Photo by Kaitlin Buckley

Connecting Harvard history to its surroundings

Freshmen dive into archives to learn from University’s past about its ties to a wider world

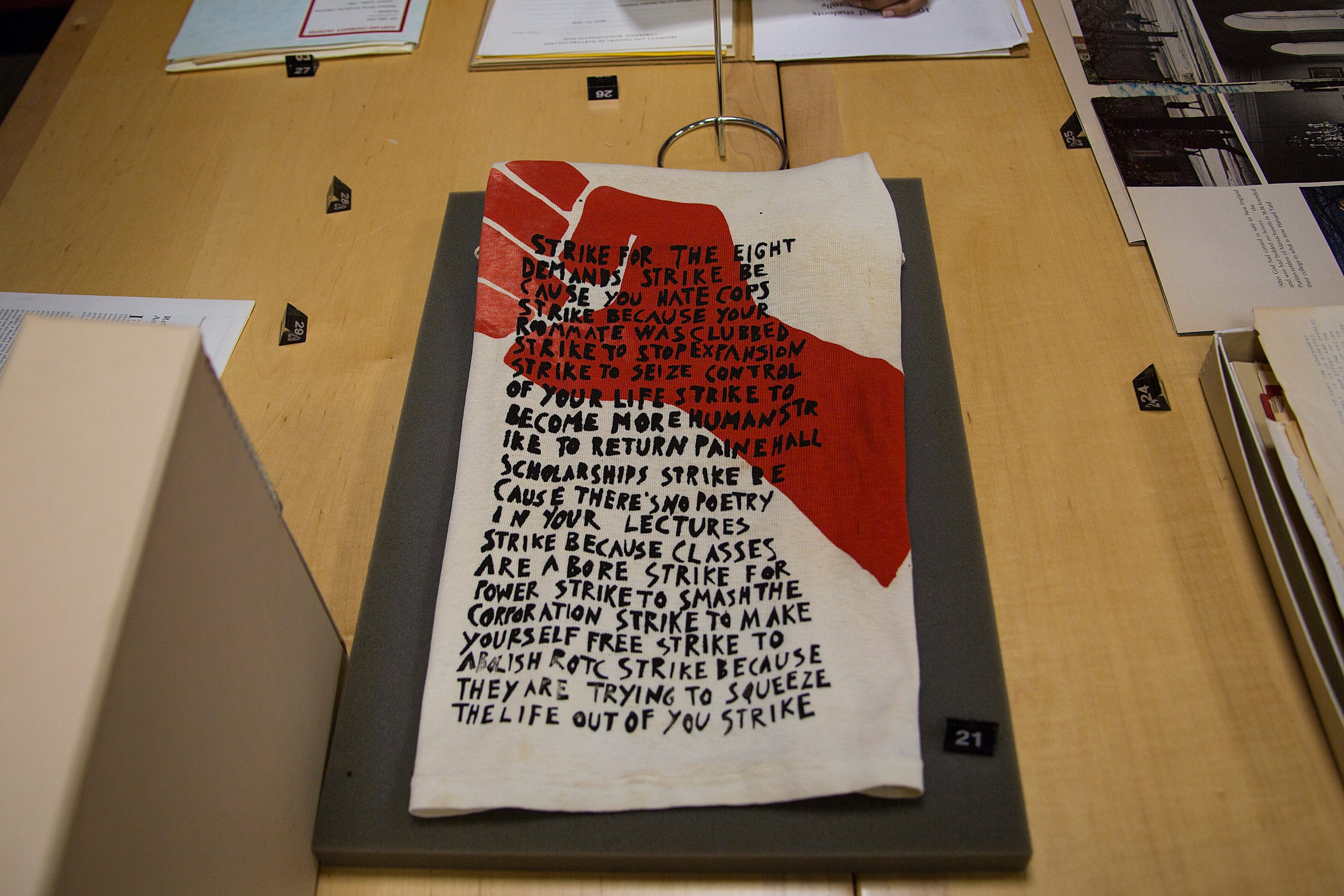

A cloth banner bearing a defiant red fist urges students to strike. An aged letter grants colonial troops permission to use Harvard Yard during the Revolutionary War and announces the accompanying campus relocation to Concord.

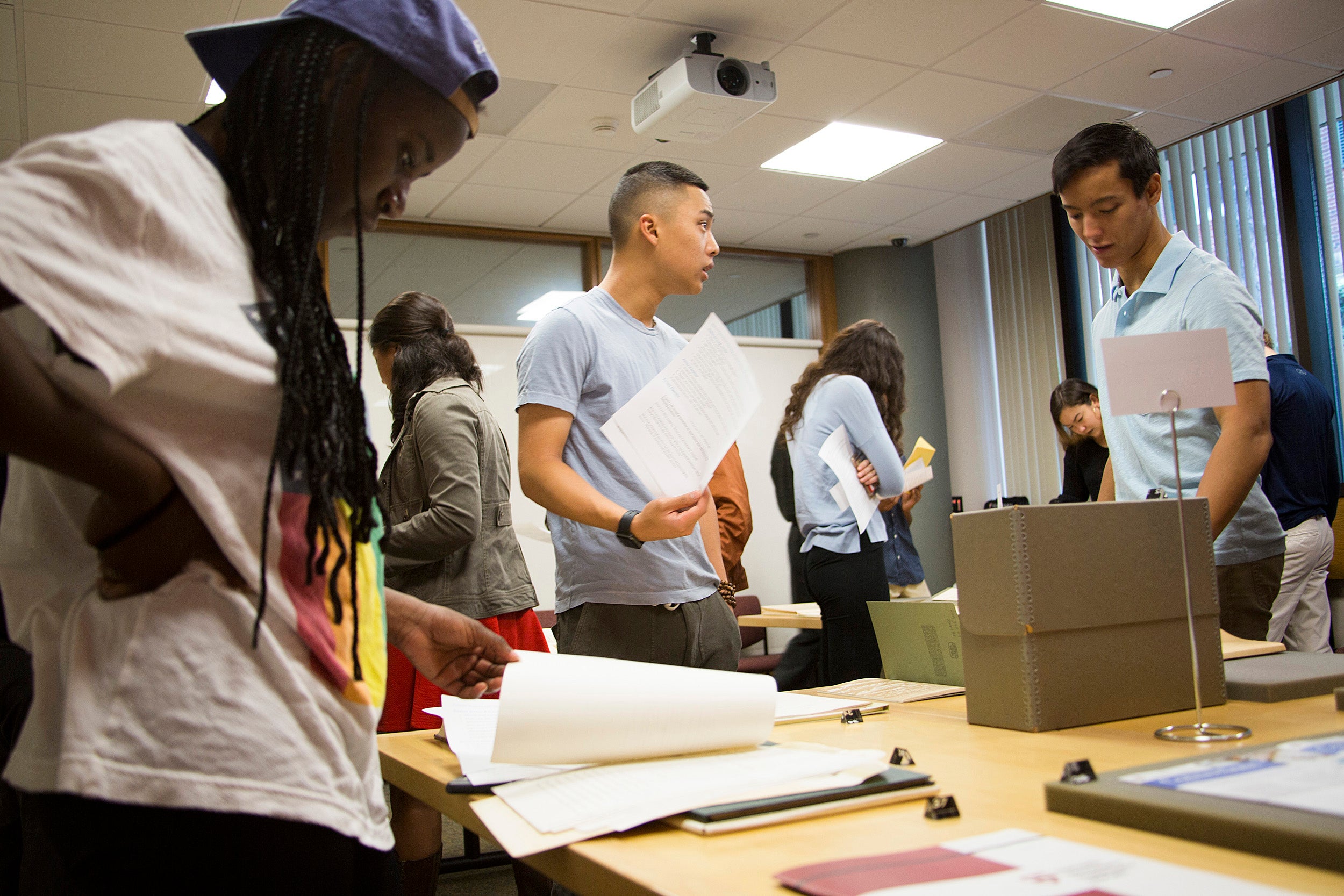

When students from Ariane Liazos’ expository writing class step into the Harvard University Archives — where they’re surrounded by stacks of private letters, Crimson articles, and protest buttons — they learn how many of the objects safeguarded at Harvard tell a story.

“They’ve never touched a letter that’s 100 years old and flipped through it,” said Liazos. “It makes them excited about history, seeing their connection to Harvard’s history on a deeper level.”

At the University Archives, librarians and archivists curate materials that show how students, administrators, community leaders, alumni, and staff reacted to the events of their time — such as the Vietnam War or apartheid in South Africa — and how they envisioned Harvard’s place in them.

Liazos’ course on “Class, Race and Space in Boston and Cambridge” raises questions about how physical spaces promote or detract from social interactions based on class and race. She brings her students to the archives so they can get a fresh look at history and explore Harvard’s impact on the community. In examining instances of students occupying University Hall in 1969 and Occupy Harvard in 2011, current freshmen are challenged to ask questions.

Liazos sees the partnership with the archives as essential. “The University Archives hold an amazing wealth of materials that enable me to introduce students to the process of historical research,” she said.

Emma Toh ’20 found part of Harvard’s past that surprised her. In 1930, Harvard laid off 20 women on the janitorial staff at Widener Library — called “scrubwomen” — when the Minimum Wage Commission from the Department of Labor determined that they deserved a raise. The ensuing discussion among administrators, students, alumni, and news media resonated as Toh began her project in 2016 during the Harvard dining workers’ strike.

A pin button from the Occupy Harvard protests bears a modified shield with “Veritas” replaced with “Occupy,” encircled by the Latin phrase “corruptio optimi pessima,” which translates to “the corruption of the best is the worst of all.”

Photo by Kaitlin Buckley

After Toh reached out to archives staff members, they presented her with boxes of material. “I started piecing the story together myself,” Toh said. “It was really challenging but much more rewarding.”

A scrapbook filled with newspaper articles from The Crimson and The Boston Globe, along with private correspondence and pamphlets, helped illuminate the controversy from different angles. Eventually, the janitorial women were rehired at minimum wage.

Librarians Susan Gilroy and Barbara Meloni “went above and beyond — directed me and showed me how to do things,” said Toh. Without visiting the archives, Toh said, she wouldn’t have been able to understand the depth of these primary sources. Since much of Harvard’s enormous archival material is not yet digitized, an in-person visit is the only way to get close to them.

The archivists help student researchers by showing them how to search the online catalog to find primary sources relevant to their topics, then how to evaluate and interpret them.

“My favorite part is watching the students make historical connections to current events and seeing how excited they are about the process,” said Meloni.

Students can delve into any subject that interests them, such as social movements on campus, community engagement in Allston, or Harvard’s relationship with Cambridge’s working class. Visits to the Cambridge Historical Society and the North End Historical Society take the students out of the Yard to learn about urban development through another historical lens.

Image 1: Peyton Dunham (from left), Lion Lee, and Franklin Civantos examine sources from the Archives as part of Professor Ariane Liazos’s freshman expository writing class. Images 2: Katie Okumu (from left), Veronica Santana, and Lainey Newman explore materials from student demonstrations on campus in the 1960s and 1970s.

Photos by Kaitlin Buckley

As part of their final project, the students present their research to community representatives at an event hosted by the Mindich Program for Engaged Scholarship. They discuss their work with the Cambridge Historical Society, the North End Historical Society, Health Leads at Massachusetts General Hospital, MIT’s Community Innovators Lab, and the Allston Brighton Community Development Corporation, fielding questions about their findings. The students focus on thinking critically about the different sides to each conflict and prepare to defend their arguments, while opening their minds to other points of view.

“It’s like doing a jigsaw puzzle,” Toh said. “There’s a freedom to explore what you want to explore.”