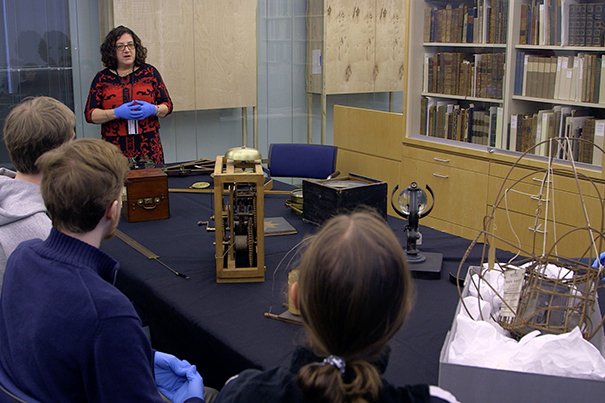

Professor Sara Schechner shows students compasses, sextants, and a variety of other instruments that sailors used to measure and predict their location at sea.

Photo courtesy of HarvardX

An academic reality show

‘PredictionX’ brings together faculty from across the University to discuss the human need to know the future

In a Science Center lecture hall at Harvard, anthropologist Rowan Flad heats a hot metal poker and touches it to a goat scapula.

The ancient Chinese, he explains, used a ritual similar to this as a means of divination. As early as 4000 B.C., they attempted to predict the future by reading the patterns created after the bone cracked from the poker’s heat.

But nobody could have predicted that “oracle bones” would be recreated millennia later, for a digital camera, in the name of Internet-enabled education.

That’s one small part of “PredictionX,” a HarvardX offering covering the history of prediction. Created by astrophysicist Alyssa Goodman, the modular learning experience traces humanity’s effort to understand the future — from ancient rituals to the scientific revolution to modern predictive simulations.

As such, it’s one of HarvardX’s most ambitious, interdisciplinary offerings to date. Goodman, the Robert Wheeler Willson Professor of Applied Astronomy, is even reluctant to define it strictly as a course.

“I wasn’t interested in doing an online course filled with just talking-head lecture-style video,” she explained. “But, in ‘Prediction,’ I saw the opportunity to create repurposeable modular materials, including plenty of interactive content such as dynamic maps, timelines, and simulations.”

Goodman was named scientist of the year by the Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations in 2015, and she was the founding director of Harvard’s Initiative in Innovative Computing. She also worked with Microsoft Research to help create WorldWide Telescope, an application that explores the Earth and the cosmos from a computer screen. She is using this application to create interactive maps for the course. In addition, Goodman and the “PredictionX” team are working on a Web-based, interactive timeline on the history of prediction, which itself will become a prototype for a more ambitious, multi-institution project enabling collaborative timelines to be crowdsourced online.

The video segments of “PredictionX,” many of which take the form of group discussions, are equally ambitious, bringing together faculty who typically don’t have good opportunities to collaborate. So far the effort involves more than a dozen faculty members from across Harvard, and several more are planning to come aboard.

“This represents what I see as one of the most exciting aspects of experimenting with new ways to teach,” said Michael D. Smith, the Edgerley Family Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “The opportunity for faculty to explore new collaborations, driven purely by affinity of ideas and interests, and to connect with faculty far from one’s own discipline — that’s really energizing. I’m delighted we also get to share our faculty’s excitement in this with the world.”

“PredictionX” was designed from the ground up as an online educational experience, rather than using a classroom course as the starting point. HarvardX course lead Drew Lichtenstein explained that a digital-first approach allows a kind of plug-and-play integration of ideas.

“The Aztec people would have never been able to talk to their Chinese counterparts about their divination systems, but, it turns out that there are recurring motifs,” Lichtenstein said. “Today, experts in Chinese divination mostly collaborate and talk with other scholars of Ancient China, but there are few opportunities for cross-cultural discussions and very little published comparative scholarship on prediction. So we’ve brought together work that different faculty members have done in their own separate research and teaching in very different fields.”

In “PredictionX,” due to launch its first module next spring, experts in fields ranging from the Old Testament (Laura Nasrallah, professor of New Testament and Early Christianity at Harvard Divinity School) to the Mexican serpent god Quetzalcoatl (David Carrasco, Neil L. Rudenstine Professor of the Study of Latin America) will explore their common theological ground.

“Video of scholars from vastly different fields of study talking with each other in an unscripted way, sometimes not having thought before about each other’s points of view, becomes almost an academic reality show — and that’s the vibe we are going for,” Goodman said.

The genesis of “PredictionX” goes back to 2008, when Goodman was on leave and serving as scholar-in-residence at the public television station WGBH in Boston. Annie Valva, who was then director of research and business development in the station’s interactive media department, encouraged Goodman to develop a potential broadcast and interactive set of materials that would put her scientific expertise to work.

Goodman initially came up with the idea of focusing on numerical simulations, perhaps a dry topic on paper, but one key to the understanding of crucial issues, and of how modern science is really carried out. One pressing reason was her concern about climate change.

“Explaining climate change calculations was my main motivation at first,” Goodman said. “When people hear scientists say ‘uncertainty’ in discussing climate change simulations, they often then dismiss predictions as uncertain enough to be dismissible and ignored. I wanted to explain that uncertainty is just a formal quantification of how sure scientists are of their forecasts, and that the level of certainty around climate is plenty high enough to be worried. In the fall of 2008, though, once the economy had collapsed and the swine flu epidemic had picked up, we decided that we needed to focus not just on climate, but on finance and epidemiology as well — since those are the other two fields where numerical forecasting has profound effects on our daily lives.”

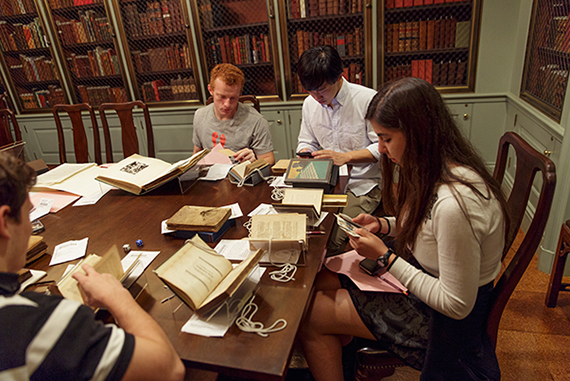

Valva and Howard Cutler ’68, a WGBH staffer, suggested working those ideas into a mini-series about the history of prediction. Though the concept didn’t get far past the planning stage, Goodman and Valva fortuitously wound up as Harvard colleagues. Now the associate director of instructional development for HarvardX, Valva saw that Goodman’s work lent itself to the same kind of multipart, interdisciplinary approach that was key to other HarvardX offerings, such as the recently launched set of short courses called “The Book: Histories Across Time and Space.”

“We started looking at Professor Goodman’s ‘Prediction’ project from a HarvardX point of view,” Valva said. Added Goodman, “It became more about the history of how humans have always tried to predict their own future. So that’s where the Mesopotamian sheep entrails came in.”

The three sections of “PredictionX” will be unveiled as they are completed. The first, “Omens and Oracles,” examines ancient methods of divination, including the Mesopotamian one named above — and no, that one isn’t recreated on video.

While that may seem barbaric to us, Goodman points out that a recognizable scientific method of inquiry started to emerge, with precise methods for divining, using animals’ organs.

More like this

Professor of Assyriology Piotr Steinkeller “is our expert on this, and it’s pretty remarkable how systematic haruspicy [divination by sheep’s livers] became. The diviners introduced the idea of a control sheep, and there was even a formal manual for divination by sheep liver created, where the meaning of every possible mutation — even those never observed — was discussed.”

This kind of evolution from “data to theory” in the story of haruspicy, Goodman suggests, points the way to the development of empirical methods in other fields, like astronomy. That leads into section two, which will cover the Scientific Revolution. As part of their research, Goodman and Lichtenstein will film interviews at Cambridge University, the Royal Society, the Royal Greenwich Observatory, and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in England in December. They’ll visit the historical site of the famous 1854 cholera outbreak in Soho, where physician John Snow did groundbreaking research and traced the epidemic to a contaminated water pump — even though that historical neighborhood is now being transformed by the building of a new shopping mall.

“Snow’s work is widely regarded as the earliest example of [predictive] epidemiology as it is practiced today,” Lichtenstein said.

The third section, due in about a year, will cover modern-day systems of prediction, including those for climate change, the global economy, genomic forecasting, and even the fate of the universe.

“PredictionX” is expected to have an online life far beyond its initial launch.

“My long-term hope is that HarvardX will be able to expand the range of predictive methods discussed in ‘PredictionX’ over time, with content generated by more and more faculty members,” Goodman said.

She expects to wrap up the project with an in-person symposium that will bring together prominent members of the Harvard community and guests; this would be streamed live and then archived.

The possibilities are many — and of course, unpredictable.