Thomas Patterson, Bradlee Professor of Government and the Press at Harvard Kennedy School, offered some thoughts on a newly released analysis of the journalism surrounding the 2016 presidential campaign.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The making of the campaign, 2016

Media coverage of candidates was unbalanced early and often, study says

Of all the factors that make the 2016 presidential election one for the history books, one of the most fiercely debated ones involves the degree to which the mainstream media coverage may have shaped the outcome of the Democratic and Republican primaries.

Much attention has been given to the theory that Donald Trump, a celebrity businessman with no prior political experience, was propelled to the top of a vast Republican field because he received unending, unprecedented media coverage and was able to dominate the daily news cycle from the moment he entered the race by making sensational statements, which effectively pushed his 16 opponents out of the spotlight.

Is there merit to the perception about the quantity and quality of media attention of the top candidates on both sides: that journalists went easy on Trump because he was good for ratings and clicks; that Sen. Bernie Sanders was ignored early on but later got little of the negative scrutiny that Hillary Clinton did; or that the press corps fixated on Clinton’s so-called “scandals,” not her positions, and held her to a harsher standard than it did male candidates?

In short, yes, according to an analysis released Monday of mainstream print and television content in 2015 during the crucial period preceding the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary, known as the “invisible primary,” by Thomas E. Patterson of the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS). Both events traditionally mark the formal start of each presidential race.

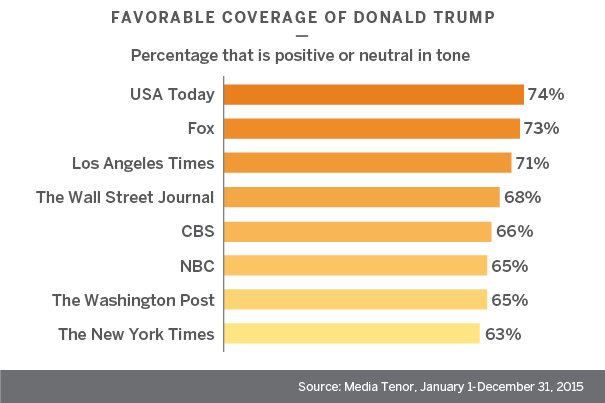

Using data from eight news outlets — CBS, Fox, NBC, the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, USA Today, the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post — Patterson and his team evaluated both the quantity and the positive or negative tone of reports about candidates and found:

- The Democratic race got less than half the coverage that the Republican race received.

- Trump got the most coverage of any candidate running on either side, the vast majority of which was favorable in tone, despite claims that his rise was mostly driven by cable TV and social media.

- Sanders supporters were right: He didn’t receive much attention in the first half of 2015. Clinton got three times more coverage, and even Trump, Jeb Bush, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and Ben Carson each got more than Sanders. But once he did get coverage, the attention was far more positive than it was for Clinton. In fact, Sanders received the most favorable coverage of any Democrat or Republican running, collecting three positive pieces for every negative one.

- Meanwhile, the study said that the press distrust of Clinton is demonstrable. She received the least favorable coverage of any Democratic or Republican candidate. In the first half of 2015, there were three negative reports about her for every positive one. In the second half, the ratio was 3:2 negative to positive. Fox led the way, broadcasting 291 negative reports about Clinton and just 39 positive ones. In contrast, Fox gave Sanders 79 positive mentions and 31 negative ones.

In an interview, Patterson, the Bradlee Professor of Government and the Press and interim director of the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at HKS, spoke with the Gazette about the findings.

GAZETTE: What prompted this analysis, and what for you was most surprising?

PATTERSON: We’ve done this in some of the past presidential elections. We did it in 2000, we did it in 2008, and we did it a little bit in 2004. It’s one area where we’ve sometimes tried to make a contribution to understanding what’s going on in the media coverage.

Given all of the attention that was devoted to Trump by the press, it certainly wasn’t surprising that he got the lion’s share of the coverage. The interesting part is how much of that was favorable coverage, which contradicts the media narrative that they were tough on him from the beginning. They gave him a pretty good ride in the early going, not only in terms of how much coverage they gave him. It’s pretty unusual to give heavy coverage to someone at the bottom of the polls.

It wasn’t all that surprising to see the negative coverage on Hillary Clinton’s side, although the degree of the negativity was a bit of a surprise for us. And how much of the press was what we would put in the “bad press” category. The press normally covers the horse race, not so much the issues. In her case, her issues got twice the coverage of the other candidates and it was largely negative. So I think the press certainly contributed to the rise of Donald Trump and the struggle that Clinton has with her unfavorability ratings.

GAZETTE: Why was the Trump coverage so favorable and voluminous given the controversial and even incendiary nature of many of his early public remarks? And why didn’t Jeb Bush, who had a massive war chest, a campaign operation, name recognition, and status as the frontrunner, get similar positive attention?

PATTERSON: I think there are two explanations for Trump’s favorable coverage that also help explain Bush’s unfavorable coverage. One is they tend to embed their narrative in the horse race, and if you’re a candidate like Trump who’s rising in the polls, the press tends to treat that in a favorable [way]. So much of what’s said about the candidates is where they are in the horse race. And as a rising candidate, in every case we’ve ever looked at, that’s always accompanied by favorable coverage. It’s O.K. to be the frontrunner if you can stay there, but the minute you start to drop, the narrative becomes “what’s wrong with this candidate; why is this candidate losing ground,” and that’s a negative story.

The other thing with Trump: We were for the most part looking at the traditional press, and they pursue what’s sometimes called the “objective model,” or “balance.” So if they quote someone attacking Trump, they have a tendency to [also] quote someone who’s saying good things about Trump. So if he’s going to get attacked by someone about his stance on building a wall, their model says you go out and find somebody who’s going to say something nice about that.

GAZETTE: While the media’s horse race preoccupation and taste for what’s good copy rather than what’s helpful for voters was similar for both parties, you say the coverage of the Democratic race was “markedly different” than the Republican contest. How so?

PATTERSON: It got much less attention than the Republican race. I think the press really was preoccupied in many ways with what was going on on the Republican side, maybe because they thought there was greater uncertainty about how it was going to come out.

GAZETTE: So it was not primarily a function of having a 17-person field?

PATTERSON: That plays into it. The Republican debates started earlier, and the debates triggered a lot of the coverage, so there were a number of factors that played into it. I just think they thought that was going to be the race, [and] on the Democratic side, it was going to be Clinton from the beginning, so that got underplayed. After Bernie Sanders started to move upward in the polls and Clinton started to decline and something that looked like a horse race was beginning to emerge, then you saw an increase in coverage. But even then, most of the attention was on the Republican side.

The other difference is, by far, Hillary Clinton received the most negative coverage of any of the candidates, Republican or Democratic, as a percentage of her coverage.

GAZETTE: Why didn’t Sanders get the kind of early press boost that Trump got, given that both started as underdogs who unexpectedly drew large crowds?

PATTERSON: It took a while. After he started to campaign, it took him a while to draw those large crowds and start moving up in the polls. Whereas in Trump’s case, there wasn’t that much of a time lag between his announcement and then making some of the statements that drew a lot of attention. Bernie was sounding like Bernie, so once you told ‘the Bernie story,” there wasn’t necessarily a lot of fresh news coming out of his mouth, while Trump was saying something pretty new and sensational every day. Once they thought, “Could there be a real race here?” then he started to get more attention. As he rose in the polls, it was as positive a story for Bernie as it was for Trump.

His issue coverage was very positive, more positive than any of the other candidates, in part because there weren’t a lot of attacks on him coming from journalists. Even Hillary Clinton wasn’t attacking his positions on student loans and the minimum wage and economic fairness. They were part of her platform, too — not in the same way, but it wasn’t at odds with anything she was saying fundamentally — so you didn’t have that attack/counterattack dynamic going on. And then there’s always a little bit of that David and Goliath story whenever you have someone like a Sanders coming at a frontrunner who’s got lots of money, lots of endorsements, thought to be the presumptive nominee almost from the start, then that becomes part of the narrative too.

GAZETTE: The paper debunks some popular notions about the coverage in 2015: that the media establishment didn’t boost Donald Trump’s early candidacy because it was mostly negative, or that the excessive and uncritical coverage was a phenomenon of cable TV only; that Bernie Sanders was consistently ignored and treated unfairly because the media favored Hillary; that Hillary wasn’t held to a different and higher standard than her male rivals. What did you find?

PATTERSON: The traditional press was operating out of news values, as they always do. The press always has an appetite for the sensational, the outrageous. That always beats the ordinary. [Trump] was a colorful story, and the mainstream press is susceptible to that. That’s so ingrained in the model, so when he was saying those things, it was front-page news everywhere. It wasn’t just on Fox. They were very much part of the Trump boost.

In terms of Clinton, they’ve always had a terrific appetite for scandal. It doesn’t have to be proven, it just has to be in the air. So the [State Department] emails and Benghazi chewed up a lot of Hillary’s coverage. Those were big stories. If you’ve got a touch of scandal around you and you’re way at the bottom of the polls, they don’t much care about that. But if you’re the frontrunner and those things are clearly driving up your unfavorable ratings, chewing away at your poll standing, that all feeds into the horse race narrative and you have a nice merging of the “scandal stream” and the “horse race stream.” Both are irresistible, and when they combine, it becomes doubly so.

Sanders was treated like virtually every other candidate who’s at the bottom of the pack. They always struggle for press recognition. He was not singled out in that sense. He was the norm. Trump was the outlier on that variable. Bernie got a pretty good ride after they started to pay attention to him. He increasingly got the news attention he was looking for. It was favorable on the horse race dimension, and then of all the candidates, his issue coverage was the most favorable. One can argue exactly why that was the case, but a large part of it was that at that point, no one was attacking him on those issue positions. Without a conflict, the press is going to pretty much go with what he’s saying on the issues. He’s going to be able to define his candidacy without a counter voice coming into the mix.

GAZETTE: Why is the political media’s self-assessment seemingly so at odds with your findings? And what should they do better to guard against inadvertently or inappropriately putting their thumb on the scale to help or hurt a particular candidate in the future?

PATTERSON: I think journalists are so trapped in the horse race narrative they don’t recognize the degree to which it drives both the volume and tone of the coverage. When they do have a little more discretion or when they do step back a little bit, they might be more critical of a candidacy like Trump’s. It’s those exceptional moments that stick in their minds: “Well, in October we said this about the danger he posed on this particular issue.” But what they’re missing is the day-to-day narrative they’re creating by being so tightly focused on the candidate’s standing in the race. They’re just not seeing the forest; they pick out the tree that’s pretty favorable to their argument. They do write stories of that type, but it’s overwhelmed by the day-to-day headline story about the candidate on the rise and the issues that are driving that rise, and the like.

I think the press over the last half-century has become increasingly fixated on inside baseball and the political game. As long as they’re in that frame, you’re going to get this kind of coverage. They’ve got to step out and cast their vision more widely and think about elections. Elections are about voters as well as about candidates. They’re about the condition of the country as well as whatever the campaign organizations might be doing. They just have to broaden their lens. Once they broaden their lens, then you start to bring in other elements of the campaign in a fuller way and you diminish, to some degree, this driving narrative around the race.

[There’s] an assumption that that’s what the audience is looking for, they really are interested in following the race as a race. The other reason is: It’s easy journalism. It was very interesting that it took them a couple of months to say “Who are these Trump voters?” They were focused on “The Donald” and what the pollsters were showing. They weren’t all that interested in why this guy is resonating, what the people who are backing him thinking about? Those stories could’ve come much earlier. But you can’t find those stories if you don’t go looking for them.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.