Audio engineers work in Harvard’s Audio Preservation Studio with its tape decks, turntables, and computers. Media technician Darron Burke (left) and David Ackerman (right), who directs Harvard’s high-tech audio studio, have digitized field recordings made in the 1930s on aluminum discs.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard’s best listeners

Lab conserves audible treasures

One Monday afternoon in 1958 a 17-year-old folk singer from Boston University auditioned at a jazz club on Mt. Auburn Street. There was no one in the audience but the club’s managers. They were skeptical. Why change the music card? Then their tryout started singing.

The girl was Joan Baez. The venue was Club 47. Soon, both were famous. Folk got one night a week, then it got the whole week at the coffeehouse down the street from the Harvard Lampoon. The little audition in Cambridge 54 years ago was a pivotal moment in the revival of American folk music. It also marked the start of a musical age that provided a soundtrack to the tumult of the 1960s.

No one recorded the young Baez that Monday afternoon, or her first official performance at Club 47 soon after. (She earned $10. Eight people were in the audience.) But about 30 reel-to-reel tapes exist from the early years of Club 47, which was open from 1958 to 1968. The recordings went into storage, and since then very little of this rare music — more than 40 hours of it — has been heard. (Three songs from Baez and Bob Dylan, however, made a first-time appearance in “For the Love of the Music,” a documentary on Club 47 released in May.)

Starting in 2010, the old tapes were assessed, played, and digitized by Harvard’s Audio Preservation Studio. This small but lively operation, staffed by three audio engineers, is tucked away in a few rooms on Story Street. The Club 47 project, finished in May, took 18 months of work. The original tapes — and now the digital files — belong to the New England Folk Music Archives. The project, funded by the Grammy Foundation, guaranteed Harvard a digital copy of the originals. A commercial release may happen. But the real winner is history.

“Ultimate preservation is making a loss-less copy,” said David Ackerman, a former rock guitarist who directs Harvard’s high-tech audio studio. That is: No information is lost in making a digital copy. (It’s different than remastering, a commercial art intended to clean up old recordings, not preserve them.) Just 15 years ago loss-less copies were not possible, said Ackerman. Analog copies of analog recordings inevitably come with signal degradation and inherent noise.

Ackerman and his audio team — Bruce Gordon and Darron Burke — are Harvard’s best listeners. Ackerman was hired in 1997 as the sole audio engineer at the Archive of World Music Collection at the Loeb Music Library. Later, he and Gordon were instrumental in establishing best practices for audio archivists. (The Harvard-Indiana University Sound Directions project, summarized in a 2005 report, is an industry standard.) Today, Ackerman and his staffers are active in the Audio Engineering Society, the Association for Recorded Sound Collections, and the International Association of Sound and Audiovisual Archives, where Gordon is a vice president.

The 15-year-old studio is a service provider for the University. Its mission is making true and complete digital copies of Harvard’s audio holdings. (Such holdings are vast, though only about 8,800 audio and audiovisual items have been identified so far. A survey started in 2010 by the Weissman Preservation Center is still under way.)

Video may one day be digitized at the Story Street studio, said Ackerman. But for now the focus is on making high-end digital copies of audio artifacts, some of them in fragile or rare formats. (In Harvard collections the oldest audio format is the wax cylinder. Ackerman’s studio has not dealt with that yet.)

The studio uses broadcast wave format, the high-resolution audio preservation format used worldwide.

But digitizing sound remains technically challenging. For one, some formats are very old. The audio studio has digitized field recordings made in the 1930s on aluminum discs. Operators could record only a few minutes of sound at a time, using phonographs that embossed sound-capturing grooves directly on the soft metal. Modern playback requires a custom fiber stylus. (Original field audio in Harvard’s Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature is in this fragile old format.)

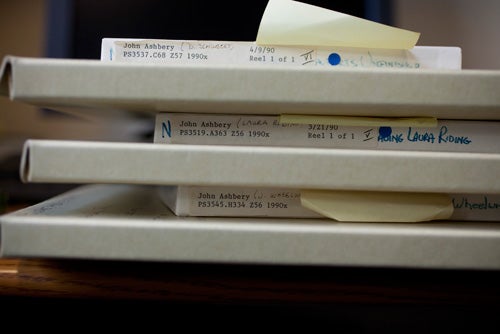

But most of the studio’s work involves old 78s, reel-to-reel tapes, LPs, and cassette recordings. A recent visit to an outer office revealed stacks, shelves, and boxes of recordings ready to be digitized. There were samples from sessions with writers Robert Lowell, Anne Sexton, Robert Frost, and Jack Kerouac. “Here’s Norman Mailer, 1976,” someone said, holding up a box. Not long ago the studio digitized audio from the Julia Child archives at the Schlesinger Library, including interviews, LPs, and radio promos. “The library is a living organism,” said Ackerman of Harvard collections, “always taking in new material.”

Even familiar technologies such as LPs and cassettes involve a confounding menu of formats, materials, and technical variants. The studio’s turntables for recording old 78s include a microscope for assessing groove width, a factor that was not standardized until the age of LPs. To add complexity, 78s were all made differently, with cores of paper, aluminum, or glass.

Reel-to-reel tapes — simple as they may seem — also present a range of problems, which have to be understood from the time recordings are unboxed at the studio. Ackerman and his fellow audio engineers look for dirt, mold, and loosely packed tape. They watch for “spoking” (when tape tension is not uniform) and “cupping,” the telltale curve of old tapes. They also look for what a tape is made of. It may be PVC, acetate, polyester, or even paper.

To start the digitizing process, technicians set the angle of the tape machine head — its azimuth — to the same angle used during the original recording. Then 1970s-era Ampex tape machines are calibrated so magnetic information can be read accurately. Once a tape is rolling, signals stream into two computers. One analyzes frequency and other sound variables in real time, filling the screen with spiked and bulbous patterns that bend, waver, and wiggle. The other makes a digital capture. “It might play in one go,” said Ackerman of recording an original. “But a lot of time it doesn’t.”

When it doesn’t, decades of audio experience come into play. Burke, 46, mentions his mother’s work in radio, and remembers live-recording “all the bands I wanted to be in.” Gordon, 58, blames his father and grandmother for his path to sound engineering. Both collected 78s, and played some of them on phonographs made before the Great Depression by the Victor Talking Machine Company. “Anybody can press play and record,” said Ackerman, 44. But the true audio business of equalization curves, RTA software, frequency, spectrum, Bext chunks, and authoring formats? That’s not so easy. It’s a realm for experts.

Every digitized recording at the studio includes “metadata,” embedded information about how the recordings were done and where they came from. It gives digitized archival copies the technical depth and provenance that scholars of the future will need. During the Club 47 project, the studio had a big “data” advantage: club co-founder Betsy Siggins. Her shouts from the audience 50 years ago — and some of her backup vocals — punctuate the old recordings. She can say the magic words: I was there.

Siggins, along with folklorist Millie Rahn — both now at the New England Folk Music Archives — visited the studio to identify songs and performers. The reel-to-reel tapes they brought are an untapped Who’s Who of music legends, including Baez (recorded twice in 1959), Jim Kweskin, Taj Mahal, Maria Muldaur, Tom Rush, Doc Watson, and Eric Von Schmidt.

In one song, complete with audience noise and chair-scraping, Bob Dylan plays harmonica and sings backup vocals. In another, when he finishes a song of his own, three people clap, but not hard. In a third, Dylan is introduced as a singer “from somewhere out in the Midwest.” Then he proceeds to wow the audience with “Talkin’ World War III Blues,” taking command of the mike, his instruments, and the audience like a pro. It’s like witnessing a birth.

“When I can’t sing ’em too good,” the young Dylan told the hooting crowd in 1961, “I sing talkin’ ones.” Then he snickered.

You won’t find unscripted moments like this on a studio track, in liner notes, or in a music review. Burke — who did most of the audio work in the Club 47 project — remembered picking up a cardboard tape box with “Dylan” scrawled on it in grease pencil. The tape had not been played in five decades.

“After the distortion and the wild level of the group before,” said Burke, “the recording level is perfect. His voice is clear. His guitar is even, confident, lyrical.” Dylan was barely 20 years old. He is 71 now.

The passage of all that time and the preservation of the lost recordings are a reminder of what the audio studio cares most about saving, said Ackerman: “things that don’t exist anywhere else.”

Share this article