle Allen suspected that the Sussex Declaration would become a significant find as a late-18th-century copy of the Declaration of Independence. Now they have the evidence to back that up.

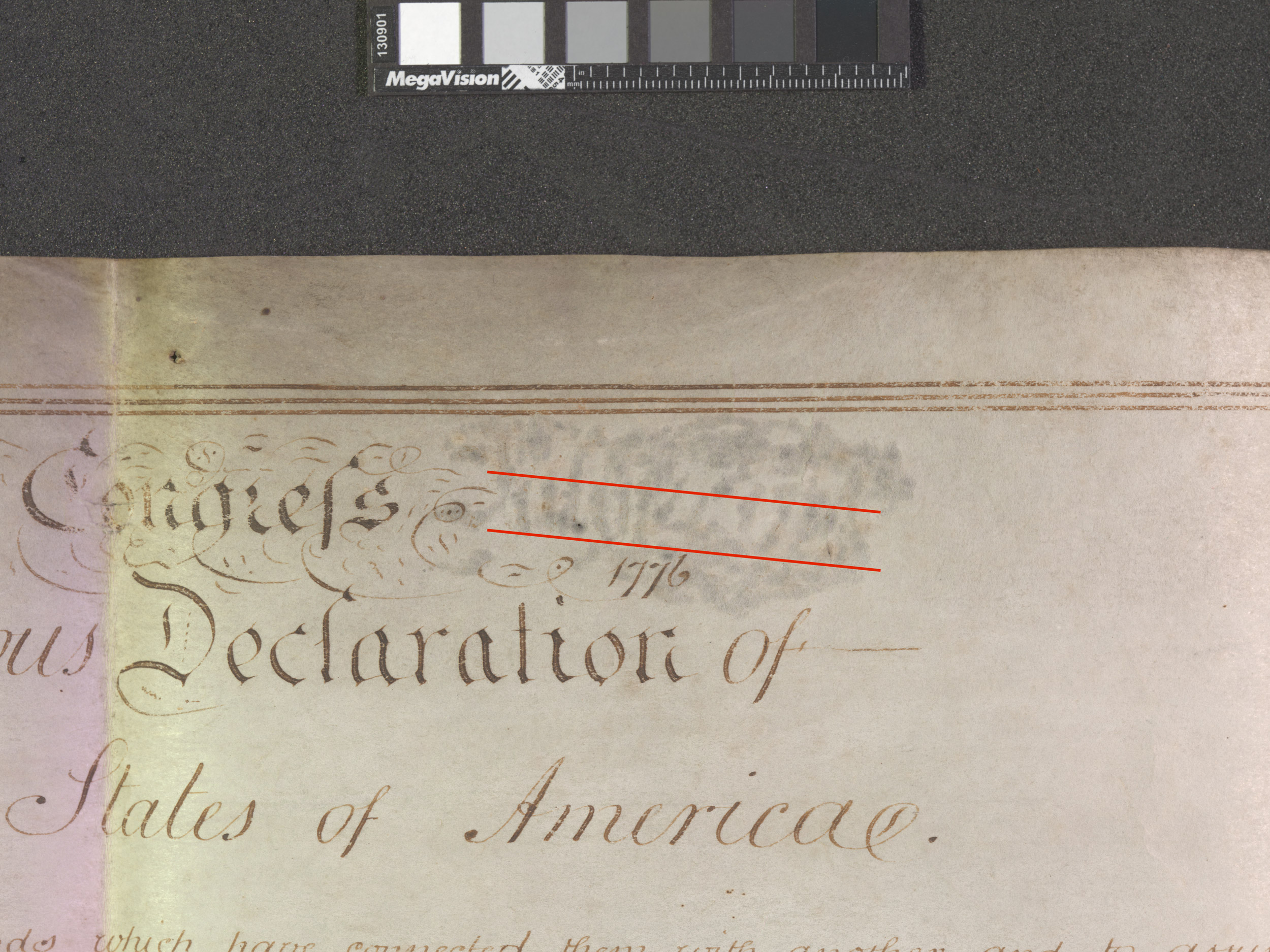

Working in collaboration with researchers at the West Sussex Record Office, the British Library, the Library of Congress, and the University of York, Sneff, the research manager for the Declaration Resources Project, and Allen, Harvard’s James Bryant Conant University Professor and director of the Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, completed a series of tests on the parchment document that revealed a date, either “July 4, 178” or “July 4, 179.”

Found just beneath a scraped erasure to the right of the document’s title, the date was uncovered using a number of high-tech analytical methods, including multispectral imaging, X-ray fluorescence (XRF) capture, and protein analysis (DNA testing).

The 24-by-30½-inch Sussex document is one of just two known roughly contemporary manuscripts of the Declaration of Independence on parchment. The other is the engrossed one signed by the delegates to Continental Congress, held at the National Archives in Washington, D.C. Unlike that document, the Sussex lists the signatories in the hand of a single clerk. There are other printed parchments of the declaration, and other handwritten versions of it. But these two are the only ceremonial parchment versions.

Though it is impossible to say whether there was originally a fourth digit in the year listed on the Sussex document, the finding supports Allen and Sneff’s hypothesis that the document was produced in the 1780s. The results also support their argument, laid out in a forthcoming paper in the Proceedings of the Bibliographic Society of America, that the clerk preparing it was inexperienced. Analysis revealed that the erased date was written along a slight downward slant, indicating the clerk made two errors in the calligraphy for the date, one with regard to the date itself, using the year of its production rather than the year in which the declaration was enacted, and the other in failing to maintain a horizontal line.

Red lines show the downward slope of erased text on the Sussex Declaration.

Courtesy British Library

Imaging revealed that the inked lines establishing horizontal margins for the parchment, along with the lining of the parchment used by the clerk to keep the rest of the text aligned, were added after this failed inscription was scraped off. Tests showed congruency in the iron gall ink used throughout the document, indicating that the initial and corrected titling, the body of the text, the list of signatories, and the corrections in the text were written in a relatively short window of time, almost immediately.

In addition, XRF analysis discovered high iron content in holes in the corner of the parchment, providing supporting evidence for the use of hand-wrought iron nails to hang the document. The protein, or DNA, testing revealed that the parchment was prepared from sheepskin rather than more expensive calfskin.

Details of the analysis will be described in two papers co-authored by Allen, Sneff, and colleagues. The first, which will be published this fall in the Papers of the Bibliographical Society, uses handwriting analysis, examination of the parchment preparation and styling, and spelling errors in the names of the signers to date the Sussex document to the 1780s.

The second, which identifies James Wilson as the most likely commissioner, and preparation for the Constitutional Convention as the most likely context of production, will appear in the Georgetown Law Review. That paper argues that Wilson, or a political ally, likely commissioned this parchment as a part of advocacy for the federal Constitution.

The most interesting feature of the Sussex Declaration is its treatment of the list of names of signatories. In contrast to all other 18th-century versions of the declaration, on this parchment the list of signatories was not grouped by states. The team hypothesizes that this detail supported efforts, made by Wilson and his allies during the Constitutional Convention and ratification process, to argue that the authority of the declaration rested on a unitary national people, and not on a federation of states. That emphasis was a key point of contention in creating the U.S. Constitution.