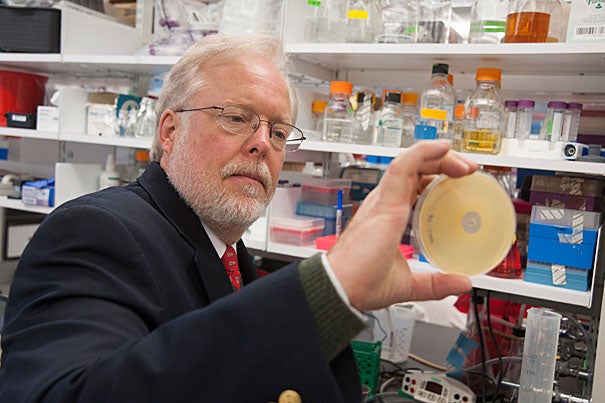

Michael Gilmore, who organized the Harvard-wide Program on Antibiotic Resistance and whose lab in May announced it had decoded the genome of the 12 known VRSA strains in the United States, said the group is taking a diversified approach to meet the challenge of antibiotic resistance.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Battling a bacterial threat

Researchers join forces, explore strategies against drug-resistant bugs

In 2002, a new kind of bacterial infection was detected in the United States. It was caused by a common bug, Staphylococcus aureus, but with a troubling new twist. It was resistant to the drug that typically offered the last line of treatment, when other remedies failed.

The appearance of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, dubbed VRSA, sent shock waves through the medical and public health communities. For years, vancomycin was the physicians’ ace in the hole, used to treat infections that didn’t respond to other drugs, in particular methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, known as MRSA.

In 2009, Harvard scientists teamed up to tackle the challenge posed by growing antibiotic resistance, creating a program bringing together researchers to examine the problem of antibiotic resistance, with a specific focus on VRSA, MRSA, and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus, or VRE.

Michael Gilmore, who organized the Harvard-wide Program on Antibiotic Resistance and whose lab in May announced it had decoded the genome of the 12 known VRSA strains in the United States, said the group is taking a diversified approach to meet the challenge of antibiotic resistance.

The group has seven main investigators who communicate and meet regularly, sharing notes and brainstorming fresh approaches to combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Members of the group include Gilmore, the Sir William Osler Professor of Ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary; Richard Losick, the Maria Moors Cabot Professor of Biology in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS); Fred Ausubel, professor of genetics at HMS and Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH); Eleftherios Mylonakis, formerly at MGH and now contributing from Brown University; Suzanne Walker, professor of microbiology and immunobiology at HMS and an affiliate of the FAS Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology; Roberto Kolter, professor of microbiology and immunobiology at HMS; and David Hooper, professor of medicine at HMS and MGH.

Of the three bacteria types the group is studying, MRSA is the most widespread, making up 30 percent of bacterial infections contracted outside of hospitals. It is deadly, having killed 18,000 per year since 2005, and is resistant to all of the commonly used antibiotics, including penicillin, amoxicillin, and methicillin. Vancomycin is typically reserved to fight MRSA and has to be carefully administered in a hospital, Gilmore said.

One difficulty in fighting antibiotic resistance is that the pace of new drug discovery has slowed, and so new drugs to which bacteria could not yet be resistant are few, Gilmore said. Antibiotics are often isolated from new strains of bacteria taken from the environment. The problem, Gilmore said, is that pharmaceutical companies have already scoured the easily accessible locations and are now extending into extreme environments in search of novel compounds.

These compounds are often the result of the chemical warfare that bacteria wage on each other. But only about 1 percent of bacteria found in the wild can be grown in the lab, Gilmore said, making the other 99 percent too difficult to use as sources of new medicines. Though efforts are under way to create strains that can live in the lab — or to transplant their DNA into bacteria like E. coli that grow readily in laboratory conditions — the process remains slow and difficult, Gilmore said.

The problems in dealing with drug-resistant bacterial strains aren’t just biological, however. Economics also comes into play, Gilmore said.

Drug companies have slowed their own research into new antibiotics because it is more economical to focus efforts on drugs for long-term conditions, Gilmore said. Compared with statins, used for a lifetime by patients to control high cholesterol, a new antibiotic makes less economic sense. Such a drug has similar development costs but will be used just for a few weeks until a patient is cured. A replacement for last-line drugs like VRSA, used only in the most intractable cases, would bring in even less money.

That’s why, Gilmore said, it’s important that academic scientists do a lot of the groundwork and initial discovery no longer being done by pharmaceutical companies.

For Losick, that means collaborating with Kolter in working on biofilms to find new ways to fight a physical structure that appears to protect the bacteria from antibiotics. When bacteria form biofilms, Losick said, they become more resistant to antibiotics, so research into how to prevent biofilms from forming or how to disperse them can provide an alternative way to fight bacteria. Today, Losick said, if a biofilm forms on an implant, like a hip replacement, there are few good ways to fight it, and the implant often has to come out.

“Staphylococcus aureus is an important public health threat. The idea is to develop fresh strategies for controlling it,” Losick said. “I think we all feel very pleased on how the program is progressing.”