Jennifer Weintraub (left), digital archivist/librarian, and Jane Kamensky, Schlesinger Library director, view a selection of items from the Blackwell collection before they are installed in the new exhibit.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

A family of common zeal

Radcliffe exhibit shines light on reform-minded Blackwells

Of the many items in a new Radcliffe exhibit devoted to a family of social reformers, one in particular points to the attitudes and assumptions they repeatedly overcame.

It’s a brief, age-weathered letter from November 1869, in which Charles Darwin thanks the author and activist Antoinette Brown Blackwell for sending him a copy of her recently published book “Studies in General Science.”

The note begins “Dear Sir.”

By then, Brown Blackwell was likely unfazed by the mix-up. In 1850, when Oberlin College refused to grant her a theological degree, she persevered to become, two years later, the first woman ordained as a Protestant minister in the United States. She went on to a career as a writer for The New York Herald Tribune, and became an outspoken women’s rights advocate and abolitionist. She also gave birth to five daughters, despite strong encouragement from a friend to draw the line at two.

“Not another baby is my peremptory command,” wrote the leading feminist Susan B. Anthony in a letter from 1858 that is included in the show.

Fierce devotion to reform and equality is the dominant theme running through “Women of the Blackwell Family: Resilience and Change.” The Schlesinger Library exhibit highlights the lives of seven Blackwell women, a group involved in key 19th- and 20th-century social movements around abolition, prohibition, health care, women’s suffrage, temperance, and education.

“They’re professional reformers in a variety of ways,” said Jane Kamensky, the library’s Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation Director, adding that there’s not much in “reform culture that they don’t touch on in some way.”

Only a small selection of the nearly 190,000 items contained in the Schlesinger’s five Blackwell Family Collections, whose correspondence, diaries, photographs, and writings were recently digitized with a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, are on display, but the selected material suffices to paint a vivid family portrait.

The story begins with Samuel Blackwell, an anti-slavery activist whose commitment to social reform was reflected in his business. Blackwell pursued methods of sugar refining based on beets rather than sugar cane since the use of cane relied on slave labor. In one exhibit case a lock of his hair rests near an anti-slavery manifesto he authored in the decade before his death. After he died, in 1838, the work of raising their nine children fell to his wife, Hannah, who imparted to them her strong moral beliefs.

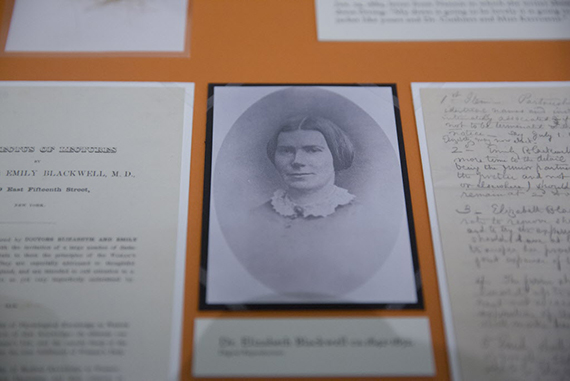

The eldest child, Anna, became a devoted Spiritualist, writer, poet, teacher, and journalist. Anna’s sister Elizabeth is perhaps the most prominent member of the Blackwell clan. In 1849, Elizabeth became the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States when she matriculated from Hobart College, then Geneva Medical College, in upstate New York. Eager to help other women succeed in the field, she and her sister Emily, the third female doctor in the country, founded the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children in 1857 as both a hospital for the poor and a training facility for female doctors and nursing students. In 1868 they opened the first medical college for women in the United States. In the display case devoted to Emily, a photo of the medical college’s class of 1887 shows eight students.

Though none of the Blackwell daughters married, the sons, Samuel and Henry, wed Oberlin classmates Lucy Stone and Antoinette Brown, who as staunch women’s right activists themselves fit right in with the family.

Stone was so opposed to restrictions placed on women in traditional 19th-century marriages that she and Samuel read and signed a wedding protest (a copy of which is included in the show) during their ceremony. It reads in part that they opposed “the whole system by which ‘the legal existence of the wife is suspended during marriage.’”

In a further break from tradition, Stone kept her maiden name. Women who followed her lead became known as “Lucy Stoners.” Stone’s reformist tendencies even extended to her attire. A sleeve of her black bloomer gown, a less-restrictive garment for women introduced in the 1850s that consisted of a knee-length dress worn over long, loose-fitting trousers, is part of the exhibit.

“It’s a whole stew of intertwined movements,” said Kamensky. “Women are not only politically deformed, but deformed by corsets and wide skirts.”

“Women of the Blackwell Family: Resilience and Change” is on view at the Schlesinger Library through Oct. 21.