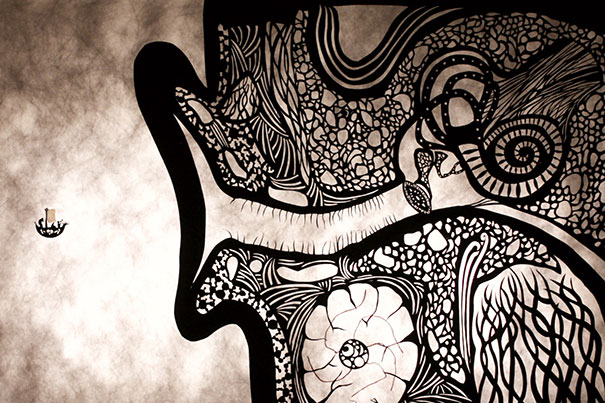

Artistic collaborations like those with papercut artist Andrew Benincasa punctuated lessons in part three of “Fundamentals of Neuroscience.”

Courtesy of HarvardX

‘The story of us’

By animating our minds, brainy HarvardX MOOC aims to democratize science

More like this

Somewhere in Senegal, or maybe France, a student taking the HarvardX course “Fundamentals of Neuroscience” is anesthetizing a cockroach and studying the insect’s legs, in order to watch the electric patterns and hear the sound of its neurons at work.

You couldn’t ask for a better illustration of course creator David Cox’s belief that science is for everybody and, at its best, a DIY-endeavor.

Initially rolled out three years ago, “Fundamentals of Neuroscience” was one of the first MOOCs (massive open online courses) offered by HarvardX and it remains one of the most ambitious, both for its subject matter and its presentation.

It’s also been a popular success, with participants from more than 150 countries at last tally. The course, more like a sequence of stackable or standalone modules, has seen more than 210,000 unique visitors spend 120,000 hours exploring it.

“We cover the full range of biophysics, from the smallest part of a neuron up to the collective action of the brain,” says Cox, assistant professor of molecular and cellular biology and of computer science. “It’s a big, broad survey that builds up to the full organism, and we’ve organized the course from small to big.”

Three of four planned parts have been offered so far: “Electrical Properties of the Neuron” covers the fundamentals of how the components work; “Neurons and Networks” shows how they interact with each other; and “The Brain” examines how the organ functions and how sensory perception works.

But when those concepts are translated into the online format, the real fun begins. And yes, fun is the operative word: Cox and his collaborators favor a vibrant visual and directorial style for their course, taking full advantage of multimedia. The course sections come with futuristic synthesizer music, moving charts and graphs, and fanciful animations.

One such piece, “The Synapse” — produced and narrated by Nadja Oertelt, the course’s original senior project lead and producer — verges on the psychedelic with its Claymation imagery. Deep red electric charges shoot through the animated brain, a floating skull and crossbones represent psychic disorders, and, when Oertelt mentions how perception is seasoned over time, a guiding hand “opens” the head and seasons the brain with a shaker of salt.

“I think that it’s arbitrary to make a distinction between what is entertaining and what is educational,” Oertelt says. “The reality is that we need a more diverse scientific workplace, and we need to open that space to everybody. The way to do that is to make it feel friendly, not like something only a faculty member could understand.”

Cox met Oertelt when both were at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he as a graduate student and she as a research assistant. She is currently a senior producer at the digital media website Mashable. Both were inspired by the educational TV they grew up watching, and Cox credits Oertelt for giving the course its coherent look and feel.

And lest you conclude that online education isn’t brain surgery, sometimes it is. For one grittier segment, Oertelt interviewed a patient with Parkinson’s disease, and the camera followed the patient into the operating room where he received deep-brain stimulation to improve his motor functions.

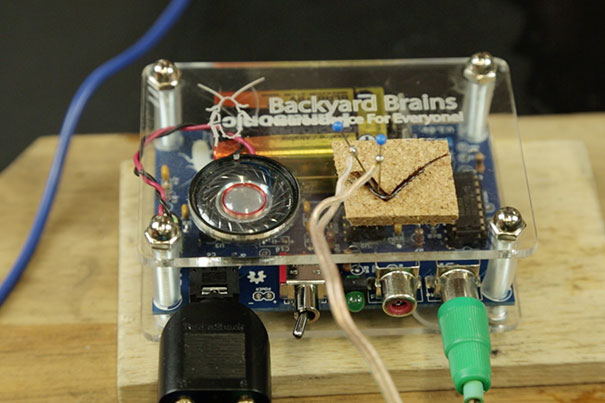

Students were invited to do experiments at home using a “spiker box” developed by Backyard Brains that allows anyone to see and hear insects’ neurological activity — something previously not possible outside a well-equipped lab. Visual perception was investigated through the lens of the Harvard Art Museums’ Rothko show.

Photos courtesy of HarvardX

The course also visited Harvard’s Warren Anatomical Museum — the home of the skull of Phineas Gage, a 19th-century railroad worker who survived an accident that sent a steel spike through his frontal lobe, prompting some of the first major brain research.

Students’ own brains get a workout through the course’s “guided interactivity” sections. In these, the video narrator presents a choice, and the students’ actions determine what happens next.

“The students don’t always realize these sections are coming,” Cox says. “We’ll lay out a topic and ask you to predict what you’d say if, for example, you increased the diameter of a neuron. And then we give you the simulation to see if your answer was right or not.”

Finally, the course invites students to do hands-on experiments at home. The partner group Backyard Brains has developed a “spiker box” that allows anyone to see and hear insects’ neurological activity — something previously not possible outside a well-equipped lab. If you isolate a cockroach leg, the box amplifies the actual sounds of the “spiking,” or neurological activity, of the still-living leg. An iPhone app allows you to watch the spiking patterns. You can even stimulate the neurons through music and make the leg move and dance.

“You’re basically eavesdropping on the cockroach’s nervous system,” Cox says. “When students try these experiments, it gives them a sense that they could be a scientist. And there is research showing that such students will do better in their exams and rate themselves as being more effective.”

The democratization of science is the course’s true agenda.

“The important thing to realize is that there’s no stable truth in science,” Oertelt says. “Every piece of knowledge that we teach and that the students take in is a product of hugely collaborative effort across time and space by scientists trying to get closer to some kind of physical truth. You’re not trying to discover some nugget. Instead you’re always questioning and testing hypotheses as to how the world works. That’s an ongoing process, and it’s something that the students can be part of.”

According to Cox, the course’s appeal is designed to be universal.

“Some people are viewing it as a recreational activity, and I have no problem with that,” he says. “What makes us unique is our brains, so it’s really something that everybody is interested in. At the end of the day, it’s the story of us.”