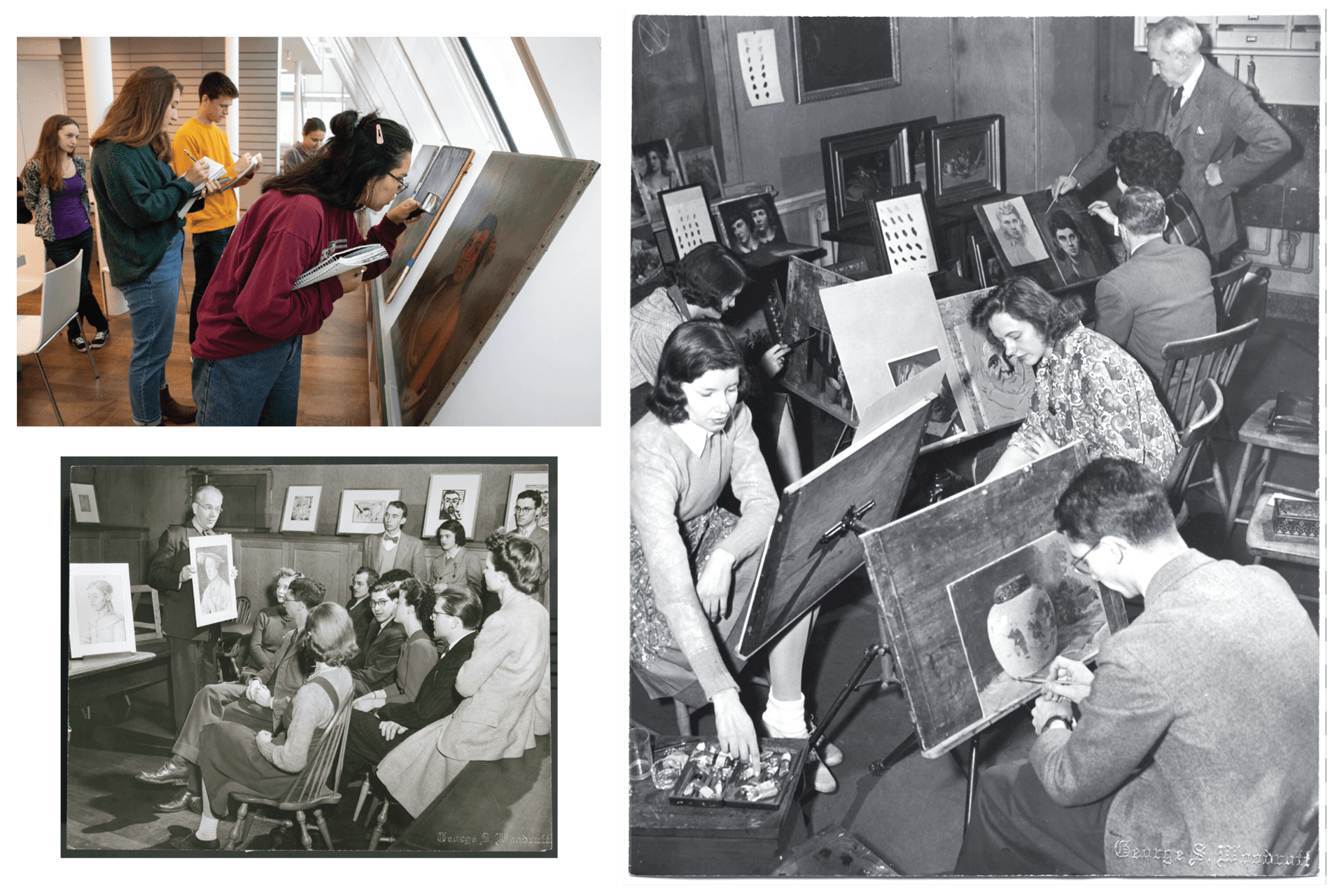

Harvard art history students through the years.

Harvard file photo; Harvard Art Museums Archives

Educating the eye

Harvard celebrates 150th anniversary of art history department, the nation’s first

In 1873, Charles Eliot Norton wrote a letter to his cousin, Harvard President Charles William Eliot, to propose what was then a bold idea: add art history courses to the University’s curriculum.

Education, Norton argued, is incomplete without the study of the fine arts. Norton, who had just returned from five years in Europe, had become inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement after hearing art historian John Ruskin lecture at Oxford and conversing with his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson on the boat back to Boston.

“Architecture, sculpture, and painting have been, next to literature, the most important modes of expression of the sentiments, beliefs and opinions of men,” Norton wrote. “They afford evidence, often in a more striking and direct manner than literature itself, of the moral temper and intellectual culture of the various races by whom they have been practiced and thus become the most effective aids to the proper understanding of history.”

His argument was convincing. Thus began Harvard’s Department of History of Art and Architecture (originally called the Fine Arts Department), making Harvard the first U.S. university to develop a professorship and a permanent program for art history curriculum. This year the department will mark its 150th anniversary with a conference slated for Nov. 7-8 called “The Education of the Eyes: 150 Years of Art History at Harvard.”

Co-hosted by the Harvard Art Museums, the conference will bring together academics, art critics, and curators from across the U.S. and Europe to reflect on the history and legacy of the department, and on the future of the art history field. Speakers include former Museum of Modern Art Director Glenn Lowry, art critic Rosalind Krauss, art historian Svetlana Alpers, and New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman.

The conference comes at a time “in which the visual has more importance than ever in the production of culture,” says Felipe Pereda, director of graduate studies for the department.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

“I’m so thrilled and happy about the conference that is going to happen,” said Felipe Pereda, Fernando Zóbel de Ayala Professor of Spanish Art and director of graduate studies for the department. “For the graduate students, it presents what the future could be and gives them the opportunity to think about how they can shape where the department is moving to, and where art history is moving to, at a moment in which the visual has more importance than ever in the production of culture.”

The conference will include presentations on topics ranging from the relationship between artist and critic, to art that is included versus excluded in the discipline. Pereda, who has been the driving force behind planning the conference, conducted extensive research to piece together the department’s origin story, with documents found in the archives at the Harvard Art Museums, Houghton Library, the University Archives, and University of London’s Warburg Institute.

The event’s title comes from an idea central to an early ethos of Harvard’s Fine Arts Department: the German concept of Augenerziehung, which translates to “education of the eye.”

“The idea that developed was that to be educated wasn’t only going to be in the realm of reading books and reasoning from them. There was something different and deeply salient about grappling with artifacts, with humanly made things,” explained Joseph Koerner, chair of the department and Victor S. Thomas Professor of the History of Art and Architecture.

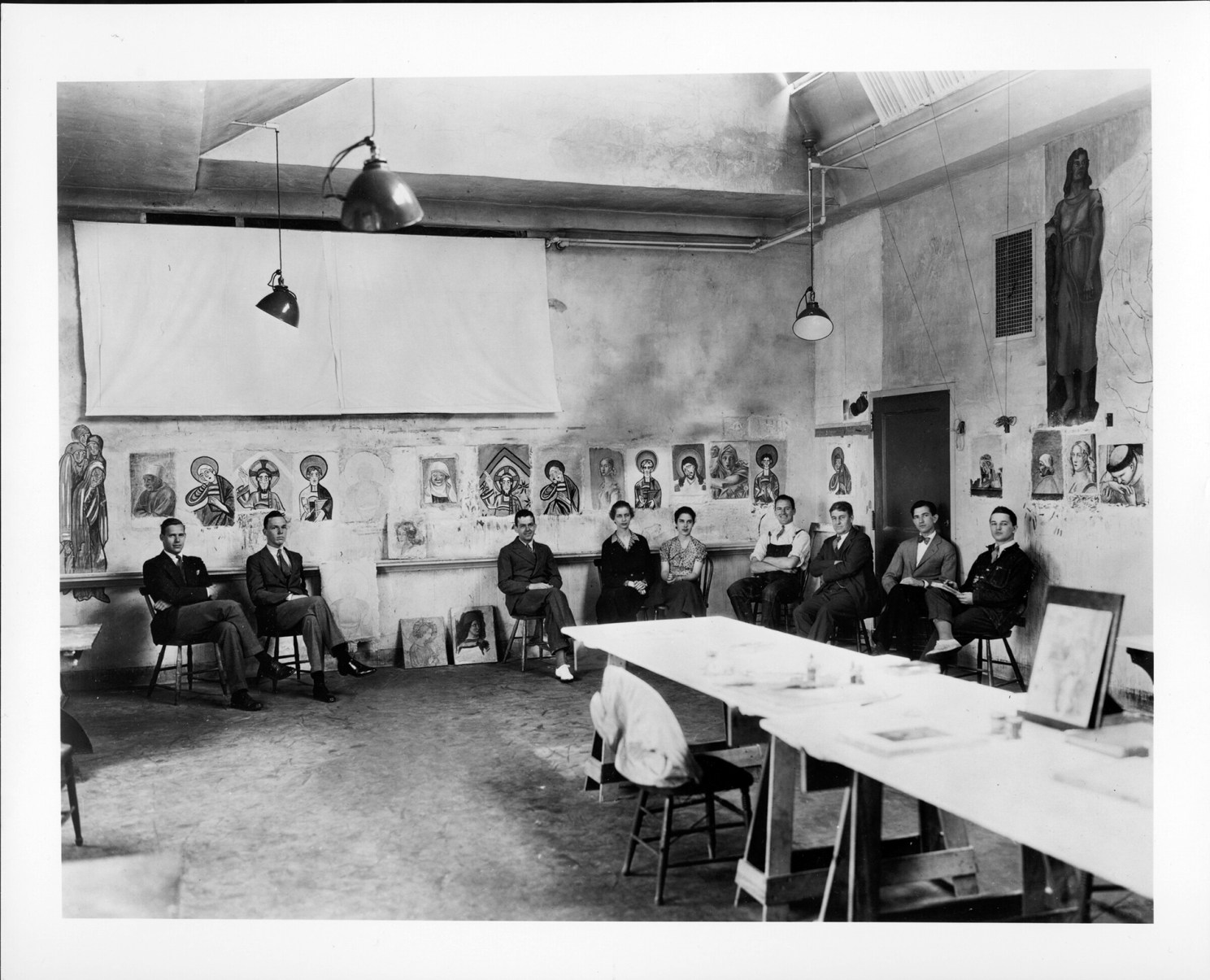

An art course takes place inside the Fogg Museum in 1932, back when the curriculum was more hands-on and less “bookish.”

Harvard Art Museums Archives (unless otherwise noted)

Students take notes in Warburg Hall.

When Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” came to Harvard in 1941, students had the opportunity to study it up close.

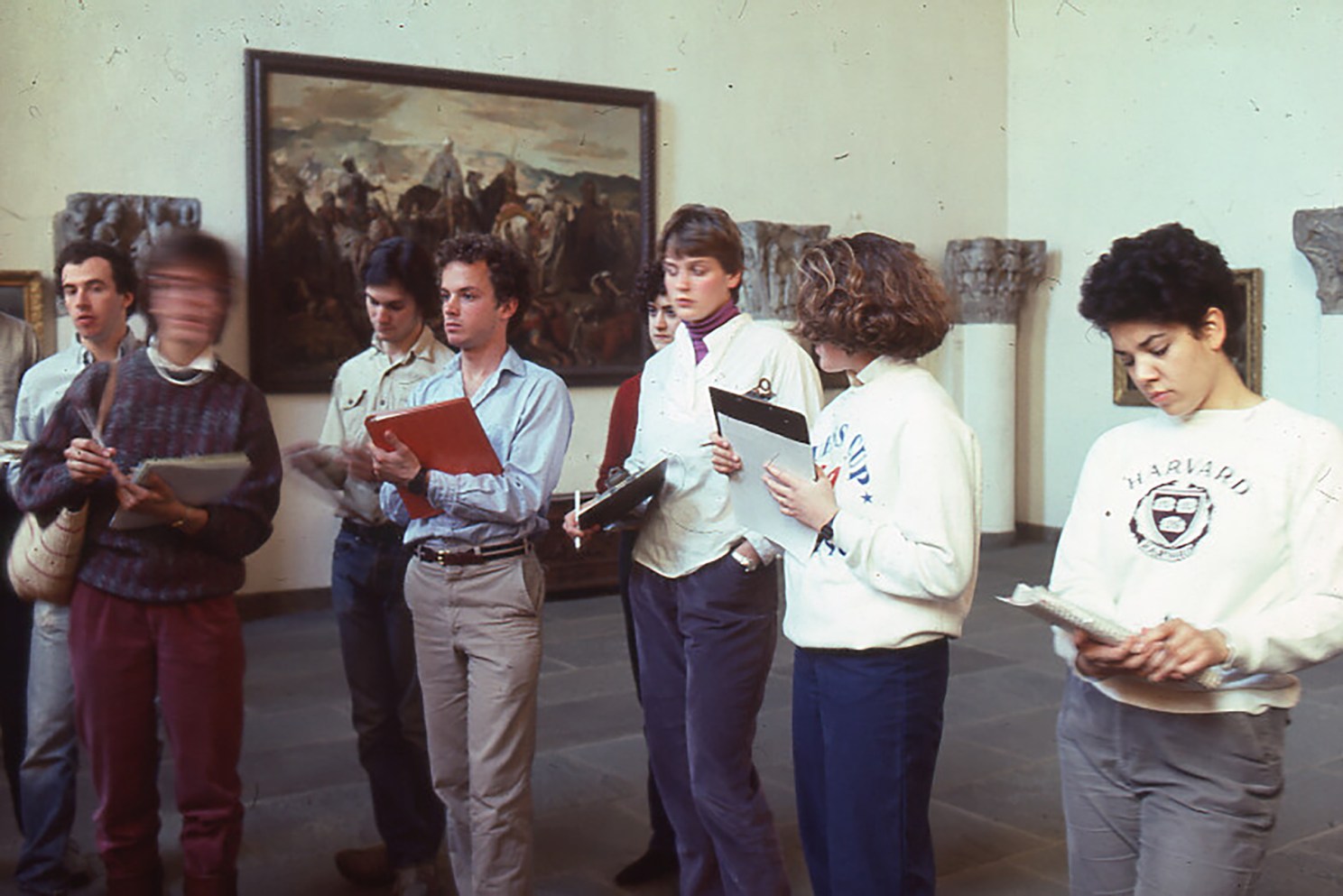

Students engage with David Smith’s “Fish” in 1981.

© The Estate of David Smith

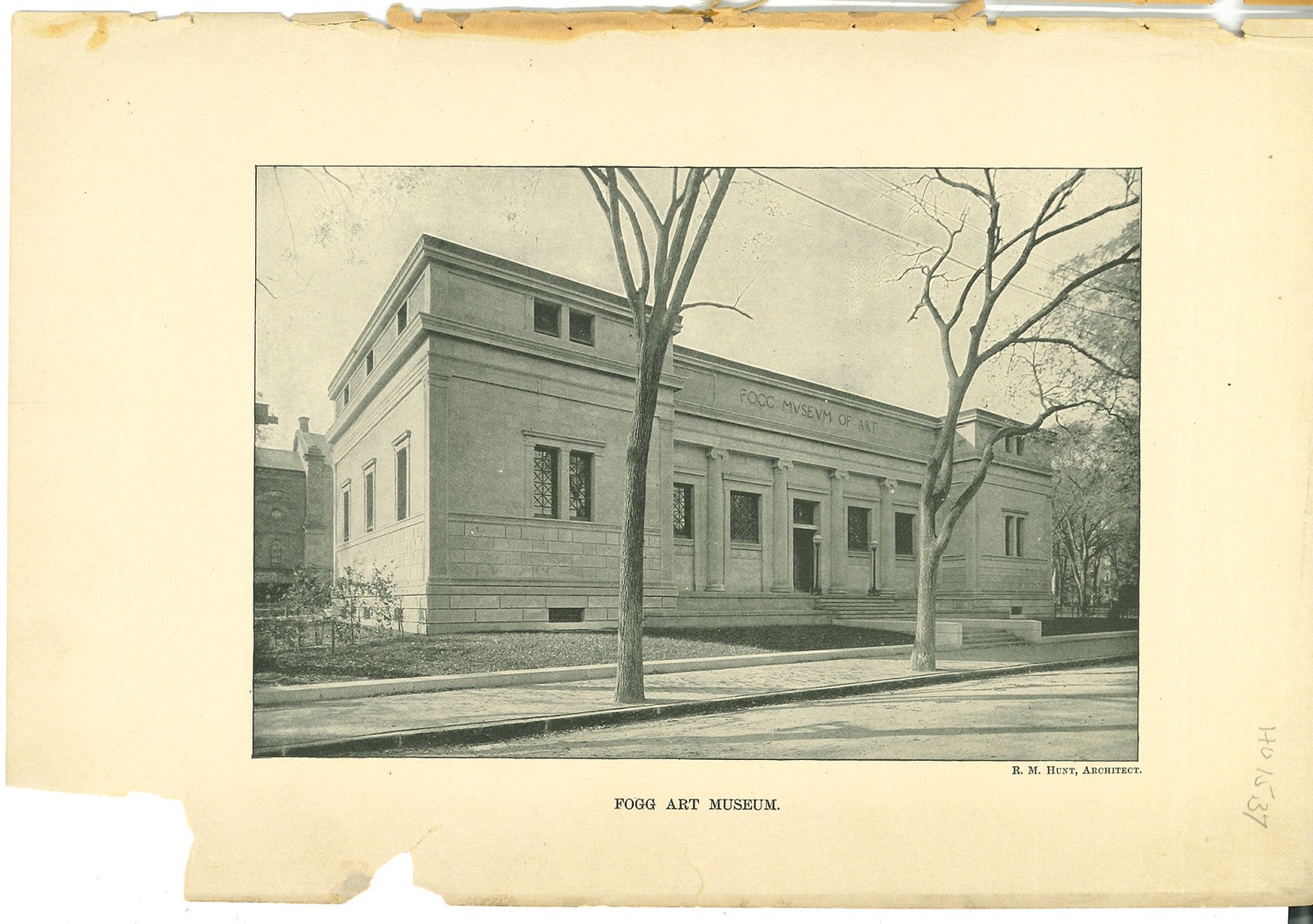

Hunt Hall, which housed the original Fine Arts Department and the Fogg Museum from 1895 to 1925. The building was demolished in 1973.

Harvard University Archives

From the start, the new department was designed to combine intellectual inquiry with practical training. The first two fine arts courses offered, in the 1874-75 school year, were “The History of the Fine Arts and Their Relation to Literature,” taught by Norton, and “Principles of Design,” a studio course taught by painter Charles Herbert Moore, in which students learned to draw.

“The program initiated students in the practice of drawing — not to become artists, but to understand artists’ creative process. In other words, to educate their eyes,” Pereda said.

This commitment to studying real objects led the University to begin collecting art. In 1895, Harvard founded the Fogg Museum of Art, making its Art History Department the first in the nation to have its own museum. Housed with the Fine Arts Department in Hunt Hall, which was located where Canaday Hall is today, the museum served as a “laboratory for the eye,” where classes often gathered to examine paintings up close.

“It was a laboratory,” Koerner said. “There were instruments, and people studied how paints were made, how lacquer is produced, how bronze was cast. Science and art history, they’re not that different, both are ways of understanding how things came about, how facts are produced.”

“It was not just about learning the difference between a Rembrandt and one of his followers, or about appreciating beautiful things.”

Joseph Koerner, department chair

Over time, the emphasis on practicing artmaking dwindled as the field became more “bookish,” Koerner said. The art history department stopped offering drawing courses in the 1960s. By the time Koerner was completing his graduate work and beginning to teach in the 1980s, it was “inconceivable” that a scholar might try learning skills like etching, engraving, or ink-making as part of the research process, he recalled.

But now, those ideas are coming back around.

“Fast-forward to today, the thoughts of 150 years ago seem to me to align again with what people now think the study of art should about: understanding how material objects are made by learning the processes by which they were made and by looking very carefully, using whatever methods best suit your object,” Koerner said. “That’s what a lot of the younger art historians are doing, even to the point of apprenticing themselves to weavers and printmakers.”

Koerner added that training the eye is even more important today, as visual images impact how we understand politics, especially in the new era of AI-produced images and digital falsification. Many HAA courses today, such as “A Colloquium in the Visual Arts,” have “looking labs,” opportunities for classes to go to the Harvard Art Museums to examine objects and discuss them.

Both Pereda and Koerner hope the conference will serve to “rekindle” the close relationship between the department and the Harvard Art Museums and provide a space to celebrate and critically examine the field and its history.

“It’s inspiring to see that 150 years ago, people conceived of a future history of art in such a deep, foundational way,” Koerner said. “It was not just about learning the difference between a Rembrandt and one of his followers, or about appreciating beautiful things. It was really about what education should be ideally; about what it means, say, for undergraduates to learn to look closely at artworks and so do with advanced research ongoing at the University.”