“Four people will die from overdoses in the time we’re having this conversation today,” U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams told the Harvard Chan School audience during a 30-minute webcast.

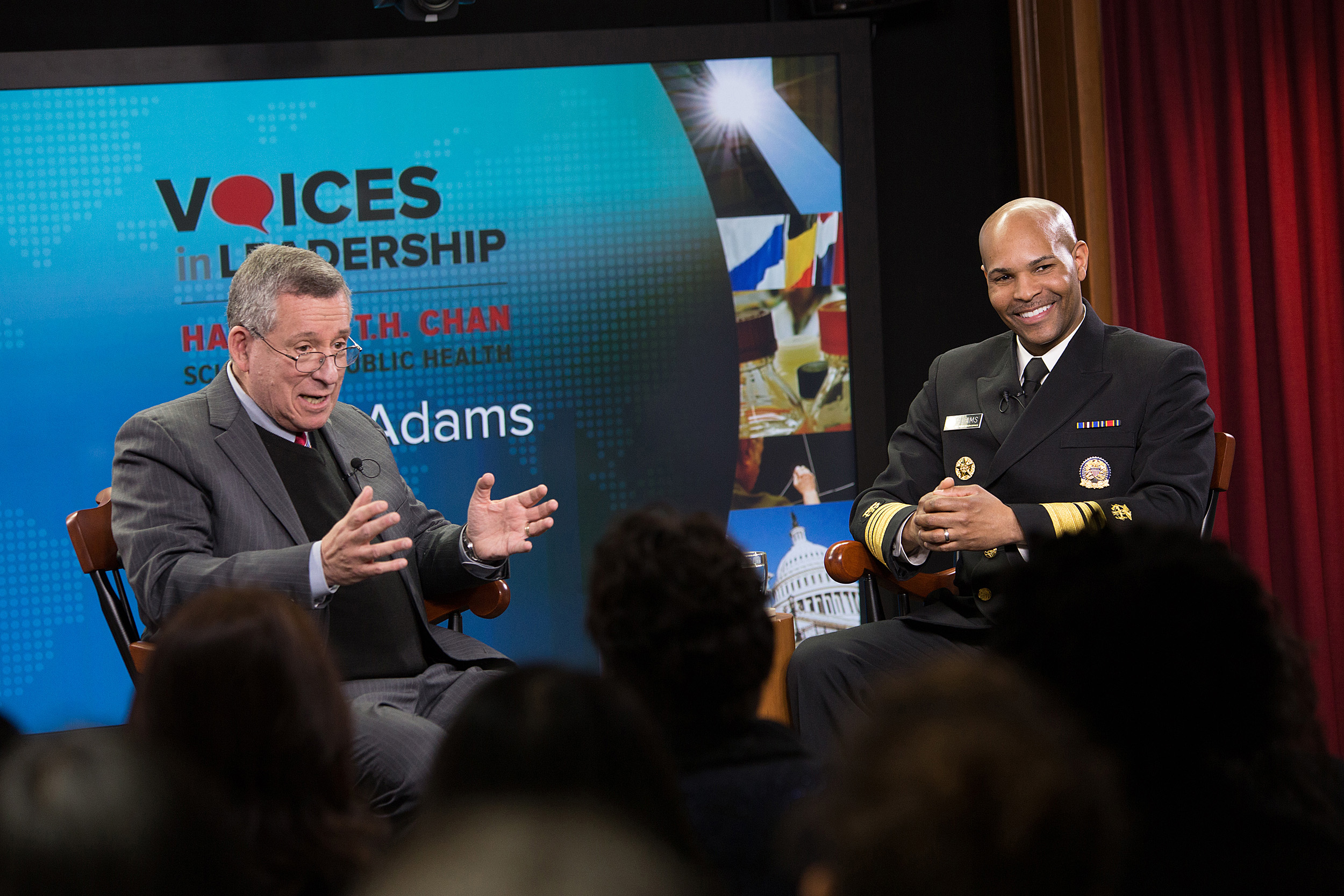

Photos by Sarah Sholes/Harvard Chan School

Opioid epidemic top priority for surgeon general

Adams addresses nation’s health at HSPH leadership event

The opioid epidemic is U.S. Surgeon General Jerome Adams’ top priority and his position’s bully pulpit is his most potent weapon to effect change.

Because of that, Adams has publicly shared his own family’s struggle with addiction, which includes a brother who has been jailed as he fights substance abuse.

Adams described the opioid epidemic as an “all hands on deck” crisis, needing not just health care providers, but also mothers, fathers, even children: He tells his three kids to talk about their uncle’s plight with classmates, in hopes it will help them make good choices.

“Four people will die from overdoses in the time we’re having this conversation today,” Adams said Wednesday at a Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health “Voices in Leadership” webcast. “That’s what I’m focused on foremost.”

In the 30-minute program, Adams responded to questions from Robert Blendon, the Richard L. Menschel Professor of Public Health, professor of health policy and political analysis, senior associate dean, and director of the Division of Policy Translation and Leadership Development. Adams, an anesthesiologist who served as Indiana state health commissioner from 2014 to 2017, was nominated as surgeon general by President Trump in June and confirmed by the Senate in August.

Adams said the surgeon general’s main role is heading the U.S. Public Health Service, a corps of 6,500 doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and environmental health and other officers. Public Health Service officers responded to the disasters of 9/11; to last fall’s catastrophic hurricanes in Texas, Florida, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands; and even internationally, during the West African Ebola epidemic.

But Adams said he cannot neglect the surgeon general’s influential position as the nation’s top doctor, and the importance of communicating to the public and policymakers about important public health issues. Adams said he thinks the surgeon general’s office can do a better job communicating with the public. When it comes to advising policymakers, he said it’s important to understand the difference between science and policy and to find the “sweet spot” where they overlap and opportunities for change exist.

To fight the opioid epidemic, Adams wants to increase the availability of naloxone, a drug that can reverse the effects of opioid overdose. While some argue that its easy availability would encourage opioid abuse, “As a physician, when people are dying, when you come across a trauma scene, you’ve got to put on a tourniquet. Naloxone is that tourniquet,” Adams said.

Adams said that a January public opinion poll by Blendon and John Benson, a senior research scientist at HSPH who works with Blendon at the Harvard Opinion Research Program, where he’s managing director, showed that 52 percent of the public thinks naloxone should only be available by prescription.

“Fifty-two percent of people wouldn’t say that you shouldn’t know how to do first aid at a scene when you come upon an accident. We have to help folks understand that naloxone saves lives and that it’s a critical first step to connecting people to care,” Adams said.

Treatment works, Adams said, but it’s important to connect people to qualified programs, with access to proven medications such as buprenorphine, naltrexone, and methadone. In addition, he said a broad array of physicians, as well as nurses, therapists, and others who can potentially detect and intervene, should be trained in substance abuse disorders.

“I call on my colleagues, I’m talking about all health providers, to figure out how they can be part of the solution,” Adams said. “We’re never going to dig out from under this if we rely on just the folks who have specialized training and residency to be able to respond. We’ve got to a better job of enabling more folks to be able to respond because we can’t train [specialists] fast enough. What we need to do is take the people who are out there and enable them to provide that care.”

Beyond the opioid epidemic, Adams said he wants to highlight the connection between health and the economy, calling poor health in the U.S. a “drag on our nation’s economy and our nation’s prosperity.” Another focus will be on health and national security. Adams said 70 percent of 18- to 25-years-old Americans are ineligible for military service, mainly because they can’t pass the physical.

“Our poor health is not only a matter of diabetes 20 years down the road, or a heart attack 30 years down the road. We are a less safe country right now because we are a less healthy country than what we know we could be, and should be,” he said.