Harvard researchers have found evidence that oxytocin, often called the “love hormone,” plays a crucial role in helping the brain process social signals and decide what requires attention and what can be relegated to the background.

Credit: Trifonenko/iStock

A volume control for the brain

Study shows how oxytocin helps the mind modulate social stimuli

With so many sights, sounds, smells, and other stimuli, the brain is flooded by the moment. How can it sort through the flood of information to decide what is important and what can be relegated to the background?

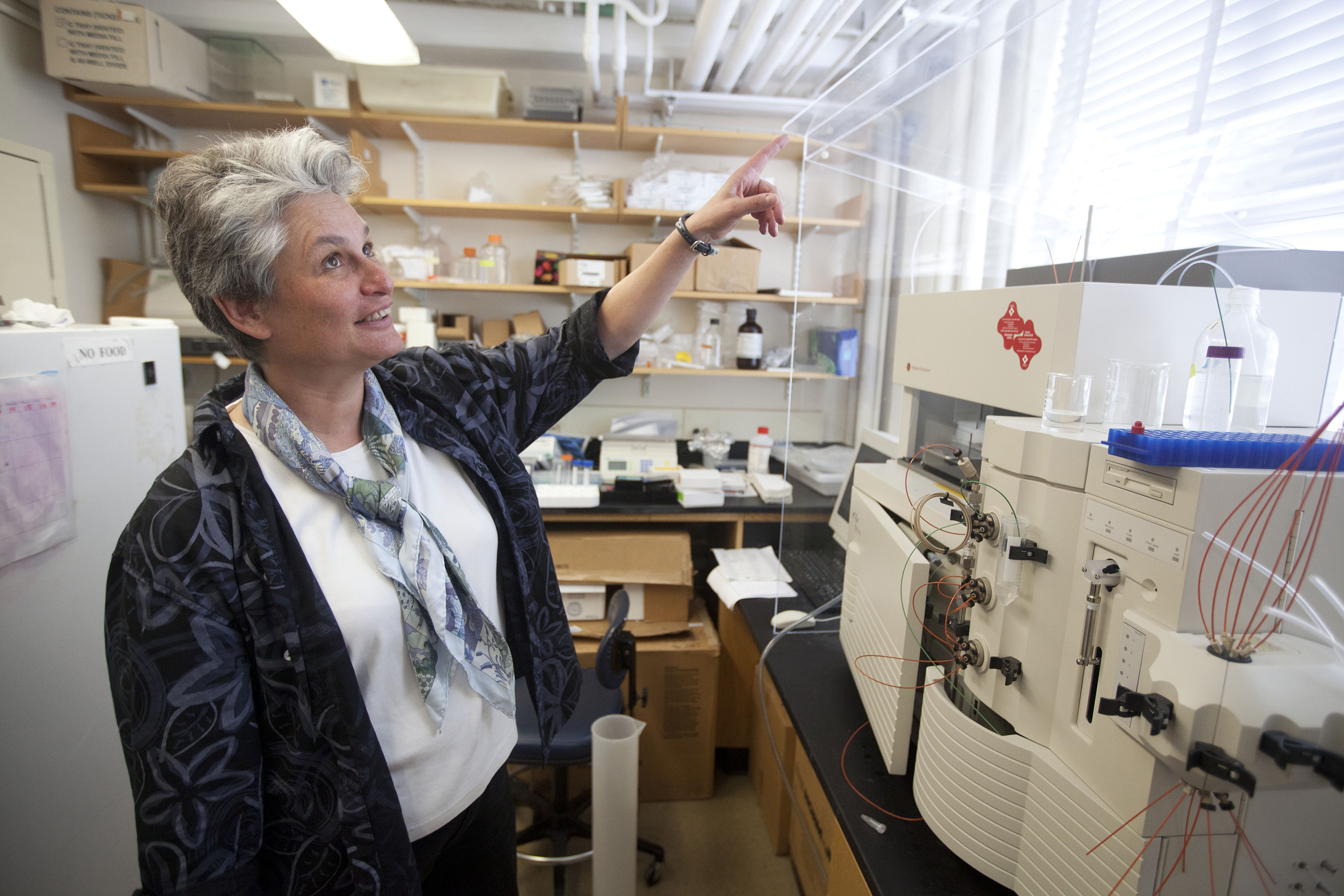

Part of the answer, says Catherine Dulac, the Higgins Professor of Molecular and Cellular Biology, may lie with oxytocin.

Though popularly known as the “love hormone,” Dulac and a team of researchers found evidence that oxytocin plays a crucial role in helping the brain process a wide array of social signals. The study is described in a recent paper published in eLife.

The study, Dulac said, suggests that oxytocin acts like a modulator in the brain, turning up the volume in certain stimuli while turning it down in others, helping the brain make sense of the barrage of information it receives.

In investigating the role of oxytocin in processing social signals, Dulac and colleagues began with an obvious behavior: the preference of male mice to interact with females.

Studies have shown that this behavior isn’t just social. It’s hard-wired into the male mice’s brains.

When male mice were exposed to the pheromone signals of females, Dulac and colleagues found, neurons in their medial amygdala showed increased levels of activation. When the same mice were exposed to pheromones of other males, the neurons showed relatively little stimulation.

Armed with that data, Dulac and colleagues targeted the gene responsible for producing oxytocin, which is known to be involved in social interactions ranging from infant/parent bonding to monogamy in some rodents.

Using genetic tools, researchers switched the gene off and were surprised to find that both males’ preference for interacting with females and the neural signal in the amygdala disappeared.

“This is a molecule that’s involved in the processing of social signals,” Dulac said. “We also showed, using pharmacology and genetics, that the effect happens on a moment-to-moment basis.

“What we are trying to do is understand the logic of social interactions in one particular species,” she said. “What this study says is, for this particular type of social interaction, oxytocin plays a role, and that role is both at the level of the brain and the behavior.”

Understanding oxytocin — and molecules like it — might shed light on a number of brain disorders.

With an understanding of how neurotransmitters work to amplify or quiet stimuli, Dulac said, researchers may gain insight into how to treat everything from depression, which is often characterized by a lack of interest in social interactions, to autism, which is thought to be connected to an inability to sort through social and sensory stimuli.

Ultimately, Dulac said, the study offers a glimpse into what could be a larger system of molecules that act as modulators in the brain, turning some stimuli up or down depending on the situation.

“There may be many different regulators,” Dulac said. “Oxytocin might be one of a whole realm of modulators, each of which is important in a particular circumstance. That therefore gives the animal a great deal of plasticity in terms of engaging in a particular behavior, so it’s not the case that each time the animal encounters a particular stimulus it will react in exactly the same way. Depending on the state of the brain and the release of these neurotransmitters, the animal can boost its behavior toward the stimulus or ignore it.”