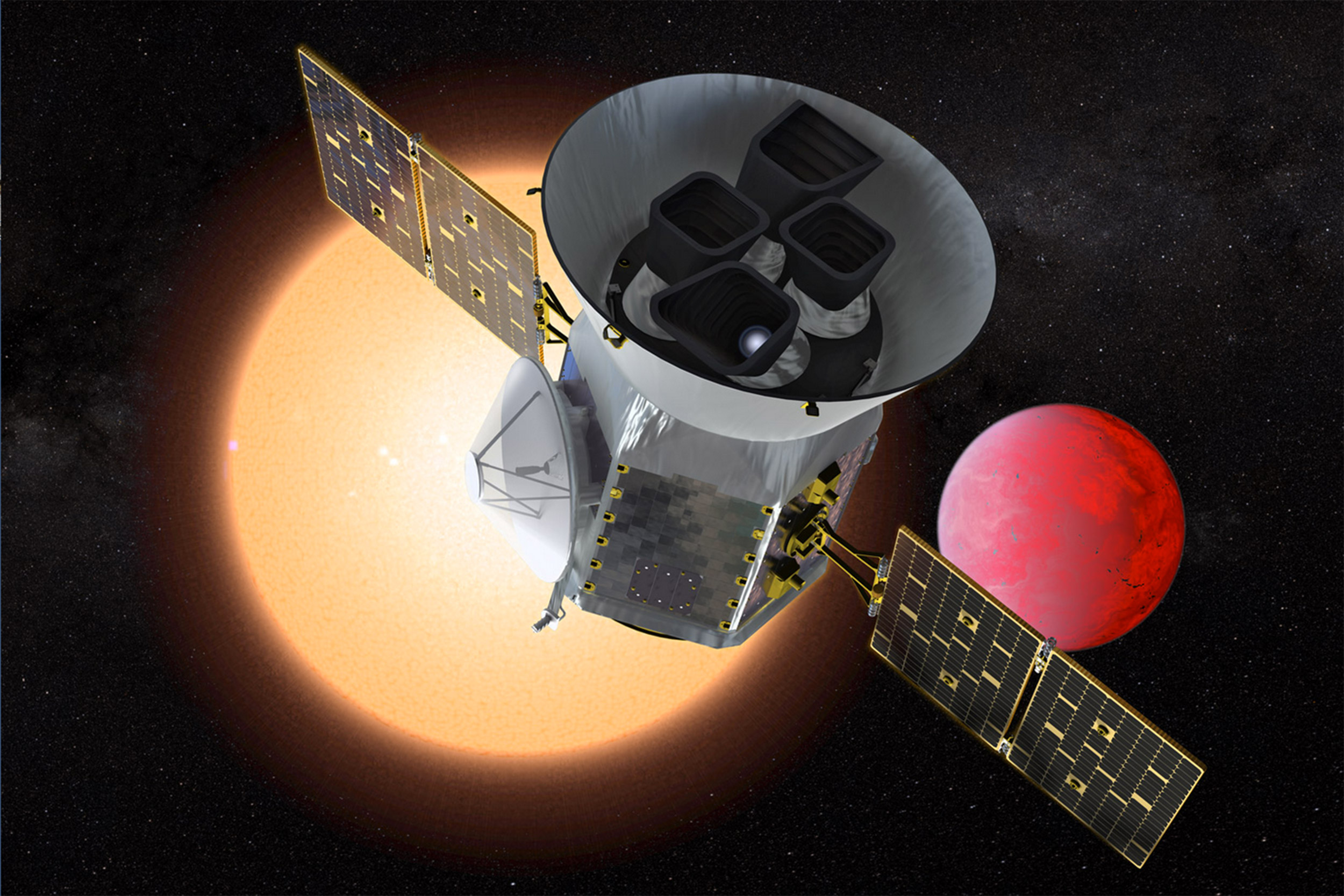

Illustration of the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) in front of a lava planet orbiting its host star. TESS will identify thousands of potential new planets for further study and observation.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

TESS to search the sky for new worlds

NASA’s satellite expected to discover planets whose atmospheric compositions ‘hold potential clues to the presence of life’

NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is undergoing final preparations in Florida for its April 16 launch to find undiscovered worlds around nearby stars, targets where future studies will assess their capacity to harbor life.

“One of the biggest questions in exoplanet exploration is: If an astronomer finds a planet in a star’s habitable zone, will it be interesting from a biologist’s point of view?” said George Ricker, TESS principal investigator at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, which is leading the mission. “We expect TESS will discover a number of planets whose atmospheric compositions, which hold potential clues to the presence of life, could be precisely measured by future observers.”

Dozens of scientists, including graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) will play key roles in TESS follow-up and the science the telescope is expected to achieve.

Following a successful March 15 review of the spacecraft’s launch readiness, TESS will be fueled and encapsulated within the payload fairing of its SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

TESS will lift off from Space Launch Complex 40 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. With a gravitational assist from the moon, the spacecraft will settle into a 13.7-day orbit around Earth. Sixty days after launch, following tests of its instruments, TESS will begin its initial two-year mission.

The spacecraft will be looking for a phenomenon known as a transit. Transits occur when a planet passes in front of its star, causing a periodic and regular dip in the star’s brightness. NASA’s Kepler spacecraft used the same method to spot more than 2,600 confirmed exoplanets, most of them orbiting faint stars 300 to 3,000 light-years away

CfA astronomer David Latham serves as the project science director, and will oversee the TESS Follow-up Observing Program. This program will include measuring the mass of 50 exoplanets with four times the radius of Earth or smaller. Another goal is to foster communication and coordination among the TESS science team and the community.

“Everyone in the TESS Science Office is excited,” said Latham. “We can’t wait to get our hands on TESS light curves of new transiting planets!”

TESS will concentrate on stars less than 300 light-years away and 30 to 100 times brighter than Kepler’s targets. The brightness of these target stars will allow researchers to use spectroscopy, the study of the absorption and emission of light, to determine a planet’s mass, density, and atmospheric composition. Water and other key molecules in its atmosphere can give hints about a planets’ capacity to harbor life.

The CfA will make follow-up observations of TESS targets using its MEarth telescopes, a pair of robotically controlled observatories, each comprising eight 40 cm telescopes, located at the Smithsonian’s Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory (FLWO) outside Tucson, Ariz., and on Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) in Chile. Astronomers will also use the CfA’s KeplerCam on the 48-inch telescope and the Tillinghast Reflector Echelle Spectrograph (TRES) at FLWO. The MEarth and KeplerCam observations will be used to confirm the star responsible for the transit events identified by TESS, and TRES will be used to track down false positives due to eclipsing binaries. TRES will also provide improved stellar parameters for the host stars, which is important because the radius of a transiting planet is relative to the size of the star it orbits. These observations at FLWO and CTIO will be critical for identifying the best candidates for very precise radial velocity observations with HARPS-N (the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher for the Northern hemisphere) on the Telescopio Nazionale Galileo on La Palma in the Canary Islands, which will be used to derive the orbits and masses of small planets.

Through the TESS Guest Investigator Program, the worldwide scientific community will be able to participate in investigations outside of TESS’s core mission, enhancing and maximizing the science return from the mission in areas ranging from exoplanet characterization to stellar astrophysics and solar system science.

In addition to the CfA, other partners include Orbital ATK, NASA’s Ames Research Center, and the Space Telescope Science Institute. More than a dozen universities, research institutes, and observatories worldwide are participants in the mission.

For the latest TESS news, visit its website.

The MIT funding comes from the TESS mission by way of the Goddard Space Flight Center.