Radcliffe fellow Chad Williams is working on a book about what he considers one of W.E.B. Du Bois’ greatest missteps: “The Black Man and the Wounded World,” an unfinished history of the African-American experience during World War I.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Retracing Du Bois’ missteps

Radcliffe fellow probes ‘tragedy’ of pioneering African-American scholar’s failed book on WWI

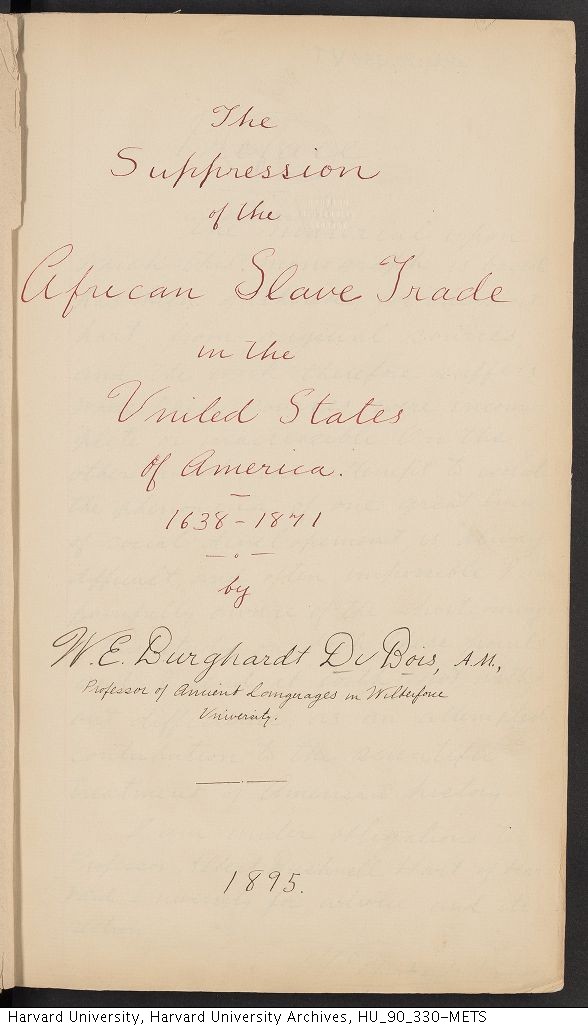

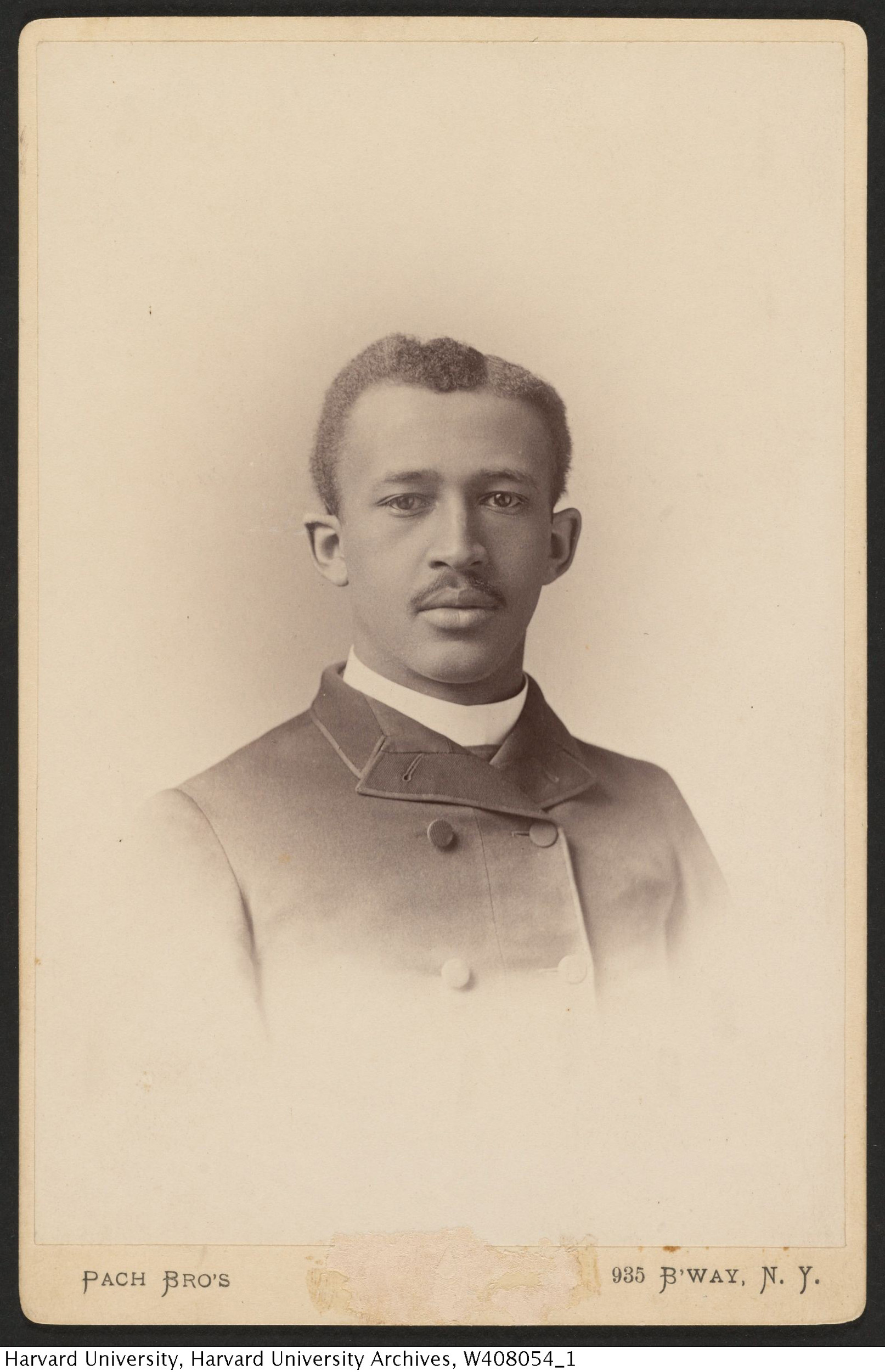

By any measure, W.E.B. Du Bois was an intellectual giant. A historian, writer, editor, teacher, sociologist, and civil rights activist, he was also the first African-American to receive a Harvard Ph.D., co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and author of several groundbreaking books, including “Black Reconstruction in America” (1935).

But according to historian Chad Williams, Du Bois was also a failure.

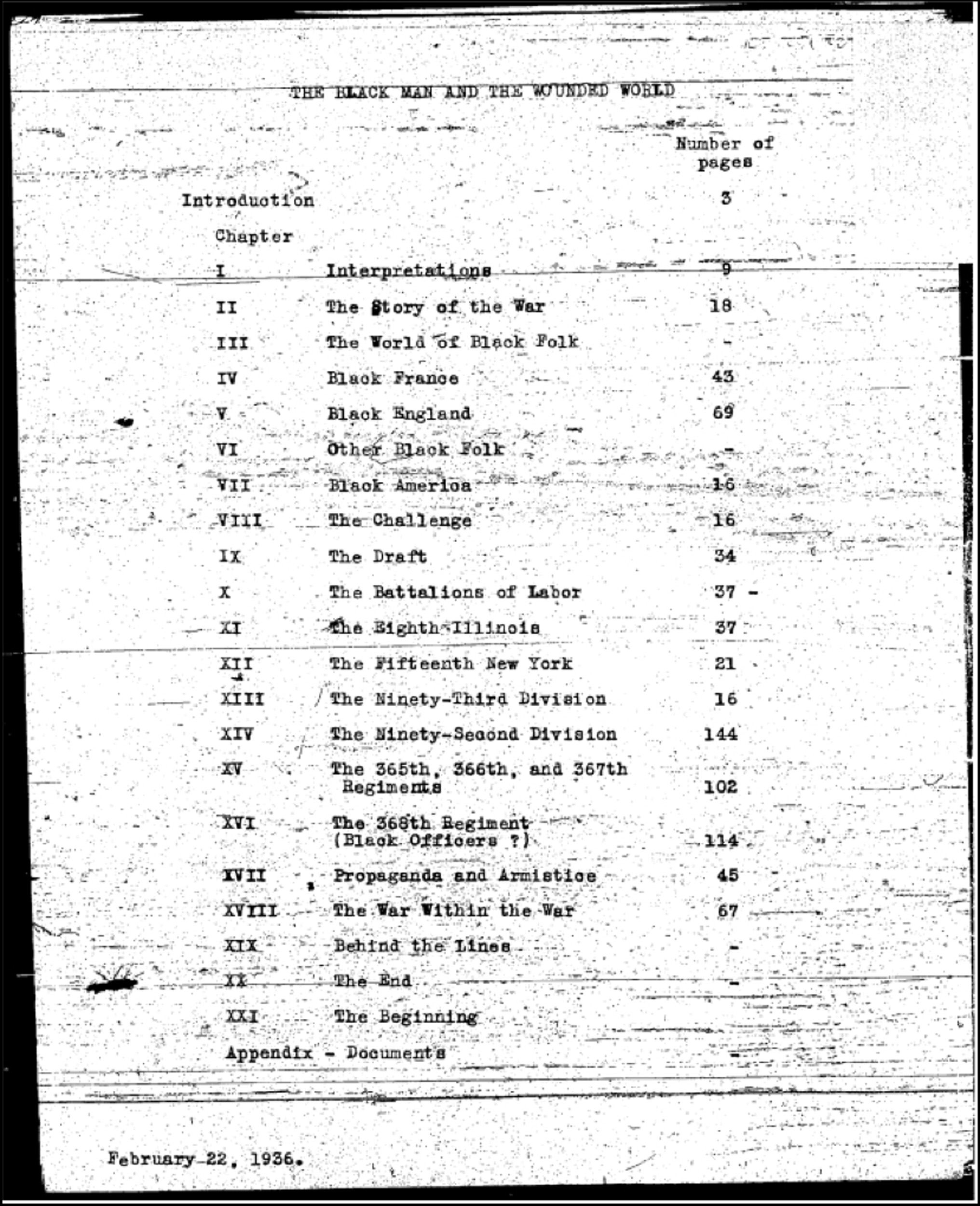

As a fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Williams is writing a book about what he considers one of Du Bois’ greatest missteps: “The Black Man and the Wounded World,” an unfinished history of the African-American experience during World War I. Unlike many civil rights crusaders of the time, Du Bois urged African-Americans to join the war effort. But when acts of loyalty and heroism in Europe failed to translate to the societal change he’d envisioned back home, he began documenting the results of his misjudgment.

“Du Bois as a failure … that’s a framework for thinking about him that I would never have really considered,” said Williams, chair of African and Afro-American studies at Brandeis University.

Williams came across Du Bois’ incomplete manuscript at UMass Amherst in 2000 while researching the Ph.D. dissertation that would become his 2010 book, “Torchbearers of Democracy: African American Soldiers in the World War I Era.” His years spent poring over Du Bois’ archives and records helped Williams understand the professional and personal dimensions to Du Bois’ failings. The inability to finish the book was a source of deep frustration, while his support of the war and his belief in what the conflict could have meant for equality in America haunted Du Bois till his death.

“The war was one of the most consequential and traumatic moments in his life as far as his wrestling with what it meant to be an African-American,” said Williams. “What he talks about in his 1903 book, ‘The Souls of Black Folk’ — the ‘double consciousness,’ the twoness of being a Negro and being an American, these two warring ideals. Du Bois thought that the war would be able to, at least temporarily, reconcile those two conflicting aspects of black identity more broadly, but also personally, and that didn’t happen.”

More than 350,000 African-American soldiers served in segregated units during World War I. Most of the black troops stationed in France were assigned to ditch digging or the bearing of dead bodies. In time, the Army created two African-American combat units, the 92nd division made up of draftees, and the 93rd that comprised black national guardsmen. While the 93rd “compiled a stellar combat record,” the 92nd floundered.

Image 1: Cover page of Du Bois’ Harvard dissertation ” The suppression of the African slave trade in the United States of America, 1638-1871.” Image 2: Du Bois’ photograph from the Harvard College Class of 1890 Class Book.

Courtesy of Harvard University Archives; (2) Pach Bros., New York, New York, United States [photographer] ca. 1890

“Racist white commanders and deliberate neglect from the War Department doomed the performance of the division from the start, while its black officers … endured humiliation after humiliation,” Williams said in a Radcliffe talk in the fall.

Du Bois initially saw “Wounded World” as way to stem the outcry over “Close Ranks,” an editorial he’d written in July 1918 for the NAACP monthly journal The Crisis in which he called for African-American soldiers to temporarily put aside their grievances and join up with the Allied forces in the name of democracy. Critics branded him a traitor to his race. Du Bois was shaken by the rebuke.

“He viewed writing this book as a form of personal and political redemption … that he would be able to rehabilitate his credibility through writing the history of the black experience in the war,” said Williams.

But the project took on an even deeper meaning when Du Bois interviewed African-American soldiers in France after the fighting. They recounted the “horrific racism and discrimination they had endured,” at the hands of fellow servicemen, said Williams. From that moment on the project became one of “reclamation.”

African-American soldiers fighting in WWI pose for a company photo.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Du Bois is aware that the official historical record is going to marginalize the contributions and sacrifices of African-American soldiers and officers in particular, and that it’s necessary to tell this history correctly.”

Yet that effort led to another failed opportunity, and a breach of trust. In his drive for accuracy, Du Bois sent out a call for African-American veterans to send him material related to their experiences. Letters, diaries, and other documents poured in. Their willingness to share information showed they were “investing their hopes and historical visions in Du Bois,” said Williams. “In the end, those untold stories are part of the real tragedy of this project.”

Du Bois’ disillusionment with the war reached its peak in 1930s during travels in Russia, China, Japan, and Germany. The rise of fascism and militarism in Europe and elsewhere convinced him that the condition of the world “was almost irredeemable,” said Williams. Any lessons his book could offer would be “almost too late,” he decided.

While Williams referenced Du Bois’ World War I material in his 2010 book, he knew the manuscript, 800 pages written over the course of 20 years, was something to which he “would inevitably turn back.” In an increasingly polarized U.S., Williams thinks a closer examination of Du Bois’ unfinished work can offer important lessons not only to scholars but also to the wider public.

Image 1: Williams holds a photo of a WWI African-American soldier from Du Bois’ collection. Image 2: Table of Contents for “The Black Man and the Wounded World” (unpublished, 1936).

(1) Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer; (2) W.E.B. Du Bois Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Fisk University

“One hundred years later we are still reckoning with the legacies of World War I, particularly in terms of race and democracy — the same challenges that Du Bois wrestled with,” he said. “What does it mean to be African-American? That’s still the fundamental question for many people, along with how we try to heal the wounds of our still very wounded world.”

And though Williams ultimately calls the story of the unfinished manuscript “a tragedy,” he sees hope in Du Bois’ failure.

“I think it’s instructive for us and for me as a historian to know that Du Bois, for all of his brilliance and clairvoyance, was genuinely confused by this moment, and to the end of his life was unsure if he made the right decision in supporting the war.

“If there is any hope to take from it, it’s the struggle that Du Bois was engaged in and the commitment that he had, which I think is a commitment that we all must have — especially today, when we see democracy itself being undermined and attacked and we see white supremacy resurgent and being legitimized at the highest levels of our democracy.”