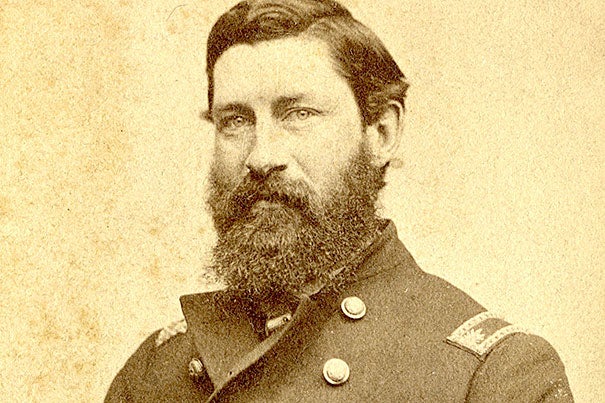

An intimate look at Zabdiel Boylston Adams, an 1853 graduate of Harvard Medical School, was shared by his great-grandson Mitchell L. Adams. Zabdiel Boylston Adams labored in surgeries at Gettysburg — staying up for two days and three nights — recounted the younger Adams.

Image courtesy of Countway Library of Medicine/Harvard Medical School

Saga of a Civil War surgeon

Lecture recalls Harvard physician who also served in the infantry

There are 2,000 plaques and other memorials on what was once the Civil War battlefield in Gettysburg, Pa. Only one is dedicated to a physician, Zabdiel Boylston Adams, an 1853 graduate of Harvard Medical School.

The story of Adams, including his famous Boston lineage, Civil War service, and postwar practice, was recently told at the Countway Library of Medicine, part of a series of lectures on medicine during the murderous national conflict 150 years ago.

“He jumped right in,” said Mitchell L. Adams ’66, M.B.A. ’69, of his great-grandfather’s service, “and was in it from the beginning to Appomattox,” when Southern forces surrendered.

Mitchell Adams, who delivered the lecture, is a former member of Harvard’s Board of Overseers and recently retired after 10 years as executive director of the Massachusetts Technology Collaborative.

Along with many other tales, he told of his ancestor’s Gettysburg experience. On the afternoon of July 2, 1863, the doctor set up a rude field hospital close to the line of battle. (One flat rock that was used as a surgical table is still there.) Adams had noticed how many soldiers were dying during transport from combat to distant medical care. Because he began treating patients so quickly and near the fighting, the 1895 plaque reads, “many of our wounded escaped capture or death.”

For Adams (1829-1902), as for his American generation, the Civil War was life’s most defining period, which not only recorded stories of bravery but also opened postwar lives to heightened inspection. Countway is home to the Zabdiel Adams papers, ranging from battlefield letters, maps, and diaries to documents that illuminate later medical practice.

An advocate for vaccination

Nuggets abound. For instance, Adams was an ardent advocate for vaccination, inspired in part by his prewar experience as a surgeon aboard an immigrant ship. During the war Adams was not a champion of hasty amputations, but argued for excision and other limb-saving measures. And he describes the everyday pressures of a country practice in Framingham, Mass.

But the Civil War — with its 750,000 dead, its slaughterhouse battles, and its crude medicine — was at the center of the Feb. 7 lecture.

Adams, his great-grandson recounted, labored so long in surgeries at Gettysburg — up for two days and three nights — that he was blind with exhaustion. Twice wounded, he fought hard to get back into the service when mustered out. By 1864, Adams resorted to an unusual ploy to extend his service. He gave up battlefield medicine and rejoined the army as an infantry officer.

As delivered by the present-day Adams, “Dr. Zabdiel Boylston Adams: Surgeon and Soldier for the Union” was breezy and dramatic. It placed the doctor in the context of his two originating families, Boylston and Adams, both woven tightly into the history of early America. It recounted a modest, quiet postwar medical practice. But it also leapt fully into the action of the war as the doctor witnessed it.

The lecture was the second in the Medicine and the Civil War Series, co-sponsored by Harvard’s Center for the History of Medicine and the Office for Diversity Inclusion and Community Partnership. The lectures are paired with “Battle-Scarred,” an online exhibit.

Adams was an ardent abolitionist, and to him a war to end slavery was a “high and worthy and holy” goal, his great-grandson said. The same day Bostonians learned of the Southern attack on Fort Sumter, Adams left his lively city medical practice and reported to the State House to volunteer. Pictures of the time show a young man in uniform, robust and full-bearded.

Adams enlisted as an assistant surgeon with the 7th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry and was with the 32nd Massachusetts at Gettysburg. As an infantry officer in 1864, he was severely wounded at the Battle of the Wilderness and captured by Confederate forces. His left leg shattered, he lingered untreated for weeks. Gangrene set in, but Adams treated himself by pouring pure nitric acid into the wound, “although the pain,” he wrote later, “was almost unendurable.”

His wartime experience was Gump-like and broad. He was within earshot of the First Battle of Bull Run, reporting there the next day on an ambulance wagon. He took part in many iconic battles, from the Peninsular Campaign to Second Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, and, by 1865, the siege of Petersburg, Va., that ended the war.

Along the way, said his great-grandson, Adams was a witness to the social history of the time. Entering the unguarded grounds of the White House one day, he saw President Abraham Lincoln reading on a White House porch, his chair tipped against a wall. A touch of the Boston patrician emerged then, when Adams disparaged the unkempt kitchen garden and wondered out loud when the first family would take in boarders.

An early role for Harvard

Of course, Harvard is part of the Adams story. In 1845, he enrolled at the College his ancestors had peopled since the 17th century, but after two years he was “rusticated” — expelled — over a prank. Adams graduated from Bowdoin College in 1849, then entered Harvard Medical School and spent a year training in Paris.

There were four men in the family with his name, and three were doctors, including his father. “My earliest memories are associated with medical life and practice,” Adams wrote in an 1894 memoir. (The typescript is at Countway.) Even his Sunday school teacher, a Harvard medical student, added inspiration — lecturing his young charges on human anatomy and, as Adams wrote, “the wonders of God as shown in the mechanism of sight and hearing.”

As a freshman at Harvard, Adams discovered the wonders of ether. He watched as his roommate in 3 Hollis Hall “inhaled it for fun.”

Medical wonders came toward the end of his life too. In 1900, Adams helped Framingham Hospital to acquire its first X-ray machine. He quickly directed the diagnostic beam on his own left leg, where for decades he swore there was still a Civil War bullet lodged. (There wasn’t.)

At a first-floor reception following the lecture, the great-grandson — a lean, precise man who favors bow ties — mingled with listeners. At a table nearby were examples from the Adams papers. Also on display were the shoulder boards of a major that Adams wore on his army uniform, his ophthalmoscope, and a sunlike genealogy chart, with generations of Adams men radiating from forebear “Henry Adams” (1583-1646) at the center. There was a velvet-lined field surgery kit like the one Adams would have used, including a glittering bone saw.

A picture of the doctor taken not long before his death in 1902 showed him shrunken and with a dapper shovel beard, all gray. He wore a look that combined the remains of war: amusement, pain, and wisdom.

The great-grandson had ended his lecture with his ancestor’s penultimate reflection. “War is for beasts,” he said. “There should never be another on Earth.”