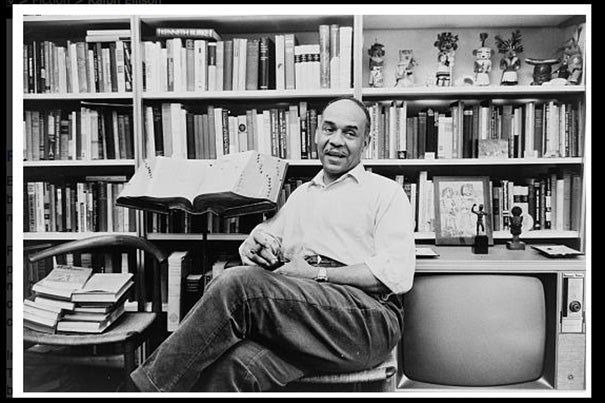

Novelist Ralph Ellison was a panelist at a Harvard conference on the novel in 1953, just months after “Invisible Man” gave him lifetime literary visibility. Newly discovered audio from the event provides a rare early glimpse of an extemporaneously incisive Ellison, who went on to make a living as a teacher and literary journalist.

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Lost voices of 1953

The thoughts and theories of writer Ralph Ellison come to life with rediscovery of Harvard conference recordings

Staffers at the Woodberry Poetry Room made a startling discovery earlier this year: audio recordings of long-forgotten literary voices from a 1953 Harvard conference on the contemporary novel. Among them is Ralph Ellison, who just months earlier had won the National Book Award for his first novel, “Invisible Man.”

“Lightning struck me,” he wrote later of the prize, “leaving me standing amazed.”

There were other lightning strikes in 1953, including the invitation to the Harvard Summer School conference. During the intense sessions on craft and criticism — some of which will soon be available as digitized audio — the voice of a gifted teacher rose. (Ellison, a fervent reader who never finished his second novel, much less a college degree, went on to earn a living as a professor and literary journalist.)

Soundbytes: Ralph Ellison on a writer’s role

Ellison emerges on the recently digitized recordings as a gifted critic who is thoughtful, precise, and funny — often the lone voice on panels to bring the conversation back down to earth when it strays into the abstract. He was also aware of being the only black man at the conference. “This doggone integration thing,” he joked to a friend about the Harvard gathering, “maybe is going too fast.”

But Ellison was unafraid. In one session he dressed down the Irish novelist, poet, and critic Frank O’Connor, who was then teaching a Summer School course, saying O’Connor was being too flip in discussing the novel. The form needed updating, agreed Ellison, since it was stuck between the mannerly and the hard-boiled. But it was still a powerful instrument for executing the writer’s “moral role.” Such give-and-take among literary stars drew attentive audiences. As many as “a grand of people” at once, Ellison wrote in the Aug. 6 letter, attended conference events, including one in Sanders Theatre.

His novel began, famously, with the line “I am an invisible man.” Its narrator lives in a burrow-like basement on the edge of Harlem, though it is “warm and full of light. Yes, full of light.” The novel, part language experiment on the diversity of American slang, begins and ends underground — territories of invisibility that the author himself could no longer enjoy (or endure) after winning the National Book Award. He had become famous.

Soundbytes: Ralph Ellison on the novelist’s ‘delight’

In early January, when news of the award came, Ellison was 39 and living in New York. He was a native of Oklahoma City, a Tuskegee Institute dropout, a sometime musician and writer, and a wartime veteran of the U.S. Merchant Marine, in which he had served as a cook. Winning the award flung him from obscurity into a madcap year of interviews, televised panels, lectures, and speeches. “I can’t help but feel,” he wrote, “that some mistake was made somewhere.”

At the award ceremony on Jan. 27, Ellison got a full measure of introductions to America’s writing elite. He shook hands with Langston Hughes, William Carlos Williams, Eudora Welty, Rachel Carson, and — near the bar at the reception — William Faulkner, a huge literary influence on Ellison. Sharing prizes with him that year were Bernard DeVoto (for nonfiction) and Archibald MacLeish (for poetry), Harvard men who had earlier posed with the newcomer in a chummy Library of Congress portrait. “Nothing stuffed shirt about them,” Ellison wrote to a friend.

The sharpest pang of unreality probably came from the competition he bested to win the award, Ernest Hemingway for “The Old Man and the Sea” and John Steinbeck for “East of Eden.” “They were the real writers,” Ellison said later. “I was just an upstart.”

A Harvard ‘homecoming’

But arriving at Harvard that August for the first time, Ellison wrote afterwards, felt like a homecoming. Harvard was where his namesake (Ralph Ellison’s middle name was Waldo), Ralph Waldo Emerson, a century before had been a leading intellectual light for whom consciousness was paramount. The black writer sensed a kinship. “If others saw him as merely a Negro author,” wrote one biographer, “Ralph possessed a far more acute sense of association.” Ellison wrote after the conference, “If we ever have a boy, Harvard will be his college.”

An epiphany he had at Harvard — researched by Poetry Room staff — deepened his emotional ties to the University. On the evening of Aug. 3, the first day of the conference, Ellison finished an after-dinner session on the novel at Sanders Theatre in Memorial Hall. He stepped into the building’s transept, lined with marble tablets identifying Harvard’s Union dead from the Civil War. Ellison felt an immediate “shock of recognition,” he said later in a 1974 Harvard Commencement address, a moment of anguish at his own forgetfulness, ingratitude, and indifference about the sacrifices in the war to end slavery. No history had ever set the same deep hook of feeling in him that the solemn tablets had, said a chastened Ellison. “I knew that I stood within the presence of Harvard men who had given their young lives to set me free.”

Joining Ellison and O’Connor at conference events were scholars, literary critics, and writers: the French poet Pierre Emmanuel; the Belgian novelist Georges Simenon, then living in Connecticut; and by some accounts the American fiction writer and literary journalist Katherine Anne Porter.

The critics taking part included Carvel Collins, who in 1942, while teaching at Harvard, offered the first university course devoted to Faulkner. Panelist Stanley Edgar Hyman was a critical theorist and New Yorker staff writer who helped Ellison get “Invisible Man” published. Andrew Nelson Lytle, a pivotal member of the Southern Agrarians literary movement, was a panelist. So was Harvard professor W. M. Frohock, the author of a book on violence in the American novel. The German poet and literary critic Hans Egon Holthusen represented another kind of anomalous minority at the Harvard conference. He had been a member of both the S.S. and the Nazi Party. But he knew his post-war literature.

“Up here,” wrote Ellison of the company he kept at the conference, “you have to be pretty nimble.”

Forgotten voices found

Finding the lost audio was nimble work, too. “I came across the conference in HOLLIS,” which searches the Harvard Library database, said Poetry Room curator Christina Davis. From there, she uncovered six reels of tape, 12 hours of listening. She had been searching for historic recordings to digitize — 100 cassettes worth — thanks to a $19,000 grant from Harvard College Library.

Davis, a poet and a champion of oral history, said that finding Ellison on tape promised to be a rare instance of his recorded voice in the midst of formative discussions, not just reading or lecturing. It was not a poet’s voice, she added, but it was too compelling for the Poetry Room to ignore — especially since 1953 “was a pivotal year in his existence and that of the nation.” (A month after the conference the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to rehear the landmark desegregation case now known as Brown v. Board of Education.)

The audio covers just two days of the conference, Aug. 3 and 4. Once they are digitized, divided into tracks, and uploaded to the Poetry Room website, the recordings will be made available online, as early as this fall.

Davis believes the recording is also a valuable artifact illustrating how American speech has been flattened and homogenized by the ubiquity of television and radio, media that favor clear, Midwestern accents over other regional inflections. (On one panel, Collins talked about “high-larious” moments in Faulkner. Ellison’s voice, mellifluous and precise, sounds like a radio-era Jack Benny.) “The very instrument,” recording technology, that saved “period accents” for posterity, she said, also had a role in taming or even eliminating them.

In addition, the conference constituted a sort of super-seminar on the state of the American novel six decades ago. In the sessions, she said, “You can hear thought happening.”

A novelist teaching

For Ellison, said Davis, part of that thought process was a knack for synthesizing the many strands of a discussion. He was appealing to the Cambridge audiences as a man who was both orderly and daring — while unafraid to be funny.

“I’m very interested in [audience] reception,” said Davis, who oversees thousands of collected recordings. “At the Poetry Room, we always listen for laughter,” and there was plenty at the conference. “The audience,” added Poetry Room staffer Mary W. Graham, who listened to all 12 hours of tape, “is not too stiff.”

One audience member that summer was a young Harvard professor of government named Henry Kissinger, then the editor of the journal Confluence: An International Forum. Soon after the conference, he asked Ellison for an essay on race, creativity, and literary consciousness. The author dusted off an unpublished 1946 piece, which Kissinger published that December as “20th Century Fiction and the Black Mask of Humanity.”

Letters indicate that Ellison prepared a 30-minute lecture on the America novel, which he predicted to a friend would be “thirty of the damnedest minutes I ever spent.” The lecture is not among the trove of recovered audio, and was never published. But its echo, and echoes from the conference, survive in a 1957 essay called “Society, Morality, and the Novel.” His same obsessions from 1953 abide there, including the centrality of Mark Twain, Herman Melville, Faulkner, and Henry James.

Surviving too is Ellison’s sense that a writer’s place is at the typewriter, not on the picket line, an observer’s attitude that a decade later got him in trouble with some other blacks during the Civil Rights Movement.

“I don’t think that’s a writer’s business at all,” snapped Ellison at the conference, when asked about fiction as a means for protest or prescription. “His business, of course, is to write.”