Is the secret to immortality in our DNA?

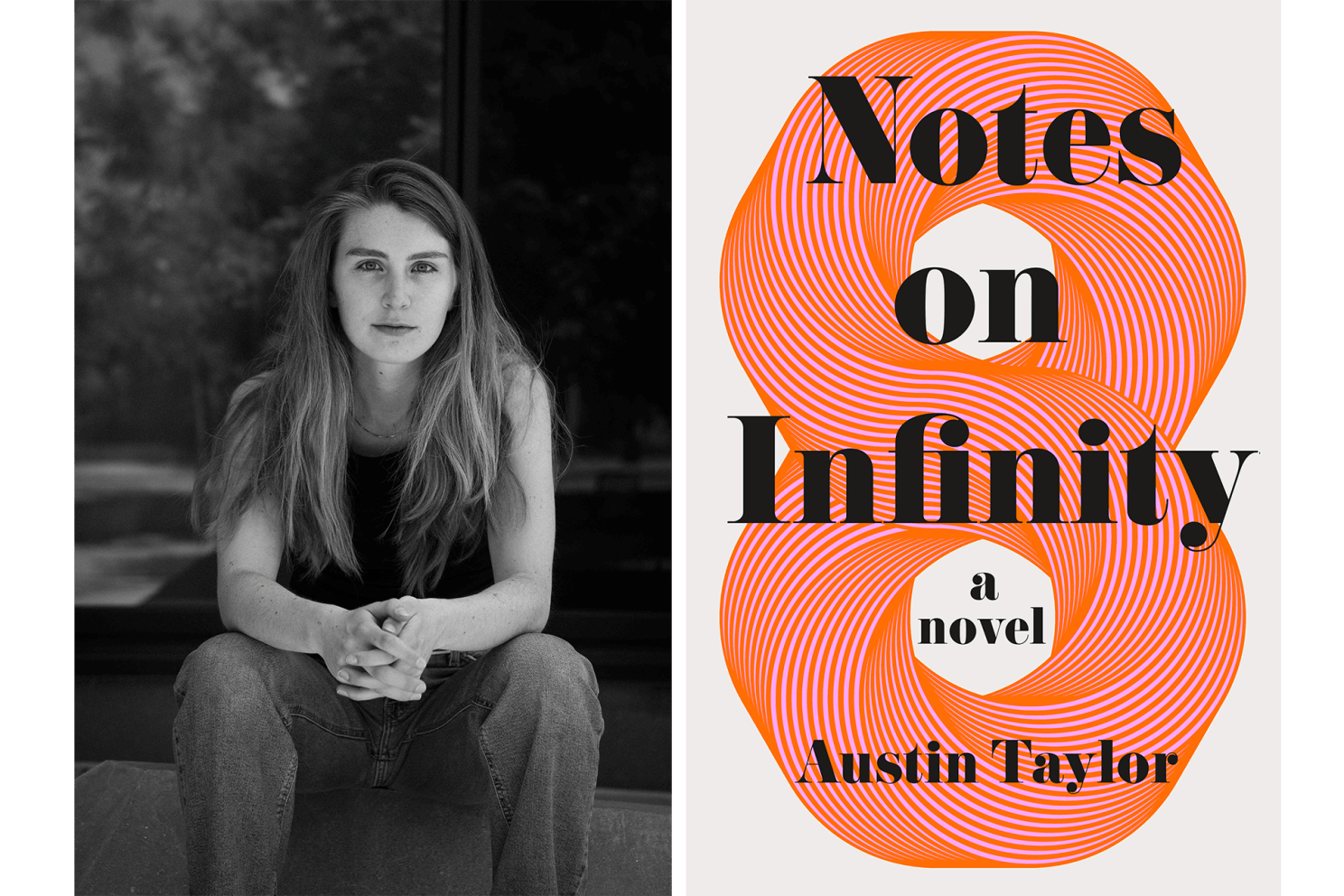

Photo by Maryam Hiradfar

Alum’s campus novel offers cautionary tale to biotech culture

It’s your typical biotech love story: A couple of eager Harvard students stumble upon a brilliant scientific breakthrough in anti-aging, drop out of school to pursue their dream, experience a fast and furious rise to fame before … well, we won’t give the ending away. In “Notes on Infinity,” Austin Taylor ’21 showcases her grasp of science and love of literature. During her own time at the College, she double concentrated in English and chemistry, a decision that has served her well in writing her debut novel. The Gazette spoke with her about how her time at Harvard influenced her writing, as well as what’s next in her career. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In the book, Harvard students Zoe and Jack discover a new way to unlock the potential of anti-aging. You draw from many studies and chemistry principles. Does the science track? Does the secret to immortality lie in our DNA?

My first disclaimer is that while I studied chemistry, it was physical chemistry and not bio. However, it was important that I get the scientific context right. I wanted the novel to be completely plausible, so everything leading up to the actual work of the two main characters is real and I tried to communicate it accurately. So is it possible that a discovery like the one they made could be made? I think theoretically, yes. Has a similar discovery been made? No.

David Sinclair is doing some work on this. And the main discovery that they work from is the Yamanaka factors, which allow us to turn back the clock on aged cells. So if we figured out how to turn back the clock on aged cells for many cells in our body at one time, one would think that would have an anti-aging effect. But that’s the part where the science becomes fiction.

You’ve said that one theme you wanted to explore with this novel was empathy. Why is that?

One of the things that inspired the book was the many startup scandals in the news. As I followed those stories, I was struck by the simplicity of the punchy, dramatic, six-word headlines. It’s very easy to forget that those headlines are describing real people who had whole lives leading up to a set of decisions, a set of moments that resulted in these headlines being published. I don’t think that’s a good thing; I think it’s really important not to flatten people. It’s important to humanize others, and I think that the most important task of fiction — both for writers and for readers — is to produce empathy.

“When you dump extreme amounts of money on people who have good ideas, and you encourage them to ‘move fast and break things,’ the incentive structure you create is not always one that will produce good, sound science.”

How did your own experiences inform the characters in this novel?

One of the main characters, Zoe, is a young woman in STEM. I studied chemistry, so I also was a young woman in STEM. Some of the tension she experiences is the feeling of tokenization or of being perceived primarily by or through the lens of her gender. Zoe struggles throughout the book with very much just wanting to be a scientist, but feeling like she’s constantly the woman scientist, especially because she starts a biotech company. She is lauded for being a woman founder, which in some ways is great, but in other ways is very isolating and frustrating.

I certainly did not drop out and form a billion-dollar startup, but I did find myself wondering if I was being given opportunities in the sciences because I was working hard and doing good, interesting work — or if I was being given opportunities because I was a woman and a minority in the field. That is a tough feeling that a lot of minorities in various spaces experience, and it can create a lot of tension and insecurity.

You also tackled what seems to be a recurring theme in biotech start-up culture, with the often quick rise to success followed by failure. What were you attempting to explore there?

Two major scandals that happened just before and during the writing process were the rise and fall of Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes and the collapse of FTX, the cryptocurrency exchange founded by Sam Bankman-Fried. When you put people in a high-pressure, high-stakes environment, they can behave differently than they maybe would otherwise. For the two main characters, those two environments are first Harvard College — which is very high-pressure and very high-stakes — and then the venture-capital-funded world of biotech. When you dump extreme amounts of money on people who have good ideas, and you encourage them to “move fast and break things,” the incentive structure you create is not always one that will produce good, sound science.

Chemistry and English make a unique pairing. How did concentrating in both affect your professional pursuits?

As an undergraduate, I was really excited about science. I also really loved my English classes. I remember my sophomore year when I was thinking about declaring, I nervously soft-pitched the idea to my chemistry adviser of a joint concentration, thinking he was going to say it was a silly idea. Instead, he was very excited about it. I remember walking out of that meeting feeling thrilled that it was a possibility. I had a fantastic time pursuing the two, and the combination is sort of perfect for the novel, right? I leveraged my scientific literacy during research. I drew a lot on my experiences as a chemistry student and in the lab, as well as the skills in writing and reading that I developed as an English concentrator.

Were there any faculty who were particularly helpful to you?

My advisers in the Chemistry and English departments, Greg Tucci and Daniel Donaghue, were incredibly supportive of my joint pursuit. I also took two classes in the English department — contemporary fiction and a creative writing course with Jill Abramson — that were formative for me as a writer. Jill gave me some very generous feedback and was very supportive; it was the first time that I really considered that writing could be a career for me. My Principal Investigator, Cynthia Friend, was also a great mentor and is a fabulous scientist.

And then, broadly speaking, the faculty, staff, and peers that I was surrounded by at Harvard were just brilliant and doing incredible things. It was intimidating and challenging, especially for the first few years, but being in that environment made me an immeasurably better thinker, writer, problem-solver, friend, and person. I’m deeply grateful to everyone who made up the community during the time that I was there.

What’s next for you?

I’ll be attending law school at Stanford University in the fall. I’m interested in the interface between emerging science and tech and the law. While I was writing my first novel, Chat GPT emerged, and so my legal and professional interests in the publishing space sort of dovetailed. I’m hoping to work on AI governance, particularly as it relates to art and media.

I don’t have any plans to stop writing, so I’m hoping to pursue some sort of career as an attorney or legal scholar in parallel with a career as a novelist. I’m working on my second novel currently and hope to keep writing for as long as people are interested in reading what I write.