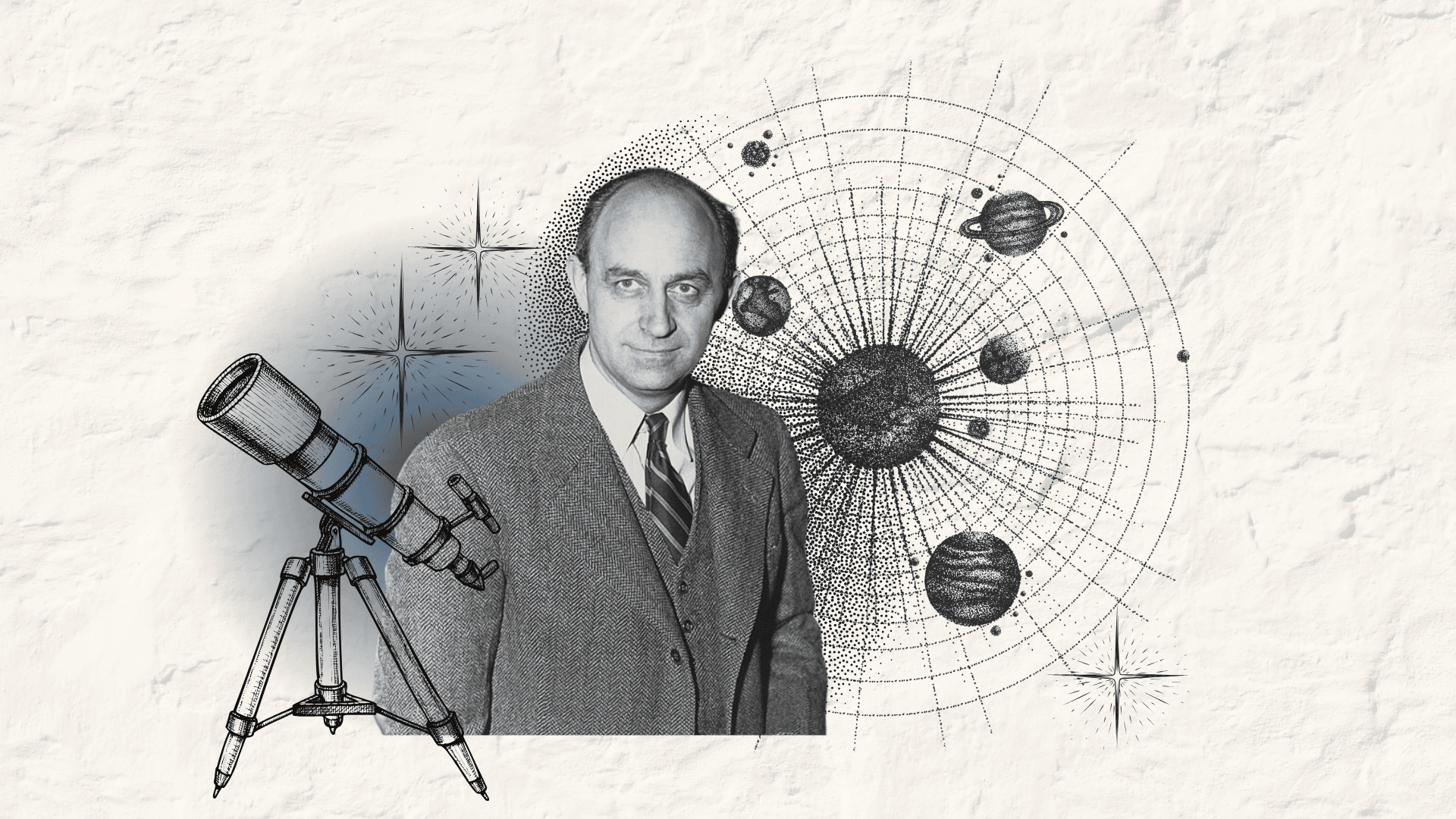

Enrico Fermi.

Photo illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Still waiting

75 years after Fermi’s paradox, are we any closer to finding alien life?

It was a simple question asked over lunch in 1950. Enrico Fermi, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist who helped usher in the atomic age, was dining with colleagues at Los Alamos, New Mexico, when the conversation turned to extraterrestrial life. Given the vastness of the universe and the statistical likelihood of other intelligent civilizations, Fermi wondered, “Where is everybody?”

Seventy-five years later, David Charbonneau, a professor of astronomy at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, says we’re closer to an answer.

When Fermi posed his famous paradox, Charbonneau said, we hadn’t identified a single planet beyond our solar system. The 1995 discovery of the first exoplanet allowed scientists to break the paradox into smaller, more solvable questions: How many stars are there? How many of those stars have planets? What fraction of those planets are Earth-like? What fraction of Earth-like planets support life? And finally, what fraction of that life is intelligent?

“We have made tremendous progress on those questions,” said Charbonneau, who co-chaired the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s 2018 Committee on Exoplanet Science Strategy. “We now know that one in every four stars, at least, has a planet that is the same size as the Earth and is rocky, and is the same temperature as the Earth, so it’s what we would call a habitable-zone planet. Those are very secure conclusions.”

The next step is identifying biosignatures — chemicals in a planet’s atmosphere that could only be there because of biological processes. Charbonneau says that the necessary evidence faces a major technological hurdle: It requires far more data than our current instruments can provide.

Recognizing that challenge, the National Academies’ Committee for a Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics 2020, on which Charbonneau served as a panel member, recommended the development of the Habitable Worlds Observatory, a space telescope designed to hunt for chemical signs of life on other planets. The HWO, if it were built and launched, would image at least 25 potentially habitable worlds. The project remains tentative.

There’s still the question of just how common life, let alone intelligent life, really is. It’s possible, Charbonneau said, that if you take any habitable-zone planet, add water, oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphorus, and give it about a billion years, life will develop. Or you could have those very same conditions, and it would all remain stubbornly lifeless. You only have to look at the first habitable planet to have a much better idea how common life is.

“If you look at the first one and there isn’t life, you’ve already learned, from a statistical perspective, that it’s not a guarantee that life forms. And then you have to think logarithmically. You have to think, maybe it’s one in 1,000 or maybe it’s one in a billion, or maybe it’s one in a trillion. And all those possibilities basically would mean there’s no life that we can interact with.”

Avi Loeb, Frank B. Baird Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard, says the search for extraterrestrial life should expand beyond traditional approaches. Loeb is the founder of the Galileo Project, which studies both unidentified aerial phenomena spotted here on Earth and physical objects that may have come from other solar systems.

The project is named for the Italian astronomer who was persecuted in the 17th century for arguing the Copernican theory that the Earth was not the center of the universe. Proof of billions of habitable planets in our galaxy alone is a reminder that we’re not as unique as we think we are, Loeb says. “The message from nature is, don’t be presumptuous, you are not privileged.”

Avi Loeb.

Harvard file photo

David Charbonneau.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Loeb made headlines in 2018 when he suggested that ‘Oumuamua, the first known interstellar object to pass through our solar system, could be an alien lightsail or debris from an extraterrestrial ship. Despite pushback against the idea, Loeb says we shouldn’t brush anomalies under the carpet: We should at least get the data to find out for certain. He thinks that Fermi was doing himself a disservice by wondering idly about whether there were aliens, like someone who complains of being lonely but won’t try to meet new people.

“It’s the most romantic question on Earth,” Loeb said. “Do we have a partner out there?”

For Charbonneau, the chances of finding that partner are slim. Even under ideal circumstances — if our nearest interstellar neighbor, Proxima Centauri, hosted intelligent life with radio technology — sending a single message back and forth once would take the better part of a decade.

There’s also the chance that the aliens are less interested in us than we are in them.

“If you look around on the Earth, there are a lot of organisms, some would say intelligent organisms, that are not interested in developing technology, and they’re also maybe not interested in communicating,” Charbonneau said. “We humans love to communicate, and we love to connect, and maybe that’s just not a property of life: Maybe that’s really a property of humans.”