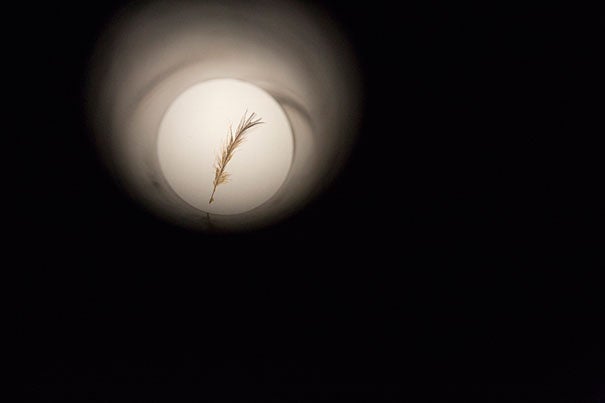

A fading image of a tiger is part of the Harvard Museum of Natural History’s exhibit on extinction, “Next of Kin: Seeing Extinction through the Artist’s Lens.” Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Video: Editor Joe Sherman; cinematographers Joe Sherman and Kai-Jae Wang/Harvard Staff

Drawing the eye to extinction

Artist’s perspective gives HMNH exhibit ‘gut level’ power

As you watch, the jaguar fades to black. Also the monkey next to it, the antelope, the grizzly bear, the wild dog, the Siberian tiger.

Look around the darkened room and you’ll find other animals fading or already gone: the heath hen, extinct in 1932; the great auk, last seen in 1844; and New Zealand’s flightless moa, which survived only a few hundred years after humanity’s arrival just before 1300.

The specimens of threatened, endangered, and extinct species — all from the collections of the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ) — are part of a new exhibit at the Harvard Museum of Natural History (HMNH).

“Next of Kin: Seeing Extinction through the Artist’s Lens,” was created by visual artist Christina Seely in collaboration with the Canary Project, which produces art and media on ecological issues. Supported by a gift from 1968 Harvard Business School graduate Clark Bernard and Susana Bernard, Seely drew from the MCZ’s vast collections, which encompass some 21 million specimens, including many species considered threatened, endangered, or extinct. The exhibit runs through June 4.

Jane Pickering, executive director of the Harvard Museums of Science and Culture, of which the HMNH is part, said during a reception last month that the exhibit is a departure for the museum, which typically features scientists’ views of scientific topics.

“This is something that’s a bit different, a bit of an experiment, and not all experiments work,” Pickering said. “I think in this case it really did.”

Species extinction and reductions in biodiversity have been increasing rapidly over the last two centuries. It remains to be seen whether today’s human-driven crisis will rival past global mass extinctions, as some have warned, but the trends are worrisome, said MCZ director James Hanken, the Alexander Agassiz Professor of Zoology.

“The rate at which species are being lost today is extremely high and much higher than 100 years ago, 200 years ago,” Hanken said. “If things continue unabated, the world, including the U.S., will be very different in 150 years from what we see around us today.”

When the MCZ was founded in 1859, Hanken said, few scientists were concerned about extinction and biodiversity loss. Now most are, and part of the museum’s mission is to educate the public and policymakers on urgent scientific issues. An artist’s perspective helps the museum accomplish that goal, Hanken said.

“Scientists go about it [education] with charts and graphs and hard facts,” he said. “It’s not terribly effective, not enough to change the [public] consciousness. Artists have a different way to approach a problem. They appeal on a gut level, an emotional level.”

Seely became interested in extinction during a trip to photograph animals in the Arctic. A year ago, after a conversation with Pickering, she began working with faculty-curators of the MCZ’s mammal and bird collections to identify specimens to include in the exhibit, which opened a week before Christmas.

A visitor sees clear display cases lit to stand out in the darkness. One holds brown boxes of great auk bones — a box of skulls, a box of ribs, a box of spines — reflecting the bird’s onetime abundance across the North Atlantic. Nearby a single heath hen egg lies in a large bed of white cotton, which Seely said shows the care with which eggs are packed away in the collection. The last heath hen was a male on Martha’s Vineyard.

Another eye-catching display features several large photographs of endangered or threatened animals. Arranged along two walls, the images, like the creatures themselves, fade from view as a visitor watches. The exhibit also includes the ear of a sei whale, a narwhal tusk, and the moa.

Seely said she’s hoping an artist’s touch might help spread awareness on important scientific topics. “I’m interested in figuring out ways to get the general public connected in a deeper way to what’s happening.”